I tend to roll my eyes when corporations market to the queer community because it’s usually empty pandering, often accompanied by back door donations to anti-LGBTQ+ conservatives. And while I still believe that, I was reminded recently that these advertisements — and all the hype around them — can speak volumes about the state of LGBTQ+ rights in a given place.

Remember the Hallmark commercial from 2019? The wedding registry site, Zola (owned by Hallmark), aired an ad featuring a lesbian wedding. Conservatives lost their shit and waged a campaign against the commercial for being a desecration of marriage, especially because the two women kiss at the end. Hallmark’s TV Chief decided to take the ad off air. After mounting pressure from GLAAD, countless celebrities and a public boycott campaign against Hallmark, the company issued an apology for pulling the commercial. A month later, that TV Chief stepped down in recognition of his huge mistake in the whole debacle.

To be perfectly honest, I didn’t think much of the whole thing. In fact, I was traveling at the time and only heard echoes of what happened weeks after it all unfolded. But when history seemed to repeat itself in India at the end of October, I couldn’t help but think back to the Hallmark mess and see the clear parallels and, also, the substantial divergences.

Dabur, an Indian brand that sells health and beauty products, aired a commercial for a skin-bleaching cream featuring a lesbian couple celebrating the Hindu holiday Karwa Chauth. The advertisement raised a lot of questions on all sides. On the left, progressives, feminists and LGBTQ+ activists took issue with the advertisement for its coloristic promotion of skin-bleaching and its celebration of a deeply misogynistic festival. But, the backlash from the Hindu ultraright was swift and unrelenting. Ultimately, Dabur buckled to pressure from the ruling Hindu nationalists, pulling the ad and issuing an “unconditional” apology.

Hallmark and Dabur. These two incidents started out similarly and yet the outcomes couldn’t be more different. And if this were just a story of a corporation with a poorly-conceived attempt at pro-LGBTQ+ messaging, I wouldn’t be writing about it. But there are so many layers to unpack here, starting with the details of the commercial itself, and each layer reveals something different about the political situation in India.

The emotional thrust of the advertisement — and also the heart of the controversy — is the fact that two women are holding the Karwa Chauth fast for each other. To fully appreciate what Dabur was trying to do and what the Hindu right rallied against, you need to know what Karwa Chauth is.

Growing up, my knowledge of Hindu holidays was limited and based largely on observation. The theme generally seemed to be that women must celebrate, honor and worship the men in their lives: fathers, brothers and, most of all, husbands. Karwa Chauth was, perhaps, the epitome of this. My mother would rise before dawn to start an all-day fast of food and water that she would only break at moonrise. My father would go about his day as per usual. I don’t recall seeing my parents enact the climax of the ceremony — emotions, most of all love, being nonexistent in my family, after all.

