feature image photo credit Alejandro Alvarez/News2Share

The question that both the LGBT community and media outlets seem to be asking over and over again this summer is a variation on: is Pride a protest? Should it be? We all seem to agree that it was originally a protest, and then maybe a protest presented as a parade, and that now it’s mostly just a parade — we know that corporate involvement has changed Pride deeply, and while we don’t know how much LeAnn Rimes is pocketing for headlining PrideFest in New York City, we suspect it’s a lot. The New York Times asked if we’re going to “march in protest or dance our worries away;” Krista Burton wonders whether Pride is still for queer people like her if it’s also “yet another place that straight white people now feel 100 percent welcome.” The answer to what Pride was, is, and what it should be will always be answered by local LGBT communities, without which Pride does not exist (despite the fact that it has in its contemporary iteration become a party to which straight cis people and/or allies also feel some level of invitation and even ownership). This year, the answer many people in many cities gave is that Pride is something which itself needs to be protested, or at least protested at.

Since Pride month of 2016, there have been several major national conversations that have added new context to what were already points of tension around Pride events. There’s increased awareness of bank and corporate investment in the Dakota Access Pipeline and other projects that undermine the wellness and sovereignty of Native peoples. There’s an increased level of knowledge about and engagement in the relentless police violence against Black people in the US thanks largely to the work of Patrisse Cullors, Opal Tometi, and Alicia Garza, the Black queer women who founded Black Lives Matter. And there’s a turbulent national discourse around the role of police and how they are and aren’t accountable to the communities they’re meant to serve. All these have driven the urgency behind figuring out how the presence of banks, corporations, police, and other entities plays out at Pride. And of course, there’s the truth that many casually liberal or apolitical Pride attendees have experienced major shifts in how they perceive the politics of everyday spaces and encounters, and how they experience themselves and their communities as political entities, since the 2016 election. It’s never been possible for Pride to ever really be apolitical, but for a few years, it was maybe possible, for some people, to feel like it was.

In 2017, for a lot of reasons, affecting an apolitical stance isn’t remotely possible. The Trump administration has thrown us all for a desperate loop. Concerns about the growth of private prisons, deportation of undocumented immigrants and access to health care are more urgent than ever. The Trump administration is composed of and appeals to a racist, homophobic, transphobic, misogynistic “alt-right” who see LGBT folks and people of color as problems to be dealt with rather than fellow citizens. 14 trans women of color have already been murdered this year. The harmful systems that our diverse communities suffer under existed long before Trump, but they are laid bare and exacerbated right now in specific ways that can’t be ignored.

So the question is pushed to the forefront: what are the politics of Pride? Who and what are they centered around?

We’re seeing that question asked and answered in a few ways. In LA this year, the city’s official Pride became the Resist March, an event “in direct response to the current political climate and need to unite and fight against Trump and his administration.” The Resist March’s mission doesn’t organize around specific policy demands, but emphasizes coalition, stating “When any American’s rights are under threat, all our rights are threatened.” It’s not particularly concrete language, but it does position LGBT identities and other intersecting marginalized identities as being currently politicized and at risk, rather than Pride being conceptualized as an event which honors and memorializes past harm or injustice.

Instead of a Pride Parade meant to celebrate our past progress, we are going to march to ensure all our futures. Just as we did in 1970’s first LGBTQ+ Pride, we are going to march in unity with those who believe that America’s strength is its diversity. Not just LGBTQ+ people but all Americans and dreamers will be wrapped in the Rainbow Flag and our unique, diverse, intersectional voices will come together in one harmonized proclamation.

We #RESIST forces that would divide us.

We #RESIST those who would take our liberty.

We #RESIST homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, sexism, and racism.

