Header by Rory Midhani

Header by Rory Midhani

We’re 369 days into this presidency, 285 days to midterms, and I’m feeling ready to pour myself into change making. We’re reclaiming what’s ours, goddamnit. 2018 is our year, and I’m going to draw strength from every nook and cranny. All that’s before me, all that’s beneath me, everything around me.

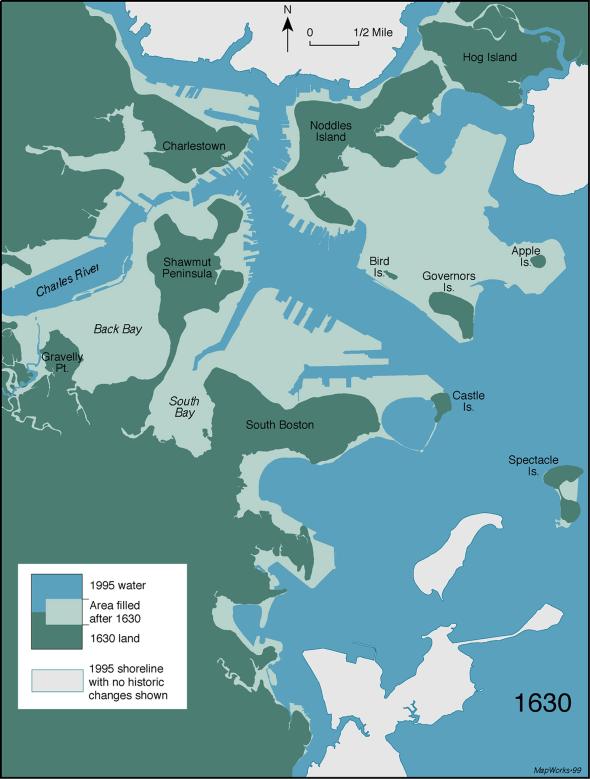

In Boston in particular, what’s around me is land that, until a few hundred years ago, mostly used to be sea. About one-sixth of Boston today lies on made land, including most of the area set aside for Logan International Airport (visible below as the light green fill connecting Bird, Apple, and Governors Islands).

Recently, I’ve been making my way through Nancy Seashole‘s Walking Tours of Boston’s Made Land, feeling inspired by the huge changes that have taken place here. Here are a few of them.

The original shoreline, from 1630, is visible in dark green on this map. Land made between 1630 and 1995 is light green. Image from the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library via National Geographic.

Boston’s first landmaking occurred in the 1630s, when Puritan settlers began to fill in and straighten out their shores using a technique known as “wharfing out.” As the name suggests, they built wharves (platforms extending from the shore over the surface of the water), then filled in the spaces between the platforms. As these activities made it easier for boats to land in the area, the place became known as the Town Dock, and later, Dock Square. The area continued to be filled in, including in 1728-1729 when the town collected trash from nearby taverns and craft shops to fill the entire southern half of the dock with shoe leather, broken dishes, clay smoking pipes, and other discarded materials. In 1734, a public market was built over top. Though the market was quickly torn down by a mob, in 1742, Faneuil Hall was erected as a gift to the town from wealthy French merchant Peter Faneuil.

This past August, founder of the New Democracy Coalition Kevin Peterson called on Mayor Marty Walsh to rename Faneuil Hall due to Faneuil’s involvement in the slave trade. (Worth noting here: Boston was a center for the slave trade throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, and like much of New England, its early economy was built on slavery. The earliest slaveholder in the area is believed to have been Samuel Maverick, who arrived in 1624 with two slaves. The first slave ship to Boston arrived from Barbados in 1638, and three years later, Massachusetts became the first American colony to formally codify slavery. This remained in effect until 1783.) Peterson suggested that Faneuil Hall be renamed after Crispus Attucks, a black man who was the first person killed in the Boston Massacre. The idea didn’t get traction with Walsh last year, but again: no time like the present.

Faneuil Hall is currently closed for renovations.

Present day wharf on the Charles River, Cambridge.

Present day Charles Riverbank.