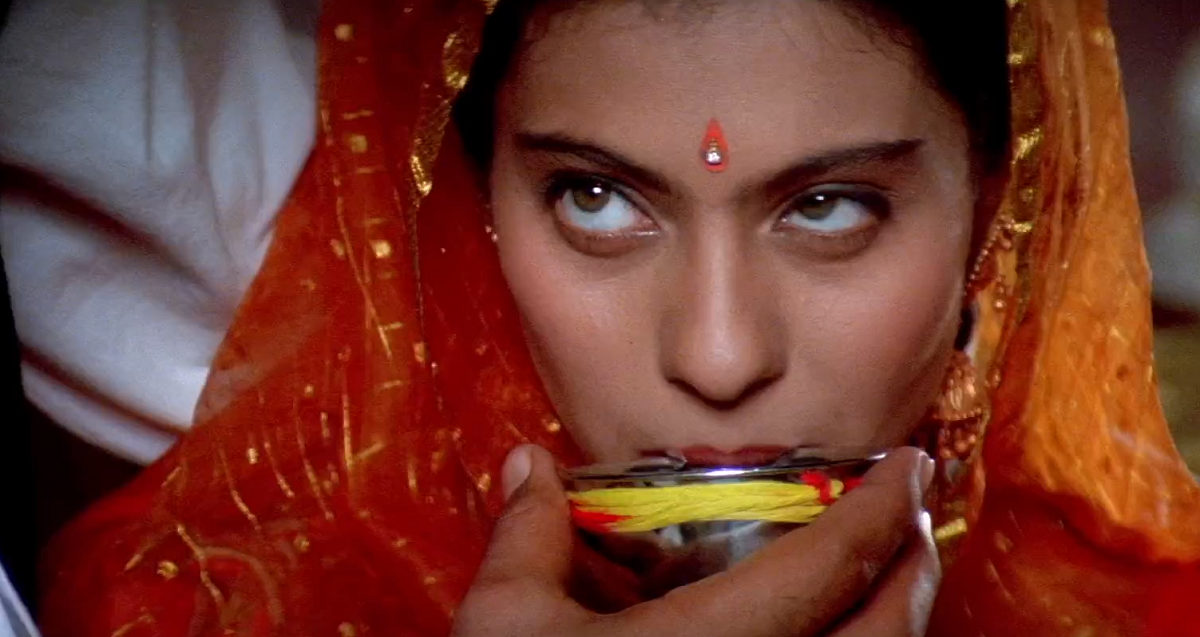

Bollywood filled in that gap for me. One of the key moments in probably the most enduringly popular movie of the ’90s, Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, is when the heroine Simran holds the Karwa Chauth fast. Her family thinks she is fasting for the man they expect her to marry, Kuljeet, but she subverts the rituals to be true to her own love, Raj. Once the moon appears, the wife (or, in this case, bride-to-be), looks at the moon through a sieve before turning to her husband. The husband then gives his wife her first sip of water of the day. In the most dramatic telling, the wife also breaks her fast by being fed by her husband. In DDLJ, just as Kuljeet is handing Simran water, she pretends to faint and is caught by Raj who offers the water to her instead. Simran winks at Raj to emphasize the symbolism of the moment for him and the audience alike: the sanctity of their secret relationship is preserved.

I learned the point of Karwa Chauth years after the fact: the belief is that wives fast for the longevity of their husbands. Wives must sacrifice at all costs for their husbands.

Some modern takes on Karwa Chauth have attempted to blunt the misogyny. Returning to DDLJ, for instance, Simran refuses to break her fast until she can eat with Raj, but Raj is being detained by family at the celebration. When he finally manages to sneak away, she scolds him, saying that he must have been stuffing his face while she was dying of hunger. Simran’s sister reveals, though, that Raj, a true modern gentleman, has actually been fasting all day too, for Simran. This perspective isn’t unique just to Bollywood. While many Indians have decried Karwa Chauth altogether, others celebrate it as couples, participating in the ritual fast of their own agency and as a sign of their love.

The other side of modernity, of course, is consumerism. There is a booming industry around Karwa Chauth, with the sale of cosmetics, henna, clothes, designer sieves and even phone apps being marketed to women.

And this is precisely where Dabur’s ad fits in.

While I might not personally agree that a custom like Karwa Chauth can be reinterpreted to have a place in a feminist worldview, I have to believe this is what Dabur had in mind when they created their ill-fated ad.

In fact, as the two women are getting ready for the ceremony, they ask each other why they’re holding such a difficult fast. “For their happiness. And you?” one woman says, using ambiguous pronouns in her response that don’t reveal the gender of her partner. “For their long life,” the first woman replies, similarly ambiguous. Hindi is a heavily gendered language, but it’s possible to refer to someone using formal pronouns that would not reveal gender, which is how the women are referring to their partners. That same level of formality is often used by wives to speak with and speak of their husbands, especially in the most traditional settings.

