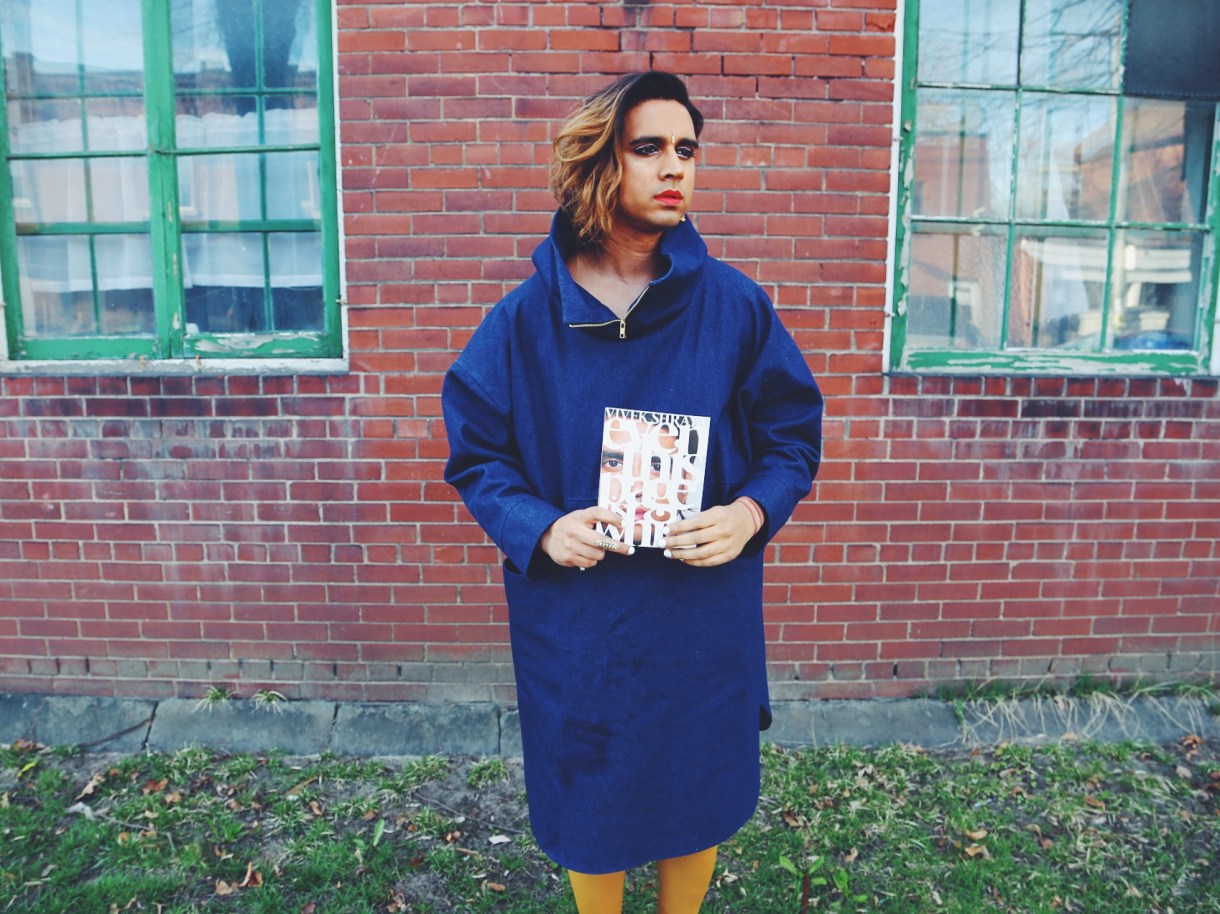

From “even this page is white” by Vivek Shraya

My friend Karen and I have a running (not so funny) joke: “No race on Facebook.” We have noticed that when either of us post status updates or links that speak about racism, they often get very little traction — a handful of likes, no comments. Curiously, when a white person shares the exact same link, I have also noticed that this often stimulates a discussion, wherein the white person is heralded for their post, and other white commenters share their allyship efforts.

Consequently, despite writing even this page is white, my first book of poetry, with the hope that it would stimulate more dialogue (particularly interracially) about racism, I also felt deeply pessimistic about the impact the book might have.

Who was this book intended for? Do people of colour need to read another book that discusses racism? Isn’t our lived experience enough? Is a white audience the default audience for any book about racism? And if so, wouldn’t this book be ignored—like countless other books and articles about racism by people of colour? Might it be more effective to use a white pen name, especially given that white men have no problem using names of people of colour for their supposed advantage?