During the 1800s, most land creation in Boston was accomplished via sea walls, aka “dikes.” The outer perimeter of the fill area would be marked by a stone sea wall, then gravel, dirt, and other materials would be dumped inside. Fill would continue being deposited until the level of fill rose above the level of high tide… or at least, that’s how it was supposed to work.

When Boston’s Suffolk Street District was built in 1829, the city constructed a mud dike and filled the intervening flats with mud. Because the water in Back Bay was kept abnormally low by a dam built in 1821, the area was not originally filled above the level of high tide. Water levels changed when Back Bay was filled in the late 1850s, and Suffolk Street District began flooding regularly with storm water and sewage. (At the time, it was regular practice for sewers to discharge raw sewage at the nearest shoreline, where it was supposed to be carried off at the ebb tide.)

Nearby Church Street District (now Bay Village), experienced many of the same problems, having also been built in the 1820s/30s below high tide. Explains Seasholes in Walking Tours of Boston’s Made Land:

In the 1860s the city considered several solutions: fill up the cellars and abandon then, install pumps to drain the sewers, or raise the ground level of the district by adding more fill. Surprising as it may seem today, the city chose the last alternative and in 1868 began raising the level of the Church Street District. Buildings were jacked up and underpinned, gravel fill brought in by railroad was placed under them, and then the buildings were returned to their owners.

The same procedure was followed in Suffolk Street District from 1870-1872, and Northampton Street District in 1874. Today, if you walk around those areas, you can still see the impact of this activity on the landscape and in the architecture. These houses on Melrose Street, for example, appear not to have been raised, as their bottom floor windows look out below street level.

Windows below street level on Melrose Street.

By the way, we’re not dumping raw sewage straight to the water anymore. Here the Metropolitan District Commission has large sewers parallel to the banks of the Charles, intercepting the old sewers that once flowed directly into the river.

Today, parts of the South End that were filled in the 1830s remain much lower than those filled in the 1850s and 1860s. The Tremont Street area (which was never raised above high tide) is protected by a pumping station on Union Park Street that has been in place since 1915. Though this measure has been largely effective at protecting residents over the years, low lying areas must now also be prepared to deal with the effects of climate change. Currently, sea levels are predicted to increase nine inches by 2030, 21 inches by 2050 and 36 inches by 2070.

Per Boston’s “Climate Ready” report:

Due to sea level rise, significant flooding will result from storm surges less powerful than those causing flooding today. The South End and East Boston can expect to see the greatest increase in land exposed to stormwater flooding as sea levels rise and rainfall becomes more extreme. … In the near term, areas near the Courthouse and adjacent to Fort Point Channel will be exposed most frequently to coastal flooding. By 2050, portions of the Orange Line will be impacted by major flood events. Mid century, exposure will extend to the Conley Terminal, Raymond Flynn Marine Park, Fan Pier, and Joe Moakley Part. Later this century, much of the Seaport will be exposed to flooding during the average monthly high tide.

The city’s most recent urban development plan, released November 2017, outlines infrastructure to block floodways into East Boston and Charlestown via elevated pathways and parks. It also calls for raising Charlestown’s Main Street by two feet.

View of Charlestown and Tobin Bridge from South Boston.

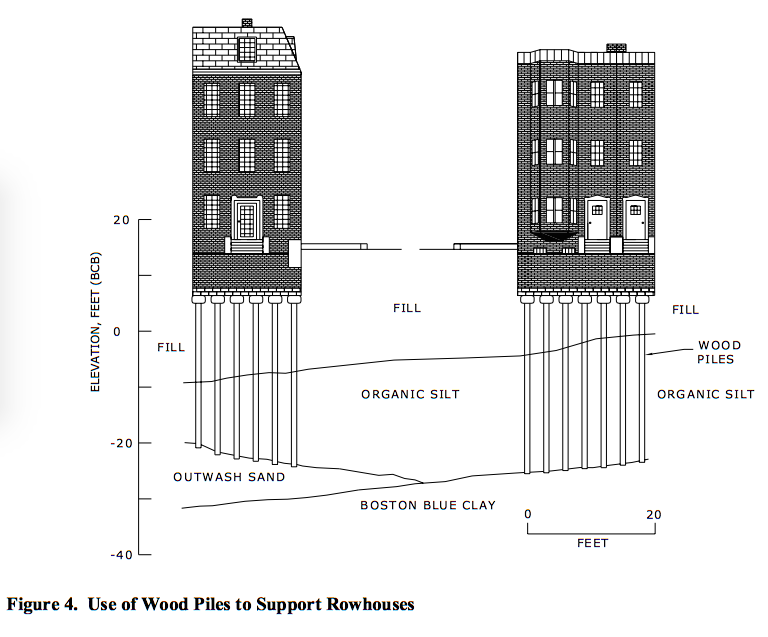

A present day pier off Boston Main Channel.

