This piece was originally published on 07/05/18.

George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020, and we stand in unequivocal support of the protests and uprisings that have swept the US since that day, and against the unconscionable violence of the police and US state. We can’t continue with business as usual, which includes celebrating Pride. This week, Autostraddle is suspending our regular schedule to focus on content related to this struggle, the fight against white supremacy and the fight for Black lives and Black futures. Instead, we’re publishing and re-highlighting work by and for Black queer and trans folks speaking to their experiences living under white supremacy and the carceral state, and work calling white people to material action.

Author’s Note (06/08/20): When I originally wrote this article’s predecessor three years ago, I thought we were already in crisis under the still-new presidency of Donald Trump. I know I was: I was fresh out of a stint in the psych ward, underemployed, and grasping at lifeline to survive. I found it through intentionally building community with other QTPOC, and they literally saved my life. Looking back, I was naive. My mental health has gotten better, but overall things have gotten so much worse. The lessons I learned, however, are still powerfully relevant—maybe even more so—as we’re now collectively struggling under the dual threats of the COVID-19 pandemic and an increasingly-fascist president’s callous, brutal response to cries for justice. Now more than ever we have to take care of each other. The increase in support for mutual aid projects is beautiful and heartening; the amount of allies donating and supporting their Black community members is incredible.

But this moment will fade, as the uprisings in Ferguson, Baltimore, and countless others further back in history did. There will be a COVID-19 vaccine, and cries for America to “return to normal” will increase until they are deafening. If we’re not careful, the interdependence and community-building we’ve had to rely on to survive the last couple months will fade as well. But we know that “normal” was not working for most of us. We have to build community alternatives to policing, we have to reject rugged individualism, we have to recognize the limits of “self-care.” And we have to start with ourselves.

This is a lightly-edited version of an article originally published two years ago, and isn’t specific to the crisis we find ourselves in today. It does not replace sustained political action to change the systems of oppression that operate in our society. But it is a supplement. We’re fighting a marathon battle against entrenched white supremacy and capitalism among other things, and building “community care” is a means to attempt to survive as we continue to live through this crisis, not as a way to solve it. The more we rely on each other, however, the less we need to rely on the State and its institutions. Please use this resource to the degree it works for you and your community.

Asking for help when we’re suffering is incredibly difficult. We’re taught to be self-reliant, to be rugged individualists, to take care of ourselves. Self-care ideology tends to reify, rather than challenge, this foundation of white Western culture. Mainstream self-care rhetoric can be ableist and alienating for marginalized folks, such as LGBTQI, disabled, and immigrant communities, low-income communities, and communities of color, who often don’t have access to the kinds of things self-care listicles usually suggest or the financial resources to take advantage of them. Capitalism and heteropatriarchy purposely isolate us—trapped in our homes, dependent on our “nuclear” families, too exhausted from working to organize or socialize with our neighbors—and in many of our cities, gentrification breaks up our communities even further.

There is an urgent political need, especially in Trump’s America, for marginalized folks to build support networks within our own communities, as the State (police, health care systems, immigration, schools, welfare systems, etc.) has never genuinely cared for or protected us and cannot be relied on. Those of us with disabilities, who require assistance, support, and care from others in order to survive, are in a difficult bind. We’re often left relying on the State, or on our significant others and biological family members for care. For many queer and trans people, significant others and family members are unavailable or overburdened by struggle themselves, and so we suffer alone.

Last year, I published an article here on Autostraddle laying out a critique of self-care rhetoric borne out of my own experience and envisioning what “community care” could like. Since then I’ve worked extensively to incorporate that vision into my personal life, and along the way I developed several tools and strategies to create and maintain community-based social networks built on deep, intimate friendships and centered on mutual aid and support. I’ve shared what I learned and developed in workshops at a number of conferences. This article is a brief overview of that workshop.

So what do we do? How do we take care of each other? Here’s a framework. It’s a continuous work in progress that can be adapted to a variety of communities and social networks and should be utilized to the degree that it works in your own community.

