Girlhood can be a hell of an optical illusion: when you’re living it, it’s just one day after the next. It’s only after you reach the other side that you’re able to look back and realize how the years between birth and young adulthood were often exercises in gender norms. Sometimes, these were as benign as being given a Barbie for your birthday when you want a Tonka Truck (or vice versa). Other times, these exercises in What Should Be Male and What Should Be Female—like being made to wear clothing that felt like a cage—seem violent in hindsight, and were frequently met with resistance that was dismissed by parents and guardians as a “temper tantrum.”

via fuckyoulizprince

Liz Prince‘s new graphic memoir Tomboy is a smart and outright cute exploration of girlhood by a girl who didn’t ‘fit’ but survived to tell the tale. The book follows a young Liz from the age of four to her mid-teens. While it ends with her finding her footing in a punk rock zinester feminist world, the follow-up to that is full of gender-related struggles, including:

- Being disgruntled with the frilly, pink, and conventionally feminine

- Getting teased for wearing boys’ clothing

- The revolving door of friendships otherwise known as girlhood

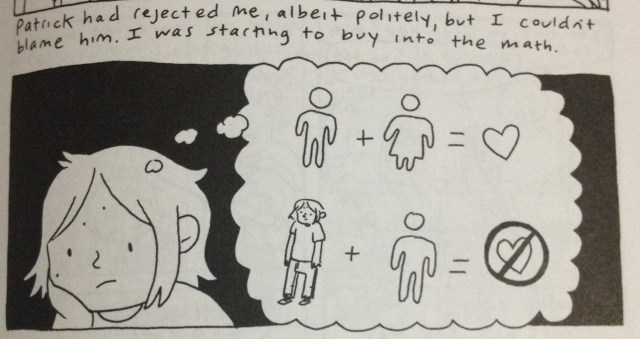

- Crushes

- Having a little brother

- Being too much of a boy to be friends with girls

- Being too much of a girl to be friends with boys

Tomboy mostly consists of your usual comic panels with the occasional journal-style entry thrown in, all of which narrate the life and times of a hyperactive-minded adolescent who can’t shake the fact that she’s just a smidge different from her female peers.

While reading Tomboy, I couldn’t stop thinking about the younger folks I know who could benefit from this book. That isn’t to say that Tomboy is a children’s book—it’s far from it, and I know plenty of adults who could learn approximately five things from this enjoyable, sermon-free memoir. But Tomboy offers such concise explanations for abstract, hard-to-grasp concepts like the difference between gender identity, gender presentation, and sexuality (things that it took yours truly several years of undergrad, a few years of sticking my foot in my mouth, and a fifth of Maker’s Mark to fully wrap my head around). One more person who gets how fucked the gender binary is because they’ve read Tomboy is one more person who 1.) either resists feeling quite so isolated in their gender identity or 2.) resists bullying those who, like Liz and her little brother, don’t quite ‘fit’ into one-size-fits-half gender roles. It’s important to fight relentlessly for the rights of the Fun Homes and Miseducation of Cameron Posts to exist on our public school shelves and syllabi, but books like Tomboy are just as important: because they’re relatively modest and resist political pigeonholing, they slip in unnoticed, reach an audience, and make just as much—if not more—of an impact.

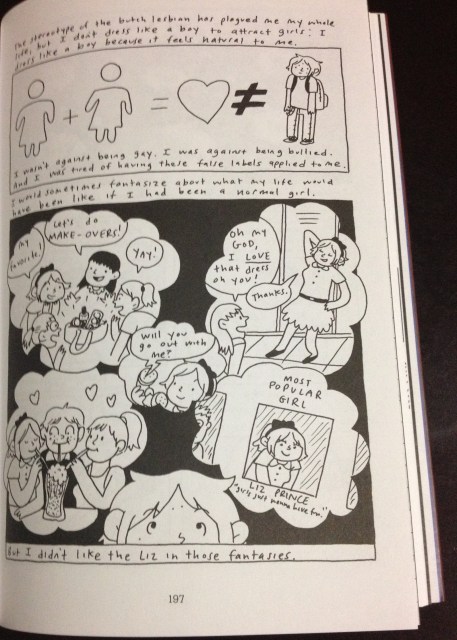

One of the two things I loved most about Tomboy is Prince’s depiction of the incentives for being a normal girl. Young Liz is constantly torn between her comfort in her own skin and what others expect from her. In one panel (pictured below), she fantasizes about the girl she could be if she played by the rules. The second thing—as odd as it may seem—is that young Liz identifies as straight. It’s no secret that girls are sexualized, and tomboys aren’t exempt from that: the gender deviancy is often seen as something one will grow out of when she becomes boy crazy, or an indicator that she’ll become a dyke. The honest reality is that some of us tomboys grow up to be gay women and some of us don’t; to use being a rough-and-tumble girl as an early sign of imminent lesbianism despite gender and sexuality being vastly different arenas is, well, just not true.

“I’ve worked hard to not engage the gay childhood narrative—I never talk about tomboyish behavior as an antecedent to my lesbian identity,” the late activist Leslie Feinberg wrote in 1998. “I don’t tell stories about cross-dressing or crushes on girls, and I intentionally fuck with the assumption of it by telling people how I used to be straight and have sex with boys like any sweet trashy rural girl and some of it was fun. I see these narratives as strategic, and I’ve always rejected the strategy that adopts some theory of innate sexuality.” Liz Prince’s Tomboy possesses the same subversiveness that Feinberg’s work does. Because of this, she’s able to show how a straight girl is affected by homophobia by simply rejecting aesthetic gender norms. It was refreshing to read a narrative where female masculinity was not a prequel for homosexuality; Tomboy reminded me to check myself the next time I catch myself sighing, “she’s such a dyke” over a cute celebrity in a snapback who doesn’t have a boyfriend.

I randomly found a little book of comics called “Will You Still Love Me If I Wet the Bed?” by Liz Prince in a comic book shop and was really impressed: so cute and funny and real and dorky.

“Tomboy” looks really awesome! Thanks for reminding me about it!

I was lucky enough to come across this gem at my local library and it is SO good. I wish that more people had access to stuff like this when I was younger, it seriously would’ve made life a lot easier.

It would’ve made me much more comfortable as a child to have read something like this, and I can’t even imagine what life would’ve been like if this was widely read by others. The “Being too much of a boy to be friends with girls. Being too much of a girl to be friends with boys” idea was painfully accurate for me from kindergarten to eighth grade, and if I had heard from anywhere that it was possible to be both androgynous and normal I would’ve been so much happier.

Same! <3

This looks really interesting – thanks for letting me know about it!

:)

I just downloaded Tomboy on my Kindle. I can’t wait to start reading!

I LOVE LIZ PRINCE. Tomboy was excellent and I highly recommend checking out her zines or online comics on her website. http://lizprincepower.com/art

Additionally, Ramsey Beyer is someone I follow the work of. You can read her first graphic novel online here: http://everydaypants.com/year-one/cover/

Noelle Stevenson is also one of my comic heroes. I live vicariously through these amazing cartoonists.