One thing I find particularly interesting and impressive about all this made land is that structurally, it’s still held up by the original wooden piles. When the last continental glacial ice sheet retreated, it left behind a variety of interesting soil formations. The carved out area of Back Bay was an ideal location for developing thick marine sediments, which hardened when they were exposed to air; elsewhere, glacial meltwaters caused localized sand and gravel deposits to form. So when humans wanted to make land, they usually wound up placing loose fill over top of soft mud deposits. To make a solid foundation, trees were stripped of their limbs, turned upside down, and driven into the ground with a falling weight (“pile driving”). Once installed, these wood piles became important structural elements for the area.

Though I doubt the original engineers intended or expected these wooden piles to last hundreds of years, they’re doing just that — and holding up just fine, so long as the wood stays submerged below water lines. Writes James Lambrechts in “The Problem of Groundwater and Wood Piles in Boston: An Unending Need For Vigilant Surveillance” (!!),

The major problem with wood piles occurs when groundwater levels drop and expose the wood at the top of the pile to air, which will trigger spores of fungi that are naturally in the wood to produce the wood rotting organisms. Once started, the fungi will slowly and steadily work through the wood cell structure and cause the wood to progressively weaken, eventually to the point where there is not enough sound wood left to support building loads. The rotting seen most often works its way from the perimeter in towards the center of the wood pile. In some instances it may take only a few years for most of the pile top to rot away, but in other cases it may take a few decades, and the rate will often vary from pile to pile (or from tree to tree).

Wooden piles are usually replaced with steel or concrete today.

Notes From A Queer Engineer is a recurring column with an expected periodicity of 14 days. The subject matter may not be explicitly queer, but the industrial engineer writing it sure is. This is a peek at the notes she’s been doodling in the margins.

Those wood piles are… well, they’re something. I knew almost none of this despite the fact that my therapist’s office is on Melrose lol. This was so interesting – thank you!

Glad you liked it!

Okay now you made me want to visit Boston… never been…

Would recommend!

Venice was also built on wooden piles, many of which are over 500 years old and possibly much older. So it seems likely that those 19th century engineers did foresee them lasting a pretty long time.

Good point. :)

This was a really interesting read! Thanks for writing it!

<3

Ooooooo thanks for this. I have so so so many thoughts about the infrastructure of this (my) city and what’s going to happen to it as the ocean keeps flooding in. And I love learning more about the palimpsest-style evidence of the history of this city’s construction – taking the train in to North Station a few weeks ago I was admiring all the stray concrete and wooden structures left in the river underneath the current tracks and bridges.

And Seashole’s book is on my wishlist now. Do you have any other book recommendations related to literally anything having to do with Boston’s infrastructure/history, especially by female authors (I hate how 95% of the books Amazon suggests to me about historical/scientific/pretty much all nonfiction are by male authors)?

I don’t personally, but Seashole’s guide has a list of references and recommended reading in the back! There are also a lot of walking tours around here in the summer, I feel like. :)

This is so cool!! I love finding out the history of housing in different towns and this is so new to me.

Really interesting to read this considering the recent flooding on Boston due to the “bomb cyclone” blizzard earlier this month. (I live on the North Shore and we had it up here too! From what I understand this will only become more common…

soooo interesting! thanks laura!

Love learning about my weirdo, complicated-history-having city. Thanks for writing, Laura!

Wow. I’m definitely reading the Lambrechts piece. I can only imagine the insurance claims and legal battles if the piles of wood under the city (I had no idea) aren’t maintained/replaced and major erosion occurs. At what point does erosion and flooding become an endemic feature / “act of God” type event for which insurers won’t pay?