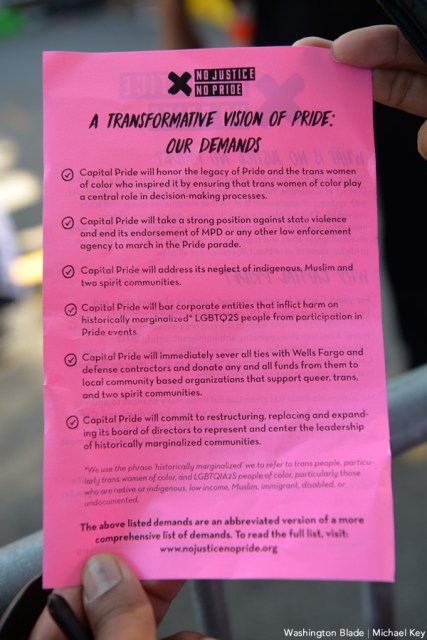

Other political actions centered around Pride — but not sanctioned by Pride itself — have been more specific in their calls for a more concrete articulation of the politics of Pride. Last weekend, DC group No Justice No Pride linked arms to block the parade route in order to draw attention to the LGBT movement’s “collusion with systems of oppression that further marginalize queer and trans individuals.” The Washington Post quotes the protesters as saying “Capital Pride organizers have cooperated too closely with police and corporations — institutions that marginalize minorities including immigrants, the queer and trans communities, and people of color.” The direct action was met with what seems like significant pushback from Pride attendees, with some shouting “Shame, shame,” and one person reportedly yelling “How dare you insinuate we’re racists.” The conflict of viewpoints on Pride is maybe best summed up in the man who the Washington Post quotes as saying, “I fought for 20 years for this, and now you’re going to ruin the parade.” Although the parade was rerouted, no one was arrested at DC’s Capital Pride in connection with the protest.

Local LGBT paper Washington Blade‘s coverage of the Capital Pride protests highlights similar divides in viewpoints; many expressed that the protest “did more harm than good,” “alienated the community and allies,” and some wondered why the organizers of No Justice No Pride hadn’t joined the organizing of Capital Pride to have input into the event directly. Others felt differently:

“It does seem to be predominantly the cisgender, white gay men who are the most upset these people weren’t dragged away and arrested,” said one long-time local black lesbian activist who is not allowed to speak on the record because of her job. “But D.C. has a long history of allowing protesters to exercise their First Amendment rights. We’re not going to drag people from the street so you can continue to party. That’s ridiculous. This is a backlash against the white gay men from Logan Circle. Did they want this to turn into the next Ferguson? Think a little bit about the pros and cons and check your privilege at the door.”

The Blade also reported inconsistencies in some accounts of the protest and parade, from differing accounts of how many groups were holding a No Justice No Pride banner to how No Justice No Pride protesters were treated — NJNP senior organizer Emmelia Talarico said that her group experienced violence from Pride attendees, saying there were “bottles chucked at us, trash dumped on us, I got punched, shoved, kicked and spit at.”

It’s important to remember, also, the ways in which Pride — parade, party, protest, all of it — is still a contested and embattled space. In Utah this week, anti-gay protestors in Utah protested the Pride festival; KKK members showed up at Northwest Alabama’s first-ever LGBT pride parade. In many communities, there’s no opportunity for Pride to be just a party, whether people want that or not. In many places, there isn’t a possibility for Pride to be at all. And these are, of course, only examples in the US; elsewhere in the world, these conversations about public celebrations of LGBT identity are fraught in different ways and it would be dismissive to call the practice irrelevant. In Ukraine, “Over 2,000 people marched in Kiev Pride this year, while 5,000 police officers kept anti-gay protesters at bay.” The characterizations of some large, corporate Pride events on the coasts or in large US cities aren’t necessarily applicable to communities elsewhere in the country or the world.

It’s possible that many of those who chanted “SHAME” at DC protesters were once protesters themselves, during the AIDS crisis of the ’80s and ’90s. Maybe the man who said “I fought for 20 years for this, and now you’re going to ruin the parade” was one of them, or maybe he was just referring to his own internal struggle to come out and feel accepted and proud of who he is, or maybe there’s something else happening there personally or communally that it’s not possible to interpret.