Wrestling with these sentiments inspired the idea of including a poem-style conversation with white friends in the book. These are all people I greatly admire and whom I have been able to have vital dialogues over the years about racism—not only its impact on me, but also on the various industries and communities we belong to. While I worried that this inclusion might be read as a centering of white voices, from my perspective it was more about putting white people in the hot seat. Why is that people of colour have to bear the brunt of speaking out about racism while white people enjoy the privilege of remaining silent? What happens when the tables are turned? Of course, strategically, I also knew that white readers would likely be more inclined to hear what other white people have to say than what I had to say. But most importantly, my hope was that modelling conversation around racism and white privilege, topics that we tend to avoid delving into with each other, would inspire readers to continue these kinds of conversations with each other.

When did you realize being white gave you privilege(s)? What was that experience like?

Sara Quin: My awareness of racism and my whiteness started in junior high school. Our behaviour as kids—the way we talked, dressed, fought, expressed ourselves—was scrutinized on an entirely different scale depending on the race of the student. I was experiencing white privilege first-hand and knew then that it was unfair.

Amber Dawn: When I was in fourth grade my friend Thi and I were spending another lunch break in our teacher’s office. Both Thi and I had served lunch break detention before, had been sent to the principal’s office, and were regularly called “bad,” “stupid” and “lazy” by teachers. We were both poor. Both of us were surviving violence at home. During this particular detention, Thi tried to flee the office. The teacher grabbed her by the arm and physically dragged her back to her chair. I remember thinking that the teacher would never touch me like that. It took me many years to figure out that it was my whiteness that protected me.

Dannielle Owens-Reid: Once I started getting involved in queer spaces and met queer people of colour who had such drastically different experiences from mine, I was like, “Whoa, whoa, whoa,” and started to examine my understanding. I remember my friend Andre telling me about the challenges of being gay in a black family. As time went on, I would think about his story all the time, and then I met you and you had all of this knowledge that you explained in such a cool and easy-to-understand way. I had never really heard the word “privilege” but once you were explaining it so clearly, I was able to look back on my life experiences and see that you were right and it was legit. And I was so happy to have a word to define it. I’ve always felt a little lost in talking about racism until I met you because I didn’t have the ability to say, “It’s going to be harder for someone with immigrant parents, doesn’t mean they can’t have the good life, it just means they’ll have more obstacles, because people look at their parents, hear an accent and assume a bunch of shit.”

In instances where your white privilege has been highlighted, how do you manage any defensiveness?

AD: I listen. I let the person know I’ve heard them. I might ask the person if they need anything from me in the moment. I might offer an apology. I thank the person for taking the time to educate me. I let the person know that I will think more about what they said. I debrief with other white people. Sometimes, depending on the situation, I debrief and discuss with people of colour with their consent. I don’t expect any of this to feel comfortable.

Rae Spoon: The Toronto Star did a cover article on “they” as a singular pronoun and decided to put a photo of me on the front page. When the article came out, I found out that the paper had mainly interviewed white people who use the pronoun. Elisha Lim requesting “they” as a pronoun from Xtra and the boycott that happened until that paper started using it for people was a huge part of my own coming out as agender. Elisha brought up the exclusion of POC folks from the article with me. I had a moment of feeling defensive, and also I felt like I had really let them down. It felt like being wrong, and I wanted to do anything I could not to be wrong or to get out of the situation. I tried to remember what it’s like to be on the other side of that kind of space-taking, and I tried to keep it to a minimum. I wrote a statement on Tumblr about the exclusion and shared it in the same spaces I had shared the article.

How do you reconcile being white with the history of colonization by white people in North America?

AD: I doubt the small acts I currently do can be called reconciliation. In my working life, I read Aboriginal writing, both scholarly and literary. I include Aboriginal authors in my curriculum. When I have voting power as to how guest speaker funds are spent where I teach, I put forward the names of Aboriginal authors. When I receive author payments from work where I’ve written about sex work, I designate a modest percentage of that payment to the Missing and Murdered Memorial March Committee in Vancouver.

RS: The final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission defines reconciliation as an ongoing process of establishing and maintaining respectful relationships. Reading that really impacted me because of my own history with being the victim of abuse. It raised my awareness of the fact that I am approaching relationships with Indigenous people in Canada from the side of the abusers and the people who benefit from that cultural genocide. It means that I don’t get to decide how reconciliation happens and I am responsible for being informed and supporting self-determination for Indigenous people as well as calls to action.

