Header by Rory Midhani

Header by Rory Midhani

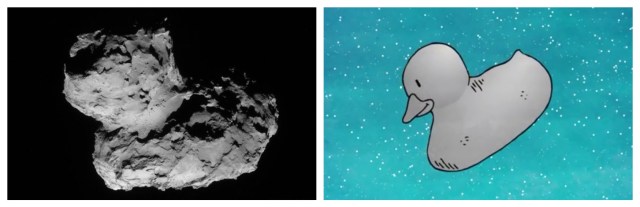

On Thursday, millions watched with bated breath as robotic lander Philae touched down on the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, a rubber-duck-shaped chunk of ice, rock and dust over 500 million kilometers from Earth. Although there were several tense minutes as radio contact cut out, it was soon confirmed that Philae had stuck the landing, making the European Space Agency-led mission the first ever to successfully land an object on a comet. Philae and Rosetta will now stay there to make as many observations as possible. The data will help scientists learn more about where the comet came from, the origins of life on Earth and the evolution of the solar system.

“I think that Rosetta is one of the most bold and interesting projects in the entire history of the study of space objects,” said Svetlana Gerasimenko, a Ukranian astronomer and co-discoverer of Comet 67P. “There have been other missions which provided valuable scientific results about comets and our Solar System, but those were short-term missions providing a transient meeting with comets and allowing only remote investigations. Rosetta will allow long-term exploration of the comet, and this prolonged period of study will provide us with valuable information.”

Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, the “singing” comet. Images via ESA. ESA has a really cute and easy to understand animated video about Philae and Rosetta on YouTube.

Frustratingly, in an event some are referring to as #ShirtStorm, Rosetta Project scientist Matt Taylor was seen throughout last week’s historic landing giving interviews and taking selfies in a shirt plastered with sexualized female pinups. As STEM Women wrote, this effectively tells the world and our next generation of STEM workers that sexism is still very much part of our professional culture. Taylor changed his shirt later in the day and subsequently issued an emotional public apology.

But I’m not here to discuss dudes and their feelings. Instead, I’d like to draw your attention to one of my favorite historical women in science: Caroline Lucretia Herschel.

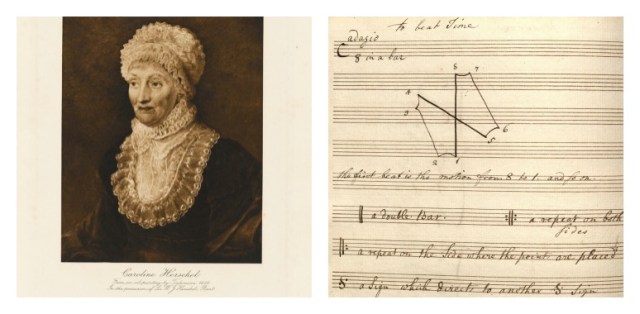

Left: Caroline Herschel, from an oil painting by Tielemann, 1829. Right: A page from Caroline’s music book showing conducting patterns and notes on music notation. Via Yale Library.

Caroline Herschel was born in Hanover in 1750, the fifth of six children. In her youth she suffered from smallpox at age five and typhus at age eleven, leaving her with a severely scarred face and stunted growth. Assessing Caroline’s marriage prospects as dim, her parents treated her as an permanent unpaid scullion and took measures to ensure that she would never leave.

In stark contrast to her older siblings, Caroline was frequently whipped for disobedience, starved for food, and barred from receiving higher education. She wasn’t allowed to learn French, in case she developed ambitions to become a governess. She wasn’t trained in the family business as a milliner, although she was encouraged to learn just enough to deal with the household clothes and linen. When an extra servant girl was hired, she was given Caroline’s room and bed to share. Yet in spite of these obstacles, Caroline was highly motivated and self-sufficient. She learned to read and developed excellent penmanship, a rare point of pride during her early years.

When Caroline was 21, her older brother William took pity on her and wrote home asking permission for her to join him in Bath. When the family refused, William offered an annuity to pay for a maid to replace Caroline. He went to Hanover personally to fetch her, and the two made a quick and strategic departure when the head of the household was out of town. During the trip, they sat atop the carriage and William — a professional musician with a keen, quirky interest in astronomy — showed Caroline the constellations.