The main idea is two-pronged: first we must model in our own lives what we wish to see in community—that means, however scary and difficult, we have to teach ourselves how to ask for help. Second, we have to support our loved ones and community members to do the same. When we’ve all broken past the fear of being burdens on others, when we as communities learn how to ask for and give help and support, we’ll be able to take care of each other.

PART I: ASKING FOR HELP

- Figure out your needs

- Figure out your limitations and how community can help

- Ask for help

1. Figuring out your needs

What would your best, healthiest life look like? If your needs were met and you were thriving, what would your day-to-day look like? Or, if you’re currently struggling, what would it take to be well? Be aspirational. Don’t let yourself be cornered by your current job or financial situation. Write 3-5 “I” statements envisioning yourself living your best, healthiest life. What would that look like? For example, here are a couple of mine:

- I cook dinner for myself 3x per week

- I exercise 2-3x weekly

Your “I” statements might be more or less practical than mine—just try to make them as “SMART” as possible and as active as possible. For example, write down things you can do, rather than feelings or “I am…” statements (though if that’s where you want to go with it, go there!)

2a. Figuring out your limitations

What keeps you from doing those things, if you aren’t doing them already? What are your barriers? Are they physical, mental, emotional, spiritual? Mine are mostly mental and emotional barriers. I am able to do these things, but I don’t, for a variety of reasons. Write down what’s stopping you from doing those things already. For me, some major barriers are:

- Lack of accountability: I spend a lot of time alone, and have nobody to check me if I don’t do the things I commit to doing to take care of myself. If I tell even just one person about my plans, I’m much more likely to make them happen.

- Social anxiety: Being in crowded places with strangers is like my kryptonite, especially at places like the gym where my gender is really obvious, having a friend for support is essential.

2b. How can community support you?

Imagine that all of your friends and family, everyone in your community, wants you to live your best, healthiest life, and will do what they can to support you in breaking past those barriers. Well, you don’t have to imagine it—it’s likely true! One of the most remarkable things I realized when I started asking for help was that my community stepped up in incredible ways, and I found out, contrary to the stigma and rhetoric around being burdensome, that they enjoyed it! There were a bunch of people excited that I finally reached out, because they had been caring from afar but not knowing what to do or how to support. Take a look at the things you need and the barriers you have to making those things happen. How could a community member support you in overcoming those barriers?

For me, they were:

- Accountability calls/check ins: like, “go to bed bb!” or “hey, did you make any art this week? I want to see it!”

- Intentional Social Support: like, accompanying me to a party/event and committing to being on my arm the whole time so I don’t get anxious, or going to the gym with me so I’m not a trans person in the locker room alone.

- Crisis text support: like, when I’m having an anxiety attack (see an example in part 3, below).

3. Ask for help!

This is maybe the hardest part—but once you’ve figured out what you need, and how folks can support you, you need to ask them to! Here are some simple ways to do so:

- Individual asks: Since you know a bit better what you need after part 2b, who do you know who might be able to provide those things? Do you have a friend who works out a lot? Ask her if you can go to the gym together! Does one of your friends text constantly? Maybe she can be your text accountability partner! An example: When I was well, I realized that what I needed to hear in the moment when I was having a panic attack was three simple statements that I knew to be true, but couldn’t convince myself of in the moment of crisis. I asked a friend whether she’d be willing to text the three things to me at a moment’s notice. She gladly agreed, and has gotten me through a handful of panic attacks over the last couple years.