DOR: I think about this a lot. I don’t think privilege makes any one human a bad person. I think ignoring your privilege, defending your privilege, or refusing to understand where that privilege comes from is the problem. I have privilege because the world is fucked up. I hate the history of North America and I hate the way it’s taught. I love when Columbus Day comes around and the Internet is flooded with “fuck that guy.” I think one of the best things we can do is recognize the true history and say, “No thank you, you guys did that and we are not okay with it.” Sharing the true history, the real stories, the actual events, that is so important.

One of the things that I’ve really struggled with, especially in the past year, is that in my social media feeds brown and black people are often posting links or commentary about racism or racial violence in the news but there is a kind of white silence. I have wondered why white people aren’t engaging. Why aren’t white people angry about racism?

AD: I think many white people are angry about racism, but white people are both consciously and unconsciously attached to power. White people are taught that our experiences are authoritative and right. When we learn to be allies, we must wake up to the fact that we are actually so fucking ignorant. We’re undereducated when it comes to just about anything outside of the white gaze, and we’re grossly under-practiced in talking about racism.

DOR: I think it stems from people feeling like if they say something, they are admitting to being racist. Or they are afraid someone will ask them about it, and they don’t know how to defend their point of view. People are afraid because if I were to say “Black Lives Matter” and someone were to say “Fuck you, all lives matter” and in my mind I’m like, “Oh yeah, I guess that’s true, all lives matter.” So now I’m in a place where I have no idea what to say to this person, because they are right, all lives do matter, but there is a clear imbalance and I don’t know how to say that, so I end up too scared to do or say anything at all.

Admittedly, I do feel resentful when white people do or say nothing at all, because of this fear you are talking about. So much of my own learning this year has been recognizing anti-Black racism specifically, how different this is from my own experience as a person of colour, and my own privilege in this respect. It has been challenging and even uncomfortable at times to know how to show solidarity. But I constantly have to remind myself that being an ally is ultimately learning to be comfortable with being uncomfortable. That it’s more important that I use my voice and privilege, and probably mess up along the way, than saying or doing nothing.

This has also been the year when I have been saying to white friends, it’s not enough to not be racist, I need you to step up. What are examples of your allyship towards people of colour?

SQ: I’ve always felt that one of the most crucial things a white person must do as an ally is to listen to the voices of people of colour—essential voices that are so often marginalized and silenced in mainstream society, it sometimes takes some extra effort to hear them. In my early twenties, I moved to Montreal and it was there that the world of social justice and politics really opened up to me. So many of the writers and thinkers I admired then and now are people of colour. I was compelled to learn from diverse voices and not just accept the perspectives of mass media. bell hooks and Angela Davis led me to writers like James Baldwin and Alice Walker. A dozen years later it feels even easier to find and be inspired by (new-to-me) writers like Hilton Als or Ta-Nehisi Coates. And that’s just writers. There is so much happening right now in music and art and on the front lines of the movement for racial justice that is being expertly and fiercely documented by people of colour. The idea of “listening” also involves being aware of what we’re consuming at all times. If my tastes become too homogenous—in music, art, or literature—I actively go out and look for other stuff, to make sure that I’m hearing those diverse voices. Learning from outside of a dominant white culture has truly enriched my life. And hopefully it has made me a better ally too.

DOR: I think sharing stories, articles, essays, videos from the point of view of people of colour is such a strong and easy way to contribute to a positive dialogue. I try to always be sharing a good solid tweet, video, write-up, from a person of colour because I think it’s important that those creators have the opportunity to create even more. I could retweet a white guy who says, “Racism ruins lives” or I could retweet a Muslim guy who is saying, “Racism is ruining my life.” That story is more powerful, real, true, and the perspective is what matters. I think (as with all movements) you need people from all sides standing up with/for you, but it’s important that the movement originates within that community.

RS: The only way to support folks when you have more privilege is to give power away (which means space, money/resources and time). I run a record label and put on a lot of the shows. When I’m looking at who I should play with or support artistically, I try to give space, resources and time to gender minorities, queer folks, and/or people of colour.

AD: It’s a bit of an abstract example, however I continually remind myself that getting involved is not about becoming a “good white person.” People of colour are in no way obliged to see or acknowledge any of my humble learning moments or acts of allyship. It’s not about “saving white face” to evade the reality of my own part in perpetuating racism. Allyship is gradual, delicate, challenging and life-long work. The work alone (not the outcomes or accomplishments) has to be and is reason enough.