Regardless, it’s disappointing that the person worried about his parade being ruined can’t look at the activism around him as a continuation of that fight, another side of that coin. Just because he won his war doesn’t mean it’s over for everybody. A lot of people are still fighting, and have been for a long time. A lot of people need a lot more than a parade. During the AIDS crisis gay and bisexual men and trans women and their chosen families watched with helpless rage while they and their loved ones died in droves, and no one outside the community cared enough to mourn with them or even acknowledge what was happening. Today, many queer and trans people of color are still watching their loved ones die and be killed in droves, and it doesn’t demean or invalidate anyone’s 20 years of fighting to ask the community at large to mourn, to care, to do something.

Besides — queers and many marginalized groups have been legendarily capable of managing to pull off successful protests on the same day we organize successful parties. Both of those things can be part of an effective resistance, and we don’t have to choose one or the other. We don’t lose our opportunities for joy and celebration when we make space for our struggles and the struggles of our most vulnerable, and when we elevate and center those in need. More than that, our celebrations as a community come out of our struggles, and our survival of them, and the ways in which we’ve helped each other survive no matter the cost. The first Pride was a riot, a riot in response to state violence — and specifically state violence that wanted to prevent us from having Stonewall as a space to party and be joyful with each other without fear. Our rage and our joy aren’t at odds with each other; they’re both integral to our history, our present, our future.

Other Pride celebrations that have occurred so far around the US have also been protested — for instance, in Boston, representatives from the Network/La Red, Stonewall Warriors, Workers World Party, National Lawyers Guild and other groups executed a disruption that “called for official 2017 Pride events to stop sidelining radical and revolutionary Black community participation; for Pride to officially speak out against the rash of recent trans murders; for an end to Pride’s lucrative sponsorships from companies that profit off prisons, colonial debt and desecration of Native land; and for a ban on all police and Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents at Pride events.” (Boston also saw similar Pride protests in 2015.)

Last week, Minnesota police officer Jeronimo Yanez was acquitted for the murder of Philando Castile, a Black man who offered no violence or resistance and was still killed in front of his partner and four-year-old daughter — who had to remain calm and nonreactive in the face of a devastating and traumatizing event for their own safety — despite following every rule and directive. Activist groups responded immediately with nationwide protests over the weekend, including some at local Pride events. In Columbus, Ohio, police arrested four protesters from the Black Queer Columbus organization who had planned to peacefully disrupt the Pride parade to bring attention to Jeronimo Yanez’s acquittal and ongoing violence against Black and brown queer and trans people.

Protesters said their goal was to have a seven-minute moment of silence, and said they were protesting the acquittal of Minnesota police officer Jeronimo Yanez, who shot and killed Philando Castile last year. The group was also aiming to “raise awareness about the violence against and erasure of Black and brown queer and trans people, in particular the lack of space for Black and brown people at pride festivals and the 14 trans women of color who have already been murdered this year,” according to Black Queer Columbus.

Four protesters were arrested on charges ranging from disorderly conduct, resisting arrest, failure to comply, and more after “someone tipped officers off about a group of protesters blocking off the parade route,” and, allegedly, when police tried to move the protesting group, “some began to resist.” Three were released on bail; one, Deandre Miles, remained in police custody. A demonstration was planned to call for his release, with about 100 people reportedly attending; Black Queer Columbus issued a statement calling for his release, for the charges against the other three protesters to be dropped, and for “an investigation of the excessive force used by police against peaceful demonstrators.”

Though our method was a silent, non-violent, peaceful demonstration, the CPD immediately opted for unnecessary force in lieu of our civil and human rights. Protestors were assaulted with bicycles, sprayed with mace, jumped on, pushed, pummeled, and chased with horses – all within two minutes of the initiation of the road block. In the process, four Black protestors were targeted and arrested. The #BlackPride4 were taken into custody and held in a CPD van for four hours prior to processing without being provided medical attention.