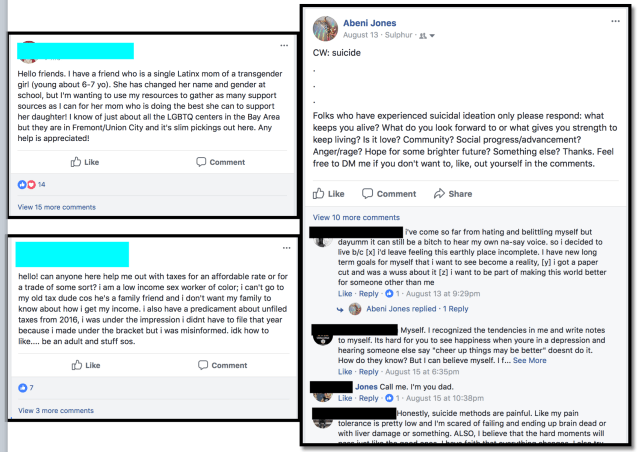

- Social Media: Facebook, Instagram, etc. can be super alienating or super community-building, depending on how you use them! For example, one of the things I needed as I recovered from my suicide attempt was advice and commiseration from folks who had been there. Facebook provided an opportunity for me to reach out for this kind of support, and it delivered! Facebook groups can be incredible community-building tools. For example, in almost every major city, there’s a “X City Queer Exchange.” I’ve utilized these Facebook groups in the Extended Bay Area, Seattle, and New Orleans, and all of them have been incredibly active and fruitful, both for giving and receiving support, to varying degrees.

- Intentional Conversations with trusted folks can be so helpful and necessary. There are different types of intentional conversations—advice, processing, and venting are the main three—at which different people excel. Ask your friends who have been through similar situations for advice about what to do. Ask your very emotionally adept and/or analytical friends for processing, which is when you try to better understand a situation by discussing its intricacies. And ask your friends who you know are good at listening without judgment to vent at them without their providing any feedback unless you specifically ask for it.

- Health Care: If you have access to it, getting mental (and physical!) health care is essential. Therapy can be key to survival. I find that my sessions with therapists are almost always “venting” sessions—I don’t need a stranger’s advice and rarely their processing, I just want to talk for an hour about my problems without feeling as though I’m taking up my loved one’s time or emotional energy. But therapists are paid to listen to your problems! Utilize them if you can, and make sure you look into it. Many of us think we can’t afford therapy, but there are sliding scale therapists, peer counselors, most colleges give a few free sessions with the campus health plan, and you can always barter emotional labor with members of your community.

- Is there an app for that?: NotOK is an app that facilitates the asking for help process. After a bit of work on the front end, when you’re not OK you can simply open the app and press a button and it texts your trusted contacts a short message informing them you’re not OK and shares your location! You can set this up yourself without an app, but the app makes it a bit easier.

Remember, when you ask for help, be specific. Ask for what you need (see part 2 above!). This helps you get your actual needs met and helps supporters know whether they can support you in the ways you need. It’s also important, however, to be flexible—for example, if you need a ride to the grocery store, but someone offers to pay your bus fare and/or accompany you and/or to help you carry your bags, consider whether that’s another way to get your needs met that you’re OK with. If the offer doesn’t meet your needs, though, it’s not disrespectful to thank them for the offer but decline it.

Asking for help is simple, but very difficult. It’s essential to set up structures for these types of support when you’re feeling OK and have the capacity. Set up the means for which to ask for help before you’re in a crisis moment—when you’re in crisis, it’ll be difficult to reach out for the first time or in a new way.

PART II: BUILDING A COMMUNITY OF CARE

Everyone has different capacity for different types of community-building. Some people can go out on the front lines and march, rally, and occupy spaces. Others can write articles, tweets, and posts, and stay all up in the comments and conversation and be a part of the discourse. Some of us can provide seemingly unlimited emotional labor for comrades and family, while others can do physical labor or can provide resources in other ways (financially, for example). It’s all necessary, and there’s no hierarchy here—we all get in where we fit in. It doesn’t have to be reciprocal and it doesn’t all have to be valued the same by society.

Figuring out where you fit in is key for Part II. In Part I, you figured out what you needed from community. In this section, you’ll figure out what you can offer community and how to build a culture of community care in your social network.

- What do you have to offer?

- Offer support when you can.