I agree. The “good white person” is a myth, one that people of colour can’t afford to believe in. Especially when we are seldom shown the same kind of generosity applied in regards to our intentions—I am never perceived as a “good brown person” in conversations about racism. If anything, it’s usually the opposite. What is most important and needed is a person who listens and takes action.

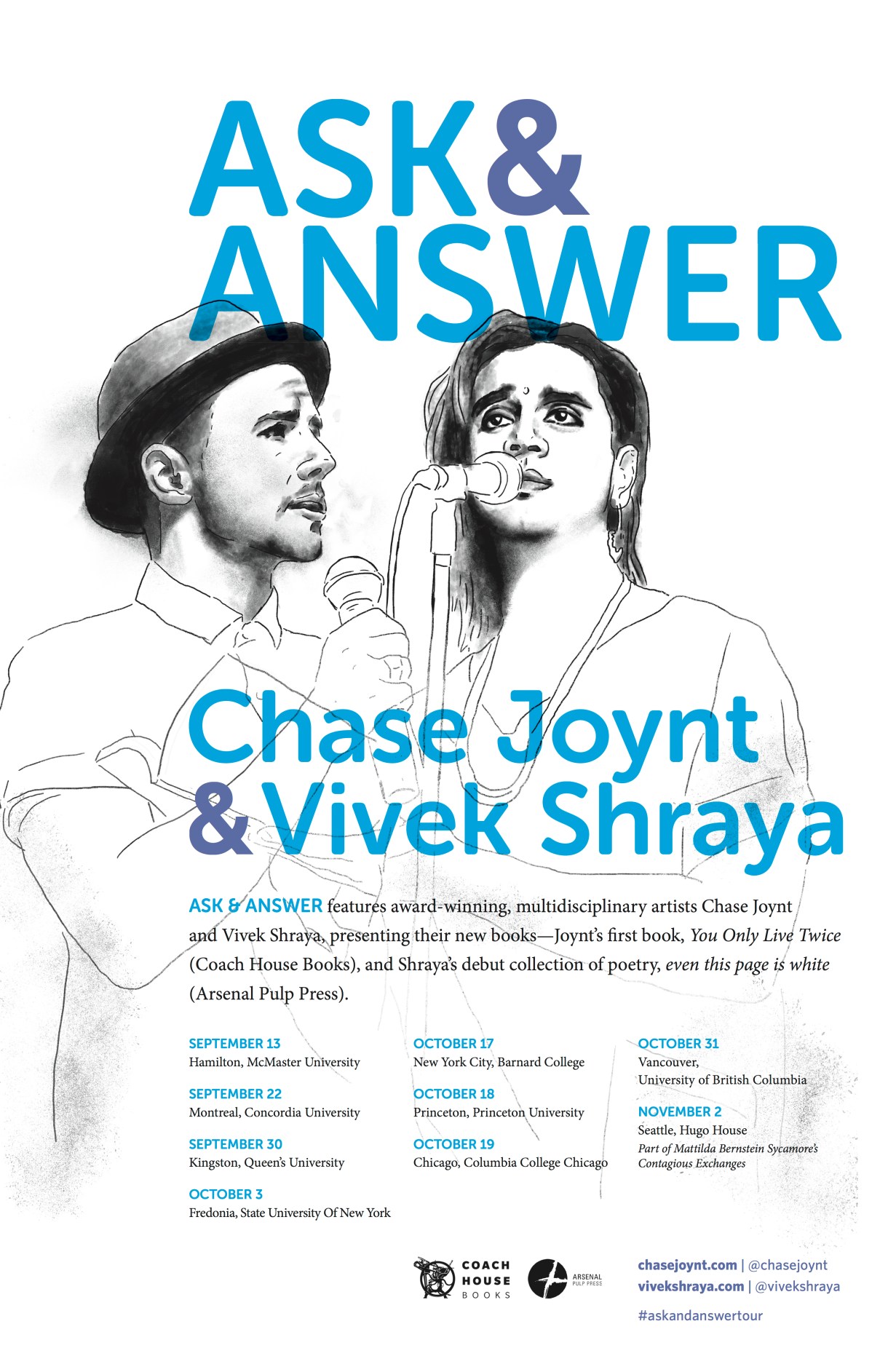

Vivek Shraya is currently on a book tour. The tour is called “Ask & Answer” and Shraya is joined on the tour by fellow trans writer Chase Joynt. Here are the US dates:

October 17 – New York, NY

October 18 – Princeton, NJ

October 19 – Chicago, IL

November 2 – Seattle, WA

Get more info at vivekshraya.com.

