Welcome to Hidden Gems of Queer Lit! This column is for those of you who found the first reflections of your desires in a dusty corner of the library, and for those of you who know that important histories and new ways of looking at the world are nestled in yellowed pages as well as flickering screens. Every two weeks I’ll profile a queer lit title that’s outside of the public eye for one reason or another: obscure, small-press, older, aimed at a different niche, or otherwise underrated. It’s my hope that you’ll connect with some of these books and treasure them as I have.

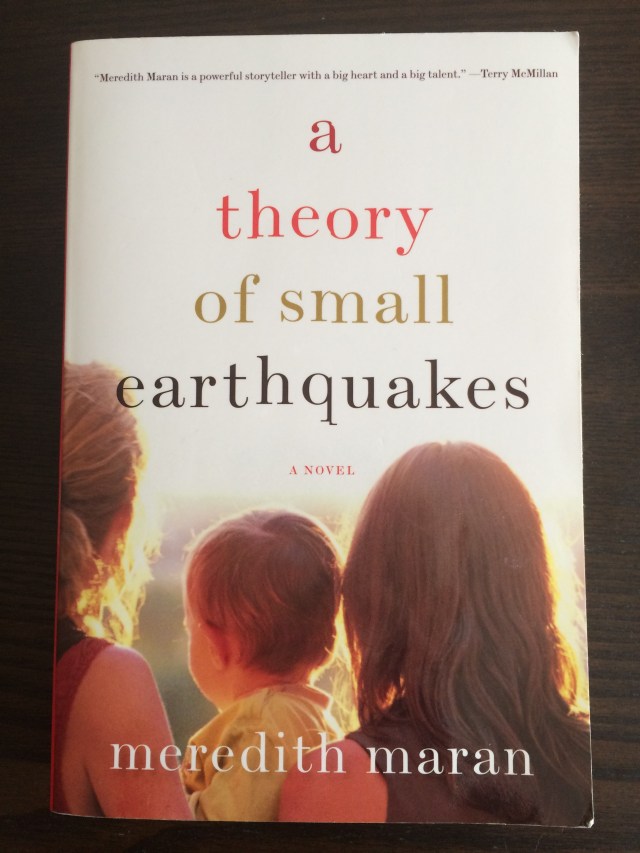

When acclaimed journalist and nonfiction writer Meredith Maran chose the cover of her first novel, she selected a sunny image of two women and a baby, lending the book a beach-read feel. It was a good decision, as it led a wider audience to pick up A Theory of Small Earthquakes: a novel about bisexuality, family, and secrets, with a narrative that’s quite different from the typical work of women’s fiction.

The book begins in 1983 with orphaned Alison in college, cringing at the overzealous feminism of her women’s studies professor. She bonds with a bright, androgynous classmate named Zoe, an artist who likes her student journalism and wears fabulous outfits of “orange and lime green, polka dots and stripes, crumpled linen and corduroy and velour.” Soon Alison has a new friend… until Zoe asks to kiss her. Their relationship is idyllic at first, with self-critical Alison finally feeling accepted and nurtured: “Zoe’s love felt like a prize Alison had won without knowing exactly how or why.” Zoe and Alison move to a cottage in Berkeley, where Zoe paints and Alison takes up a writing career. But there’s a fissure in their blissful domesticity: both women want to have kids, but Alison longs to have a family the “normal way.” Thus begins a drama of paternity secrets and deliberately constructed family.

The novel has an interesting take on bisexuality and the differences between the worlds of same-sex and opposite-sex relationships. Six years into her relationship with Zoe, Alison feels a stark disconnect with the politicized, feminist queer community that her partner has increasingly embraced. She has femme invisibility to contend with: “A couple of heavily tattooed women in men’s work clothes walked by, glanced at Alison blankly, cruised Zoe blatantly, and swaggered inside.” She’s also unnerved by Zoe’s confidence in being out: “Alison was always begging Zoe not to draw attention to them in public. But Zoe just went on living as if the world were already the way they wanted it to be.” Despite her misgivings, her love for Zoe isn’t going anywhere, and the flamboyant artist pushes Alison to become her best self.

However, complications arise when Alison gets pregnant and the cause is unclear: laborious fertility treatments with Zoe, or an impulsive one-night stand with her editor, Mark. For Alison, already feeling the cracks in her relationship, Mark promises the stability that she craves. Where Zoe is both devoted and demanding, Mark is earnest and easygoing. Soon Alison and Mark are raising her son, Corey. Alison initially finds motherhood blissful: “She didn’t have to try to love Corey fully, the way she’d struggled to love Zoe, the way she still struggled to love Mark. Every time she looked at her baby, smelled him, caressed his feathery head, her heart bloomed, a cactus flower unfurling in her chest.” However, the competing demands of career and family become a lot for Alison to handle, and Zoe steps in as caretaker. An unusual sort of family is formed.

Maran handles the differences between Alison’s two relationships sensitively, and acknowledges the shock of shifting from one type of relationship, sex life, and social status to another that’s equally desirable but drastically different. Some might read in a cringe-worthy implication that bisexuals like Alison “need both a man and a woman to be happy,” but there’s something subtler than that going on, and I appreciate the novel’s acknowledgement that families can take many forms other than the nuclear norm. As Alison discovers that her seemingly simpler relationship with Mark requires the same emotional commitment she feared to make with Zoe, and as she witnesses same-sex relationships becoming more accepted in her world, Alison — and the reader — can’t help but wonder if this story would have had a different ending in a different time.

Maran’s depictions of Berkeley and its political climate across the ’90s and early 2000s are delightful. “The town was like a living museum of the sixties, populated by idealists frozen in time… The front yards she passed were unfenced, unfettered by design; they looked like they’d been planted by Dr. Seuss. Purple-blossomed princess trees, shocking pink impatiens, Day-Glo orange nasturtiums bloomed in madcap profusion amid rusty metal sculptures, toilets sprouting red geraniums, towering papier-mâché peace signs.” Her characters and their struggles are sympathetically drawn, and while there are moments they don’t seem entirely believable, they’re definitely worth knowing.

This sounds really interesting! I’m going to read it. Thank you!

I am hesitant about the bisexual content, things that aren’t bad in their own right, but are tropes used so often: cheating on a woman with a man, settling down with a man after dating women, more in the closet than gay characters.

But then again I am starved for fiction with bisexual characters, so I might give it a try.

I checked out the book on goodreads, and haha, one woman gave it a one star rating because she was tired of the “Bush bashing” in the book and “didn’t appreciate being described as not bright since [she] voted for Bush (both times).” This is pretty much a recommendation for the book for me, probably not what she intended.