- Be open and intentional about the kind of community you’re trying to build.

1. What do you have to offer?

In Part I, you wrote down what you needed from your community members. Of the things you need, what could you also offer? Look back at your list of ways you would like to be supported. Which of those could you offer to others? Which couldn’t you? Write a star next to the ones you could also offer.

Analyze your resources. What do you have? Everyone has something: Large kitchen? EBT (food stamps)? A car? Extroversion? Money? Writing skills? Business skills? Empathy? Art skills and/or supplies? Multi-lingualism? A “fancy,” “official-looking” outfit? Carpentry skills? Some time? Any and all of these can be incredibly useful in supporting someone in community. What do you have to offer? Some of these seem esoteric, but can be incredibly helpful in ways you might not immediately expect.

A large kitchen can host an affinity group’s monthly meal, even if you’re not part of the affinity group. EBT can be a lifesaver; there are assuredly bunches of folks in your community who are food scarce and should qualify for EBT but aren’t on it for whatever reason; if you can spare a few veggies here and there it can literally save someone’s life. Cars are crucial, especially so depending on where you live. Grocery store carpools can change lives. Helping someone write a resume/cover letter can be the difference between them getting a job or not, and those are NOT skills most marginalized folks are taught in school! Multi-lingualism can also be a lifesaver—so many older folks who don’t have comprehensive business-level English skills have to rely exclusively on biological family in order to navigate the world. If a community member has a court date, doctor appointment, are buying a used car, or another appointment of some kind at an institution that will judge folks based on how they’re dressed or the like, having a person with them who can wield their class or race privilege in that situation (maybe that’s you in your suit or skirt, especially if you’re able to pass as older, whiter, and/or straighter than your community member) can really up their credibility.

2. Offer support when you can

Because it’s so hard (and culturally discouraged) to ask for help from community members, it’s hard to know how to go around supporting community with the resources you do have. As we build community care structures from the ground up, it’s going to be tough. Usually the best you can do is try to notice when people around you are struggling. Maybe it’s a vague Facebook comment, maybe over dinner or drinks a friend reveals something to you, maybe you read a local news article or see your neighbor dealing with something on your block. Or maybe you’ve seen what resources/privileges you have and just want to straight up offer them to community members in a local queer Facebook group. There are two key questions that you need to remember:

“How can I support you?”

If the person has done some introspection like we did in Part I, they might know exactly what they need, and by asking them this, you give them the freedom to let you know. However, because we aren’t taught how to do this, most of us don’t know what we need, especially from people in our extended community. When that’s the case, you have to be proactive:

“Would it be helpful if I ____?”

If your friend has no food and their car broke down so they can’t get to the grocery store, you can offer to give them a ride, or bus/Lyft fare, to send them delivery, or to come over and make a meal and eat it with them. Making a clear offer can really help when someone’s in crisis, because all they need to say is “yes” or “no,” they don’t have to figure out too much or negotiate anything, they can just accept or deny the support you’ve offered.

[Author’s note: Right now, asking Black community members “are you OK?” or “How are you holding up?” can be really upsetting and stressful. Please try offering support by using these questions; we probably want to lean on other Black people for emotional support right now. You can probably help best by offering material support].

Neither of these are perfect—what if, for example, when you ask how you can support someone, they ask for something that’s beyond your capacity (they need rent money, and you’re broke! Or they need a translator, but you’re monolingual)? Or, you have something to offer but it’s just not what they need?

By figuring out your capacity, you can make sure to only offer support that you have capacity to give, and by building community and knowing what other folks in the community have to offer, maybe you can make a suggestion for someone else who might be able to help. But as we build our skills of asking for and receiving support, we might need to be more explicit about what our capacities are so that we know who to go to for support in certain circumstances.

A tool like the Support Card below (and there’s a link to download a PDF at the end of this article), can help facilitate this. It might seem extra—well, it is extra—but if you’re looking to really do some work to build your community you might have to get a little extra. I recommend you use something like this with your inner circle, but a form of it can work with wider networks, too.

