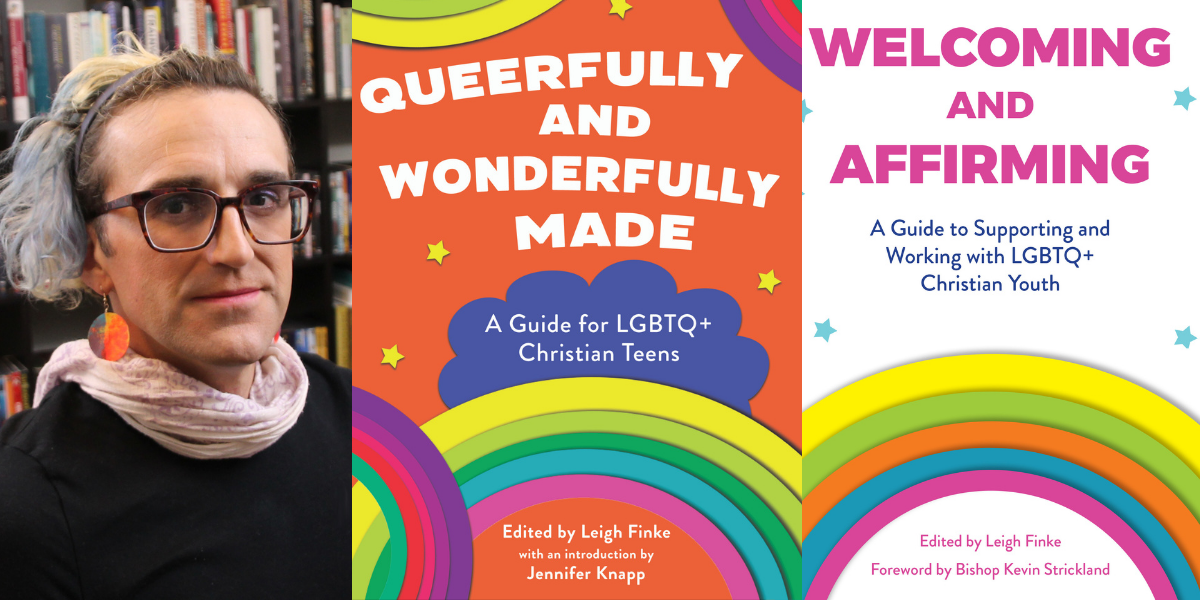

The presence of a single accepting adult in the life of an LGBTQ+ young person can have a dramatic effect on their well-being, according to The Trevor Project. But not all young people can count on the presence of a supportive grown up, and the risks for youth who identify as religious are even higher. Media producer and writer Leigh Finke created Queerfully and Wonderfully Made: A Guide for LGBTQ+ Christian Teens to stand in the gap and provide hope to queer and trans youth in Christian spaces.

As editor, Finke drew together a wide range of contributors, including artists, youth pastors, and advocates (among them our own Kristin Russo), to answer some of the most pressing questions youth encounter, like “Should I Come Out at Church?”, “What if I Want to Change?”, and “How Do Queer People Even Have Sex?” It provides step-by-step advice for responding to bullying, includes examples of role models like Joan of Arc, and is sensitive to the ways diverse contexts can impact a person’s choices about coming out, sexual activity, and more. There is also a companion guide, Welcoming and Affirming: A Guide to Supporting and Working with LGBTQ+ Christian Youth.

In both books, the language is conversational and accessible. Each starts with a user-oriented table of contents/list of questions and ends with a resource guide. Finke defines terms to facilitate understanding without getting bogged down in jargon. From church to bathrooms to Instagram, Queerfully and Wonderfully Made meets teens wherever they are with compassion, clarity, and humor. For example, in a chapter titled “How Should I Be Queer… Online?” the book navigates the murky waters of boundaries, risks, how to react when you make a mistake, and how to avoid comparing your real life to other people’s social media presence (a good reminder for adults too!). The chapter ends with sage advice: “Don’t let the internet interfere with your totally bitchin’ queer Christian life.”