“But I constantly have to remind myself that being an ally is ultimately learning to be comfortable with being uncomfortable. That it’s more important that I use my voice and privilege, and probably mess up along the way, than saying or doing nothing.”

Thank you. This was a powerful piece.

This helps to force me to continuously put my own privilege in perspective and ask the same questions posited here. Thank you for this.

Thank you. Thank you for this.

Thank you for this.

I learned a lot from this, thank you

This was great, thank you.

This is excellent!

Very interesting

Thank you for this Vivek.

I really appreciate this discussion. I find it’s very easy as a white person to get caught up in the fantasy of being a “good person”. It’s so important to be aware of our motives.

I especially liked your comment about trying, even if you mess up.

So often I’ll second-guess speaking up because i’m afraid of saying the wrong thing, but really, that’s a selfish response. If I’m really open and acting not from my ego, then even if I mess up, I can learn and hopefully become a better ally.

I do notice that here in Vancouver, Canada, white people are extremely defensive if you talk about racism, and there seems to be a collective white fantasy of it being not racist here. I can’t believe how often I hear this! I think maybe my new comment will be that white people talking about racism is like a guy talking about misogyny. We can try and do our best, but we cannot pretend to begin to know, so we should damn well listen.

Thanks again – I hope we’ll see more from you on AS!

So good. Thank you. What an important conversation. I am also a white person who feels uncomfortable talking about racism and trying to figure how best to be an ally – I like the idea that allyship is learning be comfortable being uncomfortable. And Snaelle, I like your suggestion that “white people talking about racism is like men talking about misogyny”.

Thank you again!

huh!

Thank you very much for this, I found it really interesting and helpful. I think one of the most powerful lessons I learnt when I first began reading alternative media that featured people of colour and then intentionally consuming media created by people of colour, was the importance of giving space and amplifying voices of colour above white voices on issues of race.

Reading this though has made me realise, that under the guise of ‘giving space’, I have been using this as an excuse for not being as vocal an ally as I should be. This has been a really good reminder to work harder to find the balance between not taking up space that isn’t (or shouldn’t be) mine, but also not to leave all the work to people of colour.

Thank you for your perspective, the ideas, and the important reminder that I need to be doing more

Thank you for this article – incredibly important things to think about.

There’s lots of thought-provoking stuff in here, so thanks so much! It reminds me of how important it is to make sure I’m doing my best to be an ally, especially in my library work!

Thank you Vivek! I love your work, can’t wait to see you with Ivan coyote in Victoria!!!

Oh, my. It is only the simple minded who see the world in black and white. What are “white people?” Is it George Zimmerman, who shot Trayvon Martin? (Zimmerman is actually Latino). Is it Italian Americans, whose immigrant ancestors were considered a seperate, inferior race in the late 19th and early 20th centuries…the group considered by social Darwinists, like Margaret Sanger (the founder of Planned Parenthood), to be a plague on American Society? Is it Asian-Americans who are often viewed as “honorary whites” by other minorities because they rise up and out of the urban immigrant ghettos due to their strong work ethic (rather than becoming reliant on the welfare plantation)?

Really. Have you studied history? Ever?

Yes, the construction of whiteness is something to be considered in thinking about race and its connections to colourism, power, exclusion, and colonialism. At the same time, the actual complexity of whiteness does not take away from the reality and consequences of a homogenous white culture perpetuated by North American society.

Also, I hardly see how Vivek Shraya views the world in a black and white binary when she identifies as neither black nor white. She explicitly states that she is aware of the differences between anti-black racism and the racism that she has faced as a brown person.

LOVE LOVE: “So much of my own learning this year has been recognizing anti-Black racism specifically, how different this is from my own experience as a person of colour, and my own privilege in this respect.” I FEEL THIS SO HARD! Thank you for putting words to this.

this right here is the #1 reason I love Autostraddle, and will make donation tomorrow when my paycheck is deposited. :-)

Also for white folks trying to figure out how to show up, check out SURJ (showingupforracialjustice.org) – there are chapters all over and rooted in good values.

100% agree with the SURJ recommendation!! Really great org!