Many queer folks have trouble finding a community when we’re very young and newly exploring our sexualities and gender expressions. In my own experience, I didn’t really know how to connect with my queer peers, the city I live in didn’t host Pride marches until one or two years ago. For Millenials and Gen Z, a large part of our process is mediated by internet access, online communities (for me this meant Tumblr and Her) where we are able to access information on our collective queer histories. Racism, misogyny, and other such systems of oppression dictate what material is readily available to a general audience — so the most visible queer narratives I found were usually those of white people and gay cis men.

As a sapphic teen growing up in the mid-2000s, the lesbian media that I was most familiar with were films like Todd Haynes’ Carol or Abdellatif Kechiche’s Blue is the Warmest Color. I’m a Black Mexican of Japanese descent, so those stories felt somewhat lacking. Yes, they represented what it was like to be a wlw, but they mostly centered the experiences of rich white women. The lives and experiences of those women were nothing like my own, even if we did share our sexual orientation —the way we moved through the world was drastically different. Those movies always left me unsatisfied, how was I supposed to relate to these tragic stories of white women desperately trying to hide their lesbian love affairs?

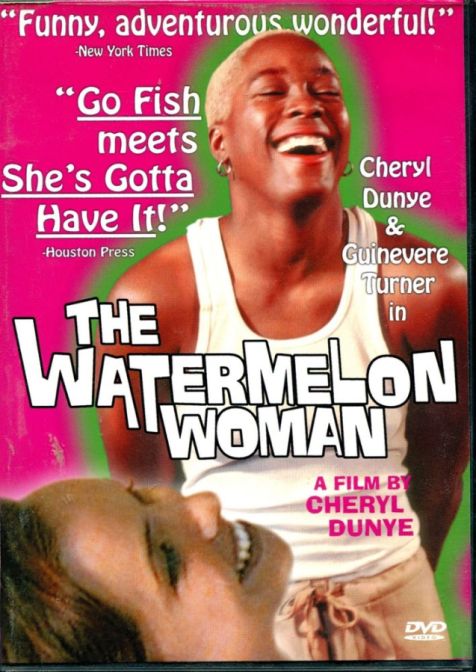

I decided this couldn’t be all sapphic media could offer me, so I began following social media accounts that centered on the experiences of racialized wlw. A couple of months ago I came across a gif on Twitter of a gorgeous Black woman in a pink sleeveless shirt and Bermuda jeans walking into a video store with a compelling caption: “The Watermelon Woman, one of the first movies directed by a Black lesbian”. I quickly googled the title, and felt captivated by a poster for the film — it showed two women (who I would later learn were Cheryl and Diana) with wide smiles over a bubblegum pink background.

The 1996 mockumentary feature film follows Cheryl, a somewhat fictionalized version of writer and director Cheryl Dunye (played by herself) as a young filmmaker trying to piece together the story of an obscure Black lesbian actress credited in the films she starred in as “The Watermelon Woman”. Watching this film felt like a breath of fresh air, not only was it a thoughtful story about how we record queer history and community, but it was also just a fun experience. So much of LGBTQ+ cinema is focused on the pain we experience as oppressed people in a cisheteronormative world, it was starting to feel like the only stories of ours that folks deemed worthy of telling were those of survival and violence. While Dunye’s work does acknowledge the ever-present threat of systemic violence — she ultimately centered queer joy. This film showed me what my upcoming life as a twenty-something queer Black woman might look like.

On the 25th anniversary of the film, Dunye’s creation is as current as ever. Fictional Cheryls’ search (and ultimate invention) of a Black sapphic genealogy reflects a process many young queer women of color go through. The Watermelon Woman reappropriates the narrative of when white people decided this actress didn’t even deserve a name in the credits. Fictional Cheryl becomes determined to find out who she really was, and how she was so much more than the crude term bestowed upon her. Watching the film made me think, How can I as a sapphic Black woman find a tether to my lesbian ancestors and honor them by telling their stories? What if there are as few sources about them as in this film? How can I know their stories? Toni Morrison speaks of this process in her essay “The Site of Memory”, detailing how her creative work is literary archaeology. “On the basis of some information and a little bit of guesswork, you journey to a site to see what remains were left behind and to reconstruct the world that these remains imply”. For Morrison, guesswork and the act of creation are a part of tracing back our histories.

In my own context of Black queerness in Mexico, I could only find traces of it. A couple of documents dating back to the Spanish Inquisition that spoke of a “Mulato” man that dressed like a woman and demanded to be addressed as such, a few queer elders in my community, or brief stories about the homophobic and lesbophobic violence in my fathers’ hometown. When I read Morrison’s words I understood that her suggestions for the preservation of Black history worked especially well for Black queer histories. When we are faced with multiple systems of oppression that seek to eliminate our presence and our history, as queer youth, part of our journey to find and honor our queer lineage is to take the pieces left to us and fill in the gaps with joy. In a world that insists on teaching us that only tragedy and pain come forth from rebelling against heterosexuality and strict gender roles, my own constant form of rebellion is to reclaim the stories of my ancestors and narrate their lives from a place of dignity. Our lives are so much more than pain and oppression, we have also blossomed and found happiness living in our truth, with the communities that we created as chosen family, and how in the face of hardship our stories in collective memory transform and ultimately prevail.

In contemporary film, I can see this effort to re-tell our stories and fill in the blanks with pride, in the work of filmmakers like Dee Rees. Rees has narrated Black queer love with a strong autobiographical influence, challenging the ways sapphic women are conventionally portrayed in mainstream media. In Latin America, short films such as Breakwater (Quebramar), by Cris Lyra and Caricia by David Montes Bernal, portray Black queer communities in Brazil and Mexico and show us how solidarity and care are fundamental to our well being.

Films like The Watermelon Woman invite us to engage and converse with our queerness in a plethora of contexts; as individuals, within our friend groups, and in local and global histories of sexual and gender diversity. It addresses the historic tensions between Black and white sapphic women, replicating the issues between Martha Page and Faith Richardson in Cheryl and Diana’s relationship. Rarely do we find lesbian films that stimulate our thoughts in this fashion AND remind us of how fun being queer people of color really is. While it tells the viewer of the systemic challenges we face, it doesn’t relish in showing graphic incarnations of this violence, focusing instead on the futures we are able to build collectively when we are able to portray the past of our own communities.

The importance of Cheryl Dunye’s film resides in her ability to speak to sapphic women like myself, that don’t feel seen by mainstream lesbian media. Even in Mexico, my country of origin, the most documented and popular sapphic histories are those of Frida Kahlo and Chavela Vargas — white women whose queer experience completely excludes Indigenous, Black, and Asian perspectives in our region. Just when I feared that there were no films that had my same concerns, nothing that spoke to my yearning for a story written by someone like me, The Watermelon Woman appeared like a beacon of light. Showing me that our stories matter, and most importantly — we have to right to tell them ourselves.

This is beautiful. I 100% agree that Cheryl Dunae completely shattered the expectation of what queer cinema can be.

“Yes, they represented what it was like to be a wlw, but they mostly centered the experiences of rich white women. The lives and experiences of those women were nothing like my own, even if we did share our sexual orientation —the way we moved through the world was drastically different. Those movies always left me unsatisfied, how was I supposed to relate to these tragic stories of white women desperately trying to hide their lesbian love affairs?”

YES love everything about this