Once in England, William began giving Caroline lessons in English, singing, arithmetic, harpsichord, and bookkeeping for the household accounts. She thrived, dealing with the household linens, preparing the menus, doing the shopping, and acting as hostess in the salon. Soon Caroline was even on track to become an independent concert singer. When they later opened a small millinery business on the ground floor of their house to supplement household income, Caroline picked that up too, quickly turning it into a successful business. Enabled by his sister’s rigorous contributions on the domestic labor front, William now dedicated an increasing amount of time to astronomy.

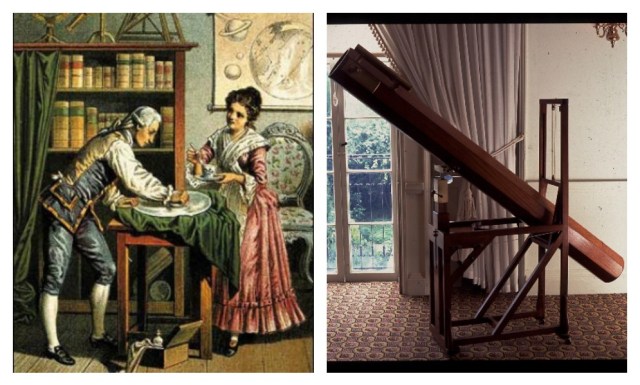

Sometimes Caroline used to spoon feed William while he was working, to make sure he didn’t pass out. Left: A Victorian colored lithograph of the Herschels at work, 1890. Right: Replica of the Herschel’s seven foot telescope via Herschel Museum.

With Caroline’s help, William began to experiment with building telescopes. After a failed attempt that autumn to build a large refractor magnifying telescope (Caroline’s 18 foot paper mâché tube kept bending), the pair decided to construct a five foot long reflector telescope. Soon, the Herschel’s drawing room became a stand construction workshop; a bedroom became a glass grinding operation; and the whole house took on the odor of horse dung, which was pounded into a dried, non-porous loam mould for mirror casting. By 1774, they had successfully assembled the telescope, an instrument of unparalleled power and clarity which used curved mirrors to gather and concentrate light.

With William operating the telescope and Caroline taking notes, the siblings began to compose a new catalogue of double stars and to develop a system of recording the exact time and position of any unusual stellar phenomena. Although Caroline was now being offered solo singing engagements, she turned them down to stay with her brother. William also began to dial back his music career to spend more time observing the stars and building better telescopes.

In early 1781, William and Caroline moved to a three story terraced house with a garden out back for their telescopes. Caroline took over many of the logistics of the move, staying behind for several days to oversee the selling off of the linen stock from the millinery business. Yet it was during this time that William first spotted the celestial object that would put the name “Herschel” on the map.

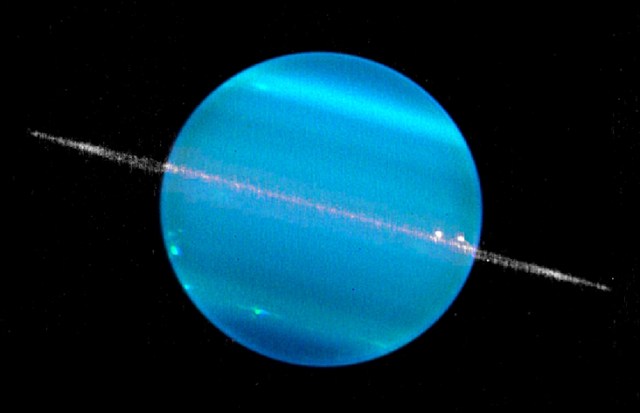

Composite image of Uranus via NASA.

At first, William wasn’t sure what he was looking at — and indeed, he didn’t even bother to look for it again until three nights later. When Caroline returned, they made regular observations from March 21 to April 6, carefully measuring and documenting the discovery to confirm that it was neither a comet nor an already known star, and that the large, steadily moving body was in regular orbit around the sun: the planet now known as Uranus. Although both Herschels maintained journals corroborating their joint work on the discovery, the story of Uranus’s discovery was romantically retold when it went out to the public as the work of a solitary male genius who had a “Eureka” moment on March 13, 1781. Caroline never publicly commented on this.

