A few days before my father died, bewildered by brain cancer he asked me, was I happy? Yes, I said. Of course I’m happy. We say these things without thinking. Happy. I have no idea what this word means. Nobody knows what this word means.

Less than a year later, on the cusp of my 30th birthday, the person who would become my abuser bit my face on our first date — hard, and without cause or warning — and I did nothing.

But my body was begging me to listen. I found myself clenching my jaw and gritting my teeth when she tried to kiss me. I couldn’t stand the way she smelled. And when she left, I tore the sheets off my bed and I swore I would never see her again. But within days, I found myself revising every warning, overriding every instinct. I’d been numb for so long and, compounded by the death of my father, I was so estranged from myself that without even realizing it, I had mistaken the warnings for a challenge. I ignored the storm of dread inside my body. That’s fucked up!

The repulsion I felt was a distress call, but the distance at which I kept my heart from my grief meant that I couldn’t translate it. I had been stuck in those final moments of my father’s life; the MRI, the confusion, the are you happy?, the death rattle, the blue jays swarming the tree outside after his last breath, and my fruitless attempts to not feel any of it.

I had spent the previous two years watching brain cancer steal my father away bit by bit, but I hadn’t even begun to touch my grief. I showed up to that date thinking that I was okay, so much so, that I let a person I had just met viciously bite my face, and ignored the warnings from the purest, most animal part of my body. That moment has haunted me for a decade.

As a child, I don’t think I had ever seen an adult grieve openly. It seemed like something you were supposed to hide from other people — an indulgent, shameful thing. Weak. When I was 11, a group of my classmates dared me to cry as they bullied me, and when I finally broke down, they celebrated. And again at the age of 17, when I had my heart broken for the first time and I was so wildly and uncontrollably hurt and sad that it made the people around me uncomfortable. I saw how grief had the power to unravel me and it scared me. It wasn’t just weak — it was dangerous.

I carried this into adulthood and over time, my resistance to sadness and tears began to shrink my capacity to feel any kind of complexity in my emotions. As a result, I stopped learning how to differentiate between shame and hurt, love and desire, grief and ambivalence. Everything was muted. Lukewarm. Beige. I was okay, all the time. In order to avoid big outbursts, I would choose peace at all costs. Because of this, I became very easy to take advantage of.

And then suddenly, my father was dying, but the path to my most vulnerable parts had long overgrown. I didn’t know what to do — I couldn’t explain how I felt because I didn’t even know how I felt. I think about the person I was 10 years ago and I wish I would have taken the time to tend to the loss of my father in misery, in loneliness, in numbness, on a dance floor, in the dark, in community, in therapy.

This is why we have a responsibility to grieve. We have a responsibility to feel the too-muchness of the lack of a person. We owe it to ourselves to fall apart, to come completely undone. The unthinkable can and will happen, but sorrow and loss are only splinters of what we can handle. The ritual is in the remembering.

I still remember everything about that first date with my abuser; the bite, the repulsion, the dread. Everything. And even though I got free and I’m here now, the root of that pain still tells me that I wouldn’t have survived if I had stayed. I still remember my father dying. The remembering hurts me; it’s excruciating. It’s sad. But that sadness also reminds me of the time I saw my father dancing alone in the hallway on Christmas Eve with his eyes closed, smiling. I had a father who loved me enough that, even as his body betrayed him, he still needed to know if I was happy.

I did not take my life seriously until someone tried to take it away from me. And even then, I did not take my pain seriously until I learned to trust that grief promises more than just the unrelenting whimper of don’t go, don’t go, don’t go. Grief asks us only to feel it, and in return, it offers us the possibility to feel everything more.

Around the closing of summer this year, I was driving in the country just before sunset, listening to Lovers in a Dangerous Time, written by Bruce Cockburn in 1984. It’s a song that was adopted by a generation of queers and trans people as they were dying en masse at the hands of an unrelenting and largely ignored AIDS epidemic. A generation who, in the face of what must have felt like their extinction, loved and fucked and cared for one another through it all. I thought about those who have survived and have carried those shattering losses every day for 40 years. We have so much to learn from them about the power of holding grief and joy in the same hand.

I burst into tears. For a moment, I felt that familiar panic try to take control and shame me back into that old, beige numbness. But the breeze was warm, and I could see each and every tree that made up the forest around me, peacocking in their own delicious shades of juniper, pine, emerald, moss. I wasn’t just grieving, I was feeling.

This is what grief promises. It guides us out of the dark by moving through it, not away from it. It’s a seed that roots deeper into the ground while it pushes up to break through the surface of the earth. It relies on both the dark and the light until it’s no longer a seed — it’s not even a tree — it’s the forest. What better way to honour my younger self, our queer elders, my father, than to cry until I choke because everything feels just so, just too.

It’s the close of the year and I’m on the cusp of my 40th birthday. I ask myself one more time, am I happy? I still don’t know what that word means. But whatever I am, I can feel it.

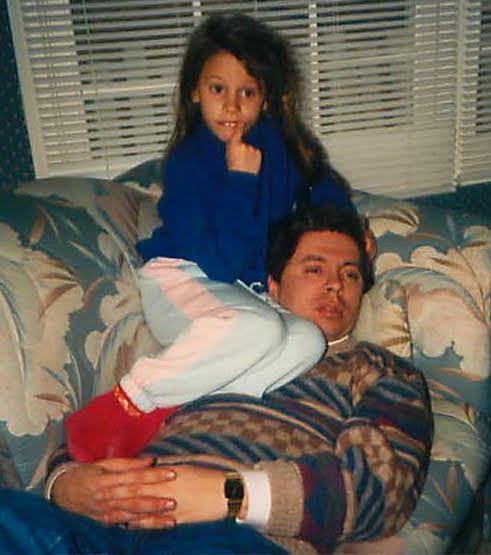

childhood photo of the author and their father contributed by Sarah (SC) Dillon

RITUALS is a nine-part miniseries edited by Vanessa Friedman. The writers who contributed to this miniseries will share all sorts of rituals: rituals for love, rituals for grief, rituals for forgiveness, rituals for inner peace. We’ll publish a few pieces each week through December 31. Please share your rituals in the comments, and let our contributors know which rituals in particular speak to you.

Thank you for this brave and beautiful piece.

I am sorry for you loss. Thank you for sharing this piece. As I grapple with the very fresh loss I am experiencing, I hope to able to share my story one day. It’s important that we acknowledge, learn, and grow from our, and others, experiences.

This is such an incredible piece, thank you.

This was so, so beautiful. I am really grateful you shared this.

Your writing about your grief touched me and I feel resonance with some of your experiences. I am so sorry you lost your father. I wish you time to grieve, rest and heal.

“…just 𝘴𝘰, just 𝘵𝘰𝘰.” Yes. Thank you.