For Finke, the project became a way of answering questions she herself still had as a bisexual trans woman in her 30s. She remembers what it was like to be closeted and not see anyone around her who might be able to help. When she was in high school, she thought about whether to come out as gay — and became an evangelical Christian instead.

“I wish I had these books when I was 15. I needed permission. I needed somebody to tell me, ‘You’re ok.’ If I had had one place to go, one book in my hand, known one person, I could have avoided a lot of trouble.”

Though Finke no longer identifies as a Christian (“for me it will always be the place that I went to get away from myself”), she is “obsessed with how to keep people safe and improve outcomes for queer Christians,” especially youth.

One of the most powerful things about both books is that they operate from the belief that queer people are worthy and that this assertion doesn’t require defending against more conservative views. It makes the brave assumption the person reading the books is queer, or might be, or loves someone who is or might be. There are no rose-colored glasses here — Queerfully and Wonderfully Made talks about how to recognize signs of religious abuse and how to leave a church that is harmful; Welcoming and Affirming offers language to use when a caring adult recognizes that their church isn’t safe for a youth who wants to come out. Finke and her collaborators don’t assume that all Christians are affirming, but they do assert that church should be a safe and inclusive place for all, and if it’s not, that’s on the church — not on queer people.

In an age where so much queer Christian writing is defensive of the right of queer people to exist, this stance is powerful. It gives me hope that perhaps today’s teens can skip the “internalizing all the homophobic garbage” part straight to the “I am made in the image of God” part.

“One of the things I’m hoping these books can do is move the larger conversation around queerness and faith spaces,” says Finke. “We have to move the line so that we just have the right to be ourselves in the first place. Then we can figure out the bigger problems that are leading to these negative outcomes. I’m not interested in the clobber verses or Side A vs Side B. I’m happy for anyone who wants to have those conversations, but I don’t think teens do.”

The visibility and positive media representation of LGBTQIA+ folks has transformed so many of our lives, but it doesn’t always correlate to positive outcomes for queer and trans youth. Even when queer, trans, and questioning young people can see queer and trans adults in the world — even in their own churches — they still need assurance that they, personally, are good and worthy and that they, personally, will be ok. Finke is herself ambivalent about whether youth stay in churches or don’t. She wants them to do what is right for them and will allow them to thrive.

“What I want is for LGBTQ teens to be authentic and whole and realize they don’t have to limit themselves,” she said.

These books are for anyone who wants that too.

I’m glad these books exist, thank you for writing about them!

Historians have debunked this book’s claims about Joan of Arc. Her “male clothing” was just the soldiers’ clothing she had been given to wear for practical reasons, and several eyewitnesses said she continued to wear it in prison for protection because she was using the outfit’s cords to securely lace the long hip-boots, trousers, and tunic together so her English guards couldn’t pull her clothing off when they periodically tried to molest her. The bailiff, Jean Massieu, said they manipulated her into a “relapse” by taking away her dress and leaving her only the soldiers’ outfit to wear, then blamed her when she was forced to put it back on. Medieval theology held that an exemption for cross-dressing should be granted if it was done out of necessity (see the Summa Theologica for example), which the tribunal deliberately ignored since it was composed of pro-English partisans selected by the English government, as is stated bluntly in English government records. The judge, Pierre Cauchon, had served as an advisor to the English occupation government for over a decade before the trial, and all the rest were also pro-English. Many of them later admitted the charges were deliberately false and the trial was conducted solely so that the English could take revenge against her. After the English were driven out of northern France near the end of the war, Joan’s family petitioned the Church to investigate the case, which resulted in a posthumous appellate trial from November 1455 to July 1456 and a reversal of the verdict on 7 July 1456.

Bet you’re fun at parties

Thanks, Acta Diurna! I appreciate learning the real story – it’s always more complicated and interesting than the surface myths we “know.”

These books sound wonderful. A great resource which I’ll be bookmarking for future possible use with youths I work with!

Love this! Thanks for highlighting this resource. I’m a queer person who is also kids and youth pastor, and I am excited to use these materials.