Following the planet’s discovery, King George III appointed William the King’s Personal Astronomer at Windsor, with a royal salary of £200 per year. Caroline and William moved to a new home closer to the king, and the siblings started a business manufacturing high quality telescopes. Caroline ground the lenses for the telescopes and continued on as housekeeper and business manager, assisting William in relentless all night “sweeps” of the stars. William gave her training in his observation techniques so that she could become a genuine “assistant-astronomer.” In 1782 he also built her a special lightweight sweeper in the traditional refractor design, instructing her “to sweep for comets” while he made observations in the 20 foot telescope above.

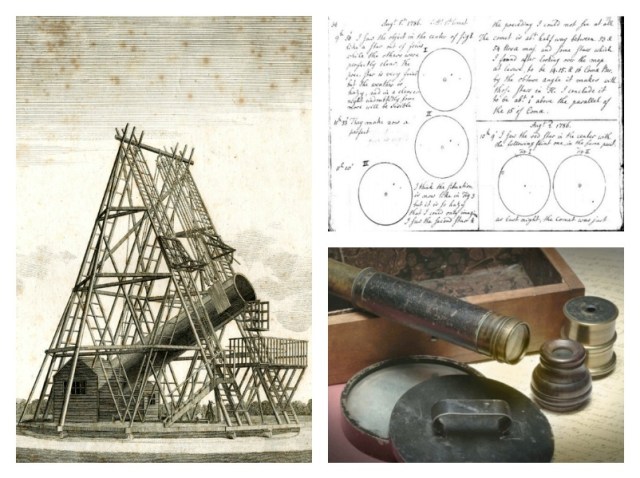

Left: Engraved illustration of the Herschel’s 40 foot telescope, first published in Philosophical Transactions, 1795. Right: Caroline’s notes on her first comet discovery, and her lightweight sweeper telescope. Via Arxiv.

In Caroline’s first year of comet sweeping, she struggled to find her place in the skies and was frequently interrupted by her brother as he shouted out observations he wanted her to take down. Aside from interrupting her concentration, stopping to take notes also reset Caroline’s night vision, which can take as long as 30 minutes to establish its full sensitivity. Her work as an assistant astronomer during this time was invaluable, however, as she able to fetch and carry instruments for William, document each of their trials and results, complete the complicated and exhaustive calculations that accompanied their research, and annotate all discoveries according to their “zone clock” (a special design set to match the position of the stars rather than the sun), protecting her brother’s night vision the whole while.

Though the odds were against her, Caroline carried on learning about the heavens and conducting her sweeps — and eventually, she was rewarded. On August 27, 1783, Caroline had a breakthrough, identifying a small “associate nebula” in Andromeda for the first time with her lightweight sweeper. She was credited in print with the discovery (now known as NGC 2360) when William released his revolutionary paper, “On the Construction of the Heavens.” By the end of the year, Caroline had identified two more nebulae, including M 48/NGC 2548, and NGC 6866.

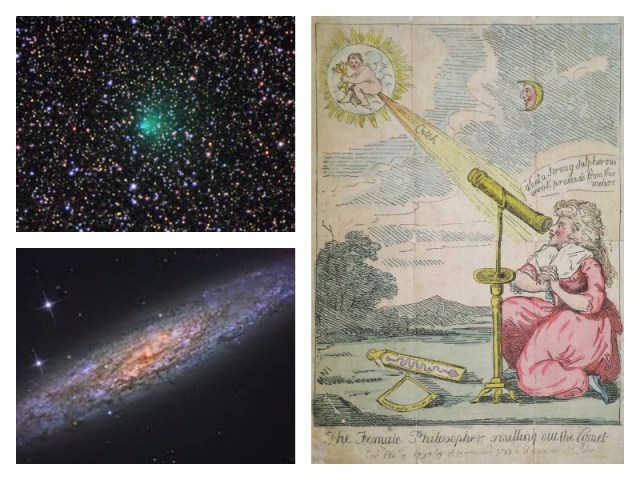

Top Left: Comet 2P Encke, a periodic comet which Caroline observed on November 7, 1795. Image via Cometography. Bottom Left: NGC 253, which Caroline discovered. Image via NASA. Right: A comic poking fun at Caroline “smelling out” a comet. At the time of its publishing, she was by far the most famous female astronomer in the world.

