My elementary school playground was as ordinary as it gets. It had a jungle gym, seesaws, a slide, and rowdy kids all over. I was usually found gabbing with my girl gang about the latest issue of Seventeen Magazine in some far corner of the playground. All was well with the world, or so I thought.

I had no clue that I was playing on top of one of the country’s most toxic waste sites. I didn’t know that my hometown, Brunswick, Georgia, is just one of many Black communities in the US facing environmental degradation. For example, less than an hour away from where my father and grandmother live in rural Eastern North Carolina, Black neighborhoods are being sprayed with pig feces and urine produced from nearby industrial hog farms. After three years of crisis, the predominantly Black residents of Flint, Michigan still don’t have lead-free water. Environmental problems are hitting Black neighborhoods particularly hard, but going unresolved because Black lives are deemed less valuable than others. A lot of us are being left in the dark about harm being done to our environment.

Growing up, I never heard bad things about Brunswick’s smelly plants and their emissions that painted our air brown. Since these industries created living wage jobs for working-class men, folks shed a positive light on them. However, as an adult, I learned that my hometown has paid an enormous price for supporting polluting companies, such as Hercules Inc., a chemical and munitions manufacturer that operated a plant in Brunswick from 1920 until being bought out in 2010.

At the Hercules plant, workers extracted substances from pine stumps to be used in various commercial products. One of those substances was toxaphene, a pesticide that became popular with Southern cotton and soybean farmers in the 1960s and 1970s. Over the years, studies found that toxaphene exposure causes thyroid and liver tumors in animals and seizures and respiratory problems in humans. The Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry warns, “Breathing, eating, or drinking high levels of toxaphene could damage the nervous system, the liver, and kidneys, and even cause death.” Today, toxaphene is internationally banned, but by the time Hercules stopped producing it in 1980, toxaphene waste had already seeped into the soil beneath the plant and had also been dumped into a local creek and a landfill.

The landfill, called Hercules 009 Landfill site, was named one of the most hazardous waste sites in the US by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1984. At the southeastern border of the site sits Altama Elementary School, where I attended school from 1992 to 1998.

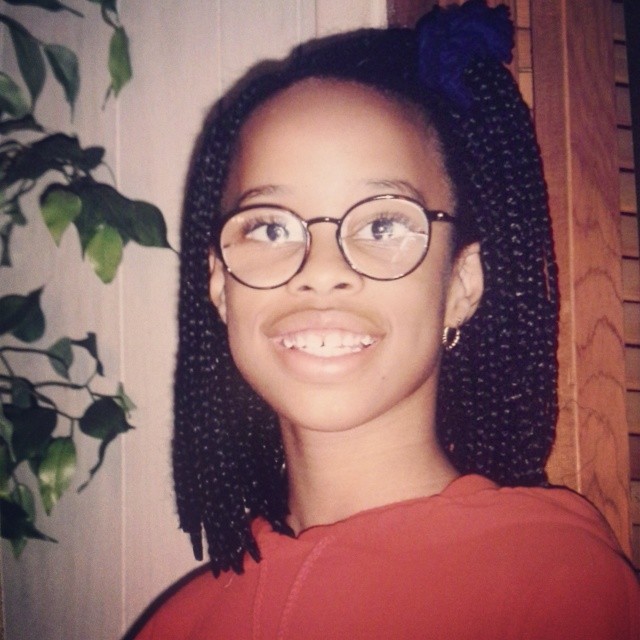

Neesha during their time at Altama Elementary school circa about 1996

My two older sisters and younger brother are also Altama alumni, and my maternal grandmother worked in the school’s cafeteria for more than a decade. We never heard about toxaphene waste traveling through a drainage ditch from the landfill onto our school grounds. Turns out that my formative years were spent playing in contaminated soil.

Hercules 009 is just one of four Superfund sites in Brunswick. The federal Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 established the Superfund program, which calls for the cleanup of the most toxic waste sites in the country. Superfund sites are potentially harmful to humans, animals, and the environment.

A 2007 map of Hercules 009 Landfill Superfund Site via Glynn Environmental Coalition

During the mid-1990s, toxaphene waste was removed from the back of Altama, and the EPA website currently states, “Site contamination does not currently threaten people living and working near the site.”

Although conditions are reportedly safe, project manager Daniel Parshley from the Glynn Environmental Coalition (GEC), a local environmental nonprofit, says the soil at the school has never been appropriately tested for contaminants. GEC is involved in community organizing, advocacy, and providing technical assistance to Superfund sites to assure “a clean environment and healthy economy for citizens of Coastal Georgia.”

In 2005, the EPA Office of Inspector General found that the method being used by the EPA, Hercules, and the GA Environmental Protection Division (EPD) to analyze the amount of toxaphene in the soil at Altama was erroneous and inadequate. This flawed method has also been used at Hercules’ other Superfund site in Brunswick.

Ever since learning about my alma mater’s toxic history, I worry whether me and my siblings were affected by these chemicals. I speculate whether toxaphene exposure contributed to my grandmother’s death from cancer in 2006. Should my family follow the lead of others who are suing because of exposure to pollution from Hercules?

Whether we have a case or not, the former Hercules plant is still a cause for concern in my hometown. Pinova Inc., the company that bought out the plant in 2010, was issued an enforcement order by the state EPD for noncompliance with their air permit in October 2016 and then another one this past December for a long list of Air Quality Act violations. The trend of corporations putting themselves before the health and wellness of Black folks in Brunswick is alive and well.