The ad pulls off a bit of subversion beyond the linguistic usage. In the first portion, the viewer is led to believe that these two women are getting ready to celebrate Karwa Chauth together socially for their respective husbands. When a mother-in-law appears, commending them for their “impressive preparations” and hands them their outfits, we think that maybe the two are sisters-in-law living in the same household. It’s only when the ceremony unfolds, and we see the two women turn to look at each other that the true nature of their relationship becomes clear. These women aren’t just together, they are married, and their marriage has religious underpinnings. In a country where gay marriage is still illegal, the political and social ramifications of such a representation really can’t be overstated.

In this respect, the Dabur and Hallmark ads share much in common. Both are subverting and reimaging marriage to be inclusive of queer relationships, specifically, between two women. They’re also normalizing queer relationships and affording them the same social legitimacy as heterosexual relationships by placing two women at the center of customs and traditions typically reserved for heterosexual couples.

But what exactly is Dabur selling in its supposedly woman-empowering advertisement? Skin bleaching cream. There’s a sick irony to marketing harmful and coloristic so-called “beauty” products to women in an advertisement that is seeking to subvert misogynistic gender norms and depict women’s agency in their relationships. And this is what makes it so difficult for Indian feminists and the LGBTQ+ community to wholeheartedly support Dabur’s ad the way many comparable American groups did for the Hallmark ad. Hallmark was being equally consumerist by marketing Zola, the wedding registry site, but it wasn’t marketing a blatantly racist product that upholds a narrow and sexist view of “beauty.”

As an atheist who was raised Hindu, I hate the idea of Karwa Chauth and everything it stands for, modern rebranding be damned. I have spent the larger part of my life in defiance of the notion that love is entirely about the sacrifice of women. So it’s easy for me to write off the whole thing as a company that made an especially poorly-conceived attempt to pander to the LGBTQ+ community. And so I largely agree with journalist Sandip Roy, who sums up the issue by saying:

“The Dabur ad tries to queer two topics that are viewed with disdain by many who consider themselves socially progressive — Karwachauth and [skin-bleaching] creams. … Do some rainbow sprinkles somehow radically reinvent our obsession with fairness and the long lives of husbands (but not wives)?”

But I also recognize the very real tension for the Indian LGBTQ+ community and particularly for women in that community. As the Instagram account for the #IWillGoOut movement to end street harassment in India put it:

“I’m more than happy to see a queer couple in love on the national digital space, with a happy mother in law standing by them. Instead of the usual problematic queer representation, we now have a lovely queer representation in a very problematic ad. Ugh. Progress? Who knows. Progress within a patriarchal space is still infected by patriarchy after all. But I know many queer couples urgently need to be able to imagine possibilities of safety, love, hope and home. Until better desi queer visuals come along, this problematic ad will do.”

Beneath it all, there’s a peddling of a particular narrative of Hinduism and India. Karwa Chauth isn’t universally practiced by Hindus in India, but looking at mainstream Indian media you wouldn’t know that. So many Bollywood movies and even made-for-streaming shows center this celebration, from DDLJ to another beloved Bollywood classic Khabi Khushi Khabie Gham to the recent Netflix show Bombay Begums. And, while the big Hindu holidays like Holi, Diwali and Karwa Chauth are seemingly inescapable in mainstream Indian media, the country with the third largest Muslim population in the world offers, at best, a much more barebones acknowledgement of major Muslim holidays like Eid.

Despite being such an unabashed promotion of Hinduism, for India’s Hindu right the fact that Dabur’s ad deviates from Hindutva is what’s really at stake here. While those of us on the left are conflicted over the ad for what it’s selling and how it’s selling it, Hindu nationalists (who hold power both nationally and in many state governments through the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP) are enraged because, to them, the idea of two Hindu women in a religiously sanctioned relationship is an unequivocal desecration of Hinduism itself.