Deandre Miles was released from custody Monday after supporters posted a portion of his $100,000 bond; all four protesters are scheduled to be arraigned in July.

We’re only about halfway through Pride month; we’ll see more actions, more statements about them, and hopefully no more people arrested or endangered as a result. The central question, however, of what the primary values of the multitudinous and complicated space of Pride could potentially be, will continue long after June — because it’s also tied to questions of what the values of our multitudinous and complicated community are, and who they serve, and who they center. Although we share a history — sort of — not all of us share the same needs. Our future as a community (as loosely defined and organized a community as that is) has never been certain, and in this current administration some parts look very cloudy indeed. So when we look to our past, the pertinent question is maybe: What are we proud of? The moments of complacency, or the moments of struggle? What was risked and what thorny and painful difficulties had to be undergone for the achievements we’re now so grateful for? What tensions were raised and who was challenged? Historically, how have our community’s celebrations been inextricably tied to our resistance, our willingness to disrupt and cause discomfort? When we remember and repeat to ourselves that the first Pride was a riot led by transgender women of color, how are we enacting the next steps of that legacy rather than just acknowledging it?

It’s worthwhile, perhaps, to ask the same questions about our present. What are we proud of? Is it the abstract unity of our acronym of identities, or is it the concrete work we’ve done and are still doing to protect and uplift each other and ourselves? Historically, queer people have always been found at forefront of social justice movements that advocate for a variety of marginalized groups, not just queer-specific ones (because, of course, queer people are everywhere, and every other issue affects us), and that tradition continues to this day. When we think of who is doing that work right now — people like Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, Yahaira Carrillo, Opal Tometi, Prerna Lal, Candi Brings Plenty, and so many more — how can Pride honor and materially support that work? Is Pride giving a real platform and honor to that work, or lip service? Is it really antithetical to celebrating ourselves to be proud of our protests? Maybe most fundamentally, does the larger (white and cis) LGBTQ community want to feel proud… or just comfortable?

“Maybe most fundamentally, does the larger (white and cis) LGBTQ community want to feel proud… or just comfortable?” Yes. This. Absolutely right on.

I got to marshal at London last year, and the atmosphere was amazing, and I was so high on it the whole way… and so angry. Happy angry if you will. I’m angry that the real targets of Orlando were brushed under the carpet (still angry). I’m angry about the people at work who say they need a ‘straight pride’ and that they’re fine with homosexuality ‘but there’s no need to shove it in my face’. I’m angry about the gay jokes I still have to put up with at work, that I had to put up with at school, that kids still put up with at school. I’m angry that I couldn’t possibly answer honestly when the people I’m working with at the moment (am in E Africa) ask me about whether I have a husband, and that’s just me visiting- I’m angry for the people here who won’t ever have a choice.

I’m angry about Brexit and Trump and suicide and HIV and loneliness and toxic bigotry in the name of religion, and I’m angry about members of the LGBTQ+ community throwing people who don’t look straight (or safe) under the bus, and I’m angry about the complacency of the LGBTQ+ community who aren’t suffering, who enjoy the benefits of hard-won reform and freedom without the grace to learn about it or appreciate it, or the passion to clear the path they’ve walked so other people can also enjoy the freedom to live and love.

And I’m a cis white woman, so I also want to acknowledge my privilege, and good grief, if I’m angry, I can’t imagine how others in this community of ours are feeling.

But yeah. Party on. Angry happy party. Because that’s a key element of the protest. None of the haters want you to party and have a good time.

Rachel, this is fantastic. Thank you.

I traveled to attend Pride in DC, but specifically to participate in the equality march and rally that was held the day after the parade, on the same day as the festival. The March was not officially a part of pride, but was also not entirely separate. It was held adjacent to the festival, and I think most people attended both. Many people were not clear on the separation, and assumed the March, and the rally afterwards, with speakers, was part of the festival. But it was specifically organized WITHOUT the corporate sponsorship, and intentionally to include people who may typically feel left out of pride. It was held at the same time, I think, with the intention of drawing more people, and I believe they initially attempted to organize WITH Capital Pride, but all they got was listed as an event on the website, and the ability to hold the rally a few blocks from the festival, on the national mall.