Take two copies of the Support Card, fill one out by circling what you have to offer, and then give it to a friend. Ask her to fill the other one and give it back to you. That way, you both know what each others’ capacities are. Imagine if everyone in your social network had a stack of support cards for all of their close friends and comrades so that, if they ever had a moment of crisis, they could analyze what they needed, then go through the support cards and find out exactly who to ask for help based on what each person’s capacities are. And they know this support is being offered, so it’s not as stressful to ask for help, and everyone else in the community is doing this too, so there’s less stigma. This can be done in a much less structured way, but for many of us, the structure takes some of the anxiety out of the process.

3. Communicate your vision

It’s one thing to model asking for help from your peers and community. But if you want to build a whole community that cares for each other, you’ll have to do a little work to empower the rest of your folks to break down the stigma around being a burden on others.

Sharing support cards with your close friends can be a good start. Just telling your friends how much you appreciate their care and support, and offering to be supportive of them in whatever ways you can, is also a good start! Reaching out and offering care when folks are struggling is key, as it shows that you’re not all talk but are really interested in backing it up.

By utilizing some of the tools I mentioned above, like social media, you can also take care of folks in your extended community. Sometimes offering a ride to a member of your queer community, for example, can lead to making a new friend. Giving away excess food instead of throwing it away can help a hungry person in your community and reduce waste. Donating or sharing a struggling person’s fundraiser can help them get the reach they need. When I was raising funds for my top surgery, the retweets from members of my extended community, many of whom knew the right hashtags that spread it even further, made all the difference.

Community tends to build outwards like ripples in a pond. You build a relationship of care and support with a couple close friends. They do the same with a couple of close friends. And then it keeps building and growing. Community building works best locally, and in-person—though social media and online communities can be a great facilitation tool. But if we’re talking about disability, and crisis, ideally you’ll have people locally who you can reach out to in the really difficult moments—folks who are nearby and can come through in person if they have the capacity.

This work is essential if we want to achieve liberation for all members of our community, not just the ones who can do self-care, the ones who have social capital, the ones who aren’t disabled, the ones who can rely on the government because they don’t have to fear being mistreated, discriminated against, or worse. This is also a political mission—the people who would prefer we not exist need us to be isolated and helpless in order to achieve our extermination. But by building community, and taking care of each other, we also build power to achieve liberation.

The final task is to put this all to work: think of 1-3 close friends with whom you’d like to build a deeper connection of care. Write 1-3 ideas of how you might do this—fill out and exchange support cards? Send a text offering care and support? Post on your local queer exchange offering rides, food, accompaniment, or something else? And … commit to making it happen! THIS WEEK! It’s never too late to get started, but it’s also never too soon.

Resources

- Beyond Self-Care Bubble Baths: A Vision for Community Care

- Download Support Card Here

- Purchase The Curriculum this is a part of by clicking or contacting me directly

- How to How to be an Ally to Sick People posted at Autistic Hoya

- Disability Justice Writing by Mia Mingus

- Living Index of Mutual Aid Resources by Autostraddle

- Big List Of Mutual Aid Resources by Mutual Aid Disaster Relief

- Big List Of Mutual Aid Resources by M4BL

- Big List Of Mutual Aid Resources by It’s Going Down

- Places to Donate And Support Protesters by Teen Vogue

- Places to Donate And Support Protesters by Rolling Stone

Abeni this is amazing and one of the reasons I love autostraddle and this community so much.

The way that you laid out everything so clearly and envisioned all people as needing care and capable of giving care in various capacities is so obvious but not often done. The steps and how you structured this whole piece made me reexamine the way that I ask for and give care.

Right now my main method of community care is childcare for the queer parents in my community but I could be doing more emotional processing work with pals who need it. Thank you so so much for this beautiful piece that I will def use as a resource! xoxoxo

I agree this is very helpful and affirming. I will have to start using would it be helpful if I_____ over what I have been currently using. The wording feels less pressuring, and more caring. I also like the part about using the privileges we have(or perceived to have) to help our friends.