Whereas the campaign against the Hallmark ad was led by the ultraconservative website One Million Moms and its social media pages, BJP politicians themselves stepped into the fray against Dabur. The ad was pulled after the Home Minister of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh threatened legal action against Dabur. While the hubbub around Hallmark died down after the company issued an apology for pulling the ad in the first place, Dabur, posted to Twitter that the company “unconditionally apologize[s] for unintentionally hurting people’s sentiments” (emphasis added) and removed the advertisement from its social media.

Journalist Sandip Roy offers some context for Dabur’s ad, which was only the latest foray by an Indian corporation into social issues that are seen as anathema by the BJP. Most of the previous ads created controversy for testing Hindu nationalists’ tolerance of Muslims or anything they view as remotely Muslim-adjacent, even when it isn’t. This is, sadly, unsurprising in India’s current hyper-Islamophobic political environment. One jewelry ad from 2020 delved directly into India’s Islamophobic political debates by showing an interfaith marriage. Shortly after the ad was pulled, India’s most populous state, Uttar Pardesh, passed a law (that had been under discussion for over a year) criminalizing interfaith marriages. Reflecting on all this, Roy observes: “Until now, though, LGBT issues had been a safer and less controversial place to exhibit liberal values rather than religion.” And the recent controversy around an ad that challenged the Hindu marital tradition of kanyadaan, or giving away of a daughter to the groom’s family, would seem to reinforce his thesis.

I would argue that it becomes impossible to really talk about LGBTQ+ rights without delving into religion because religions the world over have long called us sinners. This is as true in America as it is in India, as true of Christianity as it is of Hinduism.

I would argue that it becomes impossible to really talk about LGBTQ+ rights without delving into religion because religions the world over have long called us sinners. This is as true in America as it is in India, as true of Christianity as it is of Hinduism, even before we get into Victorian sensibilities and the legacy of two hundred years of British colonialism. Roy gives the example of two pro-LGBTQ+ Indian ads that didn’t evoke the kind of controversy the Dabur ad did, but neither of these ads made the mistake of explicitly placing LGBTQ+ people inside rituals that are entirely designed to exclude us. (As an aside, one of them is an incredibly touching trans-inclusive ad by a jewelry company and shows a trans woman getting ready for her wedding. But the ad doesn’t actually show the wedding ceremony itself, which, in my view, is at least partly why it didn’t draw as much negative publicity as the Dabur ad.)

At its core, rightwing backlash against Hallmark and Dabur were both about, more or less, the same thing: an insistence that queer people should have no place in the world. But the difference in the outcomes indicates that the fights for LGBTQ+ rights are in very, very different stages in these two respective countries and societies. America is not, by any means, a bastion of equality, and it has been three years since Section 377 was struck down in India, decriminalizing homosexuality. Yet I struggle to shake the sense that among Indians, being queer remains something to hide and is a cause for shame. In an attempt to challenge that view in the mainstream, Dabur made an ad celebrating a fundamentally misogynistic festival to sell coloristic beauty standards to women. But the fierce outcry was against the notion of a happily married lesbian couple, instead.

And that has only served to reinforce my view.

That was a fantastic article Himani! Thank you for providing all of the background information to put this in perspective.

Thanks so much for reading! I’m glad you found it interesting!

Thank you for this article. In India do the people in these ads get backlash too? Like is it harder for them to another roll cause they played an LGBTQ character or is most of the right wight backlash against the companies?

Thanks so much for reading! I actually don’t know the answer to your question. But I’m guessing not bc there have been a few Bollywood movies with queer characters who have been played by (essentially) mainstream Bollywood actors. I really think the anger here is because of the placement of queer women within an explicitly Hindu religious context, which is a decision the company made and so as far as I know the anger was directed towards Dabur. But I’m not the most active on social media, I can’t actually read Hindi which limits the amount of Indian content I have access to and a lot of content passes through Whatsapp specifically, so I can’t say for sure.