Rev. Jeffery Muchison is a Black pastor in Brunswick who wants to see big business and city government do right by his neighborhood. A member of the Magnolia Park/College Park Neighborhood Planning Assembly (MPCPNPA), Muchison is a witness to how corporate decisions, as well as government inaction, negatively impact the health and well-being of his neighbors.

The assembly’s currently fighting against a waste and recycling facility called Liberty Roll-Offs & Recycling just north of Magnolia Park, a historically Black neighborhood. When Liberty Roll-Offs opened in 2008, only construction materials were recycled there. Over time, the facility expanded to receiving solid waste materials, bringing a distinct stench into the neighborhood along with other nuisances. Although the facility has brought 50 to 60 new jobs into the neighborhood, it’s been at the expense of residents.

“Those residents have been complaining about rodents, the odor, the big trucks that come out from the company,” Muchison says. “Sometimes liquids are draining out of the trucks onto the streets, and it’s got a terrible odor to it.”

Neighborhood residents with asthma have gotten sicker since the expansion of Liberty Roll-Offs. The facility’s rotten cabbage smell, rats, noisy trucks, and fires from their wood chip stockpiles are deteriorating the quality of life of the entire neighborhood. Magnolia Park is unfortunately in a worse predicament than when I was baby-sat there more than 20 years ago.

Liberty Roll-Offs claims that none of their waste drains into the ditch surrounding Magnolia Park, but MPCPNPA members aren’t convinced. Members also aren’t sure if the company has a municipal waste permit, which it should have since they receive municipal waste.

The assembly’s working in partnership with GEC to help spread the word about their demand for the city: To relocate Liberty Roll-Offs far, far away from residential neighborhoods. To forward this goal, members are exploring their legal options, disseminating a petition, and calling for testing of the ditch.

In College Park, a Black neighborhood only a few miles from Magnolia Park, the assembly’s tackling another environmental crisis. Although hurricanes typically weaken into tropical storms before landing in Brunswick, these storms are still heavy enough to cause major damage, including in College Park. When Tropical Storm Irma hit the subdivision this past September, about 32 homes flooded with up to a foot-and-a-half of water.

Since Tropical Storm Tammy in 2005, some houses have flooded four or five times. Muchison’s seen tropical storms in Brunswick get stronger over the years thanks to climate change, so the neighborhood needs a fix now more than ever.

College Park after Tropical Storm Irma. Photo via The Brunswick News

Through their research, the MPCPNPA found that most of the drainage in the area, including from businesses, empties into College Park’s drain. Because the drain isn’t big enough, more water than it can handle comes in during storms, resulting in excessive flooding. In Parshley’s opinion, the culprit of this problem is “the failure of zoning and planning to do adequate stormwater planning.”

MPCPNPA members and supporters have packed City Hall to address the flooding in the past. In June 2017, the city commission contracted with an engineering firm to help with College Park’s drainage issue, and the assembly plans to hold the city accountable until the problem is fixed.

According to an email from City Engineer Garrow Alberson to Muchison, data collection, field investigation, and hydraulic modeling to analyze the drainage system have been completed. There will be a final report on the issue soon. No matter the outcome of the study, it’s still a win for the MPCPNPA because it wouldn’t have happened without their grassroots activism.

The Black residents of Brunswick deserve a clean and safe environment. But as natural disasters increase due to climate change deniers-in-power, their neighborhoods will continue being hit the hardest. Their town, once home to the now-extinct Timucua peoples, will continue to be treated like an endless commodity by corporations under Donald Trump’s presidential administration.

Thankfully community activists aren’t letting the naysayers and polluters win without a fight. As a descendant of people who lived off this land for generations after being stolen from theirs, I know that I, too, have a role in healing the environmental havoc that capitalism and racism has wrought in my birthplace.

This reporting is so thorough and necessary – I’m thrilled to see work on environmental racism here and am crossing my fingers there will be more like this

This was so well-written and so infuriating and depressing. More power to the community activists.

I’ve been loving that AS has been publishing more environmental racism and community organizing pieces recently. They are so rooted in personal expereinces while also being well researched and heartbreaking.

Thanks so much Neesha for this beautiful piece <3

Thank you for this reporting. It’s great reading personal stories like these. Do they know if any of the chemicals in the soil also affecting the air? Could the people there get a super lawyer to sue the city or the offending companies to stop this & maybe getting a settlement?

Thank you for reporting on this, Neesha, definitely need more information on stuff like this

Stories similar to this one have been echoing throughout North Carolina over the past few years–the farms, as you note, but also coal ash and poisonous water near Camp Lejeune–and it’s been disheartening to witness our government’s unwillingness and/or ineptitude when it comes to dealing with the issue. Thanks for shining a light on this issue, Neesha.

thanks for this article, heartbreaking to realize innocent playing was on toxic sites. Gotta keep yelling as much as possible to hopefully get things done. Flint is instructive, for better or for worse. Rania Kalek has a podcast, unauthorized disclosure, and one ep she talked to a guy from project censored, that puts out the most one way or another censored stories in the media. number 1 for 2017 was that

“In December 2016, M.B. Pell and Joshua Schneyer of Reuters reported that nearly three thousand neighborhoods across the US had levels of lead poisoning more than double the rates found in Flint, Michigan at the peak of its contamination crisis”

Hello, First of all I am vegan. I appreciate your thoughts. I think that your hopes will not happen in our lifetime. However, I do believe, the more we publish our expressions of concern , the more they will affect others. People need to be exposed to thoughts many, many times before they start to believe in them. I very much appreciate your the article.

building rapport