We missed the parade the day before, because I was sick. I woke up to reports about the parade being interrupted by NJNP. I was impressed with them, and felt like their issues with Pride echoed things that have always bothered me about pride, no matter where I’ve been (Buffalo and Rochester NY, Columbia SC and D.C.) Pride has always felt like just another place businesses and politicians can try to make money off the community, and has always felt very focused on cis white gay men. And yet, I’ve always participated, because at least it’s SOMETHING.

I live in NJ and was abroad during my local pride and or Philly pride; I haven’t been able to go to a Pride event yet, and I halfway planned to attend NYC’s, but I’ve been feeling very conflicted lately on whether or not I should. I’m not sure what’s in the cards for me this Sunday or how I feel about it yet. As a student of gay history, I’d love to have been NYC Pride do what LA did, and am a little saddened that they haven’t.

Thank you for writing this as this is the important stuff we need to be reminded of.

Since Stonewall Police and major corporations have gone from the enemies to allies and supporters. Their presence overtly advocates tolerance and diversity to observers.

The corporations learned long before the politicians that discrimination is not good for business. Corporations have been tremendous allies for the LGBT community, as seen in their lobbying against anti-gay legislation in Indiana and North Carolina, threatening to leave states that discriminate. DC police fiercely protected all gay bars after Orlando and they also assign gay cops to gay neighborhoods.

Pride is a wonderful event for celebrating our victories in winning our rights and recognizing LGBT people and our allies; if we use this time to ostracize the very people that helped us get here we are, by extension, ostracizing ourselves.

I feel smarter for having read this. Thank you Rachel!

This is so great, thank you Rachel!

Thank you for this Rachel. I am really struggling to come to terms with what happened here in Columbus on Saturday, and what has happened since. I am just so shocked that CPD can pull this at our event, and our organizing non-profit isn’t even holding them accountable. Your writing is beautiful, and really dives into all the issues that allowed for it.

Rachel, thank you so much for writing this, you’ve managed to pinpoint all of the issues that make me feel weird about pride, with great deft and balance.

I’m so grateful for this article, thank you!

i will never, ever forget the disruption at Pride here in Denver in 2015, led by queer youth of color on behalf of Jessie Hernandez, queer Latinx 17 year old murdered by the Denver police. I participated in that disruption as a white accomplice/ally. White people screaming at the youth, including members of Jessie’s family, about ruining “their” pride and threatening to have all of us arrested. And not only at the disruption but later when we marched with banners and signs with Jessie’s picture/name. Cussed at, yelled at, by white gay men and lesbians. I will never, ever forget it, and I will never, ever go to Denver pride again except to protest it. As long as Pride is sponsored by corporations that detain, incarcerate, and bomb black and brown bodies, destroy the land, violate indigenous sovereignty…I mean, what kind of pride is that?

if white people think their pride is ruined because queer/trans people of color ask for/demand space and not to be killed, that’s just white pride. And I am no way in favor of celebrating that. I am here for collective liberation, not assimilation into violent capitalist white supremacist patriarchy.

thanks again for this article, I so appreciate having this named here.

Thank you for this article, Rachel!

Rachel this is so thoughtful and well expressed. Thank you for taking the time to articulate the many facets of this. So thankful for and proud of the work you do!

this is great coverage, thank you for reporting on it — please continue to follow this.

one of the central concerns No Justice No Pride (disclaimer: i participated in this action, so, biased) shared with the community was the fact that there is a huge police float at Capital Pride. dc’s metropolitan police department poses an active threat to trans and queer people in dc, so it’s astounding and awful that cops are allowed to have a float. i am inspired by the activists in other cities (thinking of new york this past weekend) who also disrupted their own pride parades.