This is an incredible article. I don’t know much about LGBT rights in India and I’m fascinated (and sad) to learn more. Thank you so much for writing it

And this bit: I would argue that it becomes impossible to really talk about LGBTQ+ rights without delving into religion because religions the world over have long called us sinners.

When I read this out loud, I actually shouted YES to my housemate. Exactly. In my country (neither America nor India) homophobia has historically been based in religion, most religious people are homophobic and most of the homophobic logic, arguments and reasoning people use against queers of all stripes is ridiculous. Yes, individuals can be homophobic without being religious or religious without being homophobic: but that doesn’t mean that homophobia doesn’t have its roots, directly or indirectly, in religion.

Sometimes people in my country think that you can engage with religion without recognising or engaging with its long, long history of homophobia and misogyny, and that religious leaders and believers can be excused from their current homophobic or misogynistic beliefs. I don’t think there is any excuse for these, and I think religious people should be held to the same standards as everyone else.

Religious – not ridiculous! Though it is also ridiculous. I need to start proofreading before I post 🤣

Thanks so much for reading and I’m glad the article resonated with you! “Sometimes people in my country think that you can engage with religion without recognising or engaging with its long, long history of homophobia and misogyny” — I resonate with this SO strongly!

This was a really great piece, Himani. I know about Holi and Diwali but didn’t know much about Karwa Chauth so I learned a lot.

<3

Thank you for this thoughtful article, really appreciate getting to understand this more.

Thanks so much for reading!

My dad always held the fast with my mom and I grew up in the US so I guess I never grew up connecting it with patriarchy, but I also grew up in a household that wasn’t super religious in general but I never made that connection with the religion informing culture until you pointed it out how they can’t exist without each other. It gives a ton of context to my parents reaction to me coming out

Hi! Thanks for reading and for sharing your experience! As with every religious tradition, people’s lived practices can vary so much. My family is quite conservative and quite religious and sometimes I forget how much variation there can be, even among Hindus who might be coming from similar traditions and customs. So I really do appreciate what you’ve shared!

I might be reading incorrectly into what you’ve written but it seems that perhaps you faced some sort of resistance when you came out to your parents? If so, I’m very sorry to hear that. Wishing you all the best!

Such a good piece, thank you!

Thank you! And thank you for reading!

wondering if caste plays any role in this? similar to the way religion and class combine to subjugate women and men of color along with lgbtqia folx in the u.s.? specifically by defaulting white heterosexual maleness. i know u.s. class status isn’t analog to caste, but i can’t think of something that’s a better correlative. the presumptive default seems similar here, especially in the way that it encourages institutional/structural backlash.

the other thing i started considering after reading this is how insidious religious school systems are. if you look at the value of providing education, it’s easy the forget them as a tool of indoctrination. the tangent here is based on your discussion of the parallel to british colonialism. whereas education focused on knowledge is often a precursor to tolerance which is a precursor to acceptance, agenda-based pedagogy is a subversion.

thank you for the thoughtful discourse (again), Himani.

Hmm so I might not be understanding exactly what you’re referring to when you talk about the interaction of class, race and sexuality in the US. But when it comes to India this is actually quite complicated I think. My understanding is that there has historically been a non acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community regardless of caste or maybe you can say across caste lines. Based on some of the things I’ve read before section 377 was ruled unconstitutional threatening to out somebody was a way of basically blackmailing them and that seems like it was a fairly universal experience among the queer community in India from what I’ve read. Of course I can’t speak from personal experience because I did not grow up or live in India as an adult.

When it comes to the BJP though, caste is something that is very strongly enforced. So you can read all these horrifying articles online about people getting beaten by mobs or threatened etc because of caste issues. A lot of this is tied to religion too right? So for instance one of the things that I recall happening I think a couple of years ago that seemed fairly common was a low caste people who are responsible for handling waste and carcasses and things getting beaten by mobs of non-low caste people for handling cow carcasses for instance (even though that’s literally their job…)

When it comes to this advertisement in particular by all the cues that I can read these women and their families are not coming from low caste backgrounds. But even if they had been, I’m not sure the response to this ad would have been any different.