Abeni, I didn’t get a chance to comment on Part 1, so I want to say now that your writing and teaching on this subject is terrific and feels *so* relevant to my life. Thank you!

I’m extremely glad I attended your workshop at camp, and I’m happy to see this article recapping what you talked about there. It’s also a helpful reminder of the goals I set for myself, what progress I’ve made so far, and the work I still need to do.

I’m also excited that you’re moving forward with the app – I hope that development process goes well!

This is an AMAZING resource!

This is a beautiful article, highly actionable, and highly useful. Thank you for taking the time to put this together.

Abeni, I have one request: I would appreciate if you coudl edit or remove the following line “This is also a political mission — the TERFs and xenophobes and fascists and conservatives and capitalists and all the rest who would prefer we not exist need us to be isolated and helpless in order to achieve our extermination.”

Some of the people in my network who most need care identify as conservative, or support capitalist ideologies (implicitly or explicitly). There are two reasons I ask it be changed. The first reason is that I want to send this article to those people to read, and to continue my work to help them, but I know as soon as they see this line they will feel attacked and dismiss the rest of the (fantastic) advice.

The second reason is that many of the people that most need our help and care are early in their journeys of progressive politics. Some will never be able to begin that journey until they receive the care they need to stabilize their situation, and many people subscribe to destructive ideologies when they aren’t getting the care or connection they need, and are looking for someone to blame.

If someone feels they do not want to do the work of caring for those of ideologies who run contrary to theirs (or threaten their safety, life, livelihood, etc.), that is a completely valid choice and I support that. But as someone who has a bit more privilege (white, cis, financially stable, educated), I have and will continue to do the work of reaching across the divide, and I’ve found that many folks across the divide need a lot of help. Perhaps one of the best of achievements of my life was converting an American ex from a staunch republican position deeply rooted in racism and misogyny to voting for Hillary. However, this change in views came after two years of my influence and care, AFTER the rest of the work: helping her to feel safe and worthy, recover from trauma, encourage her agency over her own mental health and stability, and help her seek help from others. It could not have happened before that work was done. If changing her views was a precondition of my support, there’s no way we ever would’ve gotten there.

Thanks for considering.

word! makes sense. will edit in some fashion soon :)

Done! ☺️

Thank you! Still a very important message, and you communicated it so well :)

@queer_girl can this still get a comment award or go in a hall of fame for a beautiful ‘could you please change this for a reason related to identity/beliefs’ exchange? Thanks Abeni and westwood!!!

Hi Abeni!

Thank you so much for this article. I just wanted to make a small but important correction — at the end, you cited as a resource an article on my blog, Autistic Hoya. The article “How to be an Ally to Sick People” was written by a good friend of mine who asked me to guest post it anonymously. I think it says that on the article page itself, but I want to make sure I’m not being credited for something I didn’t write. Thank you again.

Oops thank you! I’ll fix it ASAP ☺️

Abeni! This is so smart and helpful. Systems and processes help me manage my anxiety and depression and I’m going to print this out and get to work. Thanks for acknowledging that learning to ask for help is real work but so so worth it.

This is so concrete! Going to take some time to think with it this weekend.

Wow this is so amazing! Thank you for sharing this!! I really wanted to go to your workshop during camp but it conflicted with something else. So glad you are doing this work and sharing it <3

Wow. I’m going to come back to this a lot of times. Thank you!

“There are different types of intentional conversations — advice, processing, and venting are the main three” – YES SO FUN to see this written down!!!

I keep coming back to this & also want to have my friends do a study group on it.

This resonates in very cool ways with Emergent Strategy by adrienne maree brown which I recommend to anyone and everyone about surviving and thriving (as individual, community, organization) in this time.

Thank you so much for updating this Abeni!