As word of the Herschel’s discoveries spread, their house became a hub for prominent scientists of the day to gather and discuss their works. With the assistance of scientifically-minded explorer Joseph Banks, William received a grant from King George III to construct a new 40 foot telescope, the largest ever built at the time. In April they moved houses again, and Caroline began overseeing workmen in construction of the monster telescope, both with and without her brother.

By July of 1786, Caroline had set a strict routine for herself as an astronomer rather than a housekeeper. She checked the calculations of William’s nebulae by day and made her own sweeps up on the roof by night. Using her specially constructed “hunter’s telescope,” on August 1, 1786, Caroline spotted an object moving through the sky. Caroline’s triumphant finding (Comet C/1786 P1 [Herschel]) became known as the First Lady’s Comet. Its publication by the Royal Society — an almost unheard-of rarity for a female correspondent — catapulted her to international fame. At the time, only about thirty comets had been identified and recorded.

Caroline Herschel at age 92.

Caroline made her second comet discovery in December, and in 1787, King George III gave her a yearly stipend of £50 for her work. Prior to this, no British monarch had ever granted a woman a salary or even a pension for scientific work. When her brother married neighbor Mary Pitt the following year, Caroline moved out of their shared house. Although she continued to serve as assistant astronomer to her brother, she increasingly carried out independent research. Some significant discoveries included:

- Comet C/1797 P1 (Bouvard-Herschel), the 13th closest approach of a comet to Earth,

- NGC 253 aka. the “Sculptor Galaxy,” a large, almost edge-on spiral galaxy,

- the second satellite of the Andromeda galaxy M31,

- M110 (NGC 205), which is a rather small spheroidal instead of a regular elliptical, and

- 35P/Herschel–Rigollet, a periodic comet with an orbital period of 155 years

…among others. She also made contributions to existing knowledge of previously discovered comets and nebulae.

Following William’s death in 1822, Caroline moved back to Hanover and cataloged all the discoveries she and her brother had made. Upon the release of the extensive tome, Caroline was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1828. She was admitted as the first female honorary member of the Society in 1835, and in 1846, she was recognized for a lifetime of devotion and achievement in the field of astronomy with the King of Prussia’s Gold Medal of Science. She died two years later, at the age of 98.

Caroline Herschel continued to hold the record for the most comets discovered by a women until the 1980s, when Carolyn Shoemaker broke her record. She is remembered today in the names of half a dozen comets, an asteroid discovered in Vienna, a crater on the moon bearing her name, and a poem by Adrienne Rich.

Notes From A Queer Engineer is a recurring column with an expected periodicity of one month. The subject matter may not be explicitly queer, but the industrial engineer writing it sure is. This is a peek at the notes she’s been doodling in the margins.

Thank you for telling this amazing and important story instead of talking about dudes and their feelings. We get too much of that as it is!

I wouldn’t ordinarily read about anything science-related and I’m really glad I decided to read this anyway! I learned a lot from this interesting and eloquent article. Thanks!

I’m pretty sure I heard Rich read that poem back in ’83 or ’84. I’m also pretty sure that the two readings of Rich’s that I heard were key events in making me the lady I am today. Also, I’m ashamed that I hadn’t learned more about C. Herschel before now.

Oh that’s awesome! I only heard about that poem this week, but it’s lovely, isn’t it?

Thank you, this is fascinating!

Caroline Herschel is one of my favorites!

Yes! We need more expanded versions of history. Thank you so much for this.

If you’re ever in Bath, the house in which they first set up in is now a museum! I went this summer and the house is so full of history. It costs to get in but it’s totally worth it to learn about this fantastic woman. Also there’s more humorous old-timey illustrations of comets and space things. They liked to show them as people shining light out of their asses a LOT.