The other way in which I guess the caste system is at play here though as we’re talking about marriage right? So the caste system is intrinsically intertwined with marriage. The whole reason for arranged marriages and why marriage is so controlled in a traditional Hindu context is because it’s about maintaining the purity of the caste bloodlines basically. So looked at that way people who make their own choices in marriage, which is not just limited to LGBTQ+ people, are a direct threat to the caste system, and that in and of itself is a huge source of tension both in media and politics and also in families. In this respect it feels fundamentally quite different to me than class in the US or Western context.

Oh and to your other point, so I think you’re right about indoctrination through education. I think that’s something that happens pretty universally in the world including in the US. And it’s interesting how you say about religious school systems because from my view even public schools in India are fundamentally religious in nature right? (Actually, that’s also probably true more broadly as well)

But to the point about colonialism, so I didn’t want to get bogged down in this in the article, but the reason why I brought that up is because there is a line of thinking among queer South Asians where homophobia is rooted to colonialism and based on the things I’ve read I think that that’s a bit of a narrow understanding of the history of homophobia on the South Asian subcontinent. The irony is that the BJP see themselves as returning India to its pre-colonial era by enforcing such strong Hindu norms. And this is partially why I personally bristle against the idea that the British are solely to blame for homophobia in South Asian communities because they created the Indian penal code that had section 377 in the first place because Hindu nationalists are clearly equally homophobic.

himani one thing i appreciate about you and your writing is that you don’t simplify complicated things!!! so my mom’s dad is punjabi and she and i both grew up here, but we both have been a ‘pause?’ (well she’s more like exccuuuuuuse meeeee) about simplified narratives about queerness in pre-british-colonial india. my sense is that british rule took advantage of and intensified patriarchy, colorism, caste, landlording etc aaand in their violent pursuit to control every acre and human the british also (more) violently restricted the different societies, practices, and belief systems that lived in the pockets and margins of pre-british empires, and some of those pockets and margins had space for what we now understand to be queerness. but battling homophobia and exotification and white supremacy and and and makes it hard to hold all that, and i think you do a wonderful job.

here as in the US/ occupied turtle island

i really appreciate the distinctions and thoughtful discourse, @himani / @devney. somehow i always look for parallels to understand that which is different from my experience/exposure, even though the contrasts are what usually illuminates.

my initial, clumsy point was interrogating how social status is dis/similar to motivating backlash against alphabexual communities. each of your comments have been a wonderful opportunity learn more about the complex intersections of religion, politics, and social mores as distinct from that to which i am familiar. i’m grateful for time you’ve each taken.

ahh thanks for sharing this @devney! My father is also Punjabi and my mother comes from a rural-ish part of North India, so yea I’m totally with your mom on the “excuuuse me” response to simple narratives about pre-colonial India. I think your summary of the situation is right and aligns with some of the things I’ve read and thought about as well. Also, after being colonized for 200+ years, it’s kind of impossible to know what was the precolonial state of things, especially with the destruction of so much history and heritage, at the hands of the British and otherwise. In my least generous moments, my personal take on this is that, even if we do assume that Indians internalized British values after 200 years of colonized, it doesn’t really matter whether those values originally came from the British or not because the fact remains that those values are alive and well in modern India today.

Oh and @msanon– thanks for asking this question, it was definitely a thoughtful and worthwhile one!

thank you for linking to the bhima jewelery ad – soooo lovely (https://www.thenewsminute.com/article/bhima-ad-featuring-trans-woman-goes-viral-meaningful-dialogue-or-smart-branding-147378)

Yea, that ad was so so lovely!

Awesome that people pay attention to inclusiveness in commercials. This practice gets more and more widespread invalidating intolerant ads fully.