I was recently asked by a friend to share a list of speculative fiction films or books that were written by Armenians or told Armenian stories. I wrote back with a bunch of laughing emojis and said, “Yeah! Our work! Please let me know if you find anything else lol.” Seriously though, let me know.

When I think of what my family and ancestors have endured, I sometimes fear those stories aren’t being told for lack of an ability to imagine ourselves into the future. Armenians pride themselves on being part of a prolific legacy of artists, poets, philosophers, scientists, writers, and inventors. Yet (to my knowledge) very few Armenian creative minds have dared to dream into future or alternative worlds that center their stories, identities, and experiences.

Our ability to conceive of ourselves surviving and thriving into the future is a crucial part of manifesting it as a lived reality. The stories we see/read/experience on the page/stage/screen directly impact our capacity to imagine into said futures. It’s like a feedback loop, because as the stories we are exposed to impact our imagination, our imagination in turn churns out the stories end up telling ourselves. Then there’s the question of who is telling the story — especially when we’re talking about the stories that are being told on screen, we should also be looking at who is being chosen as cast and crew to bring these stories to life.

Let’s look at science fiction and fantasy, for starters. Both those genres don’t have fantastic track records when it comes to telling stories that center, well, anyone other than white men. In fact, most of the seminal writers and filmmakers of science fiction and fantasy are white men. Historically oppressed folks and communities show up (or just don’t exist) in painful ways, and their representation in science fiction and fantasy has been long-critiqued for perpetuating harmful and unproductive stereotypes and tropes.

It’s hard enough to think of mainstream film and television that centers queer and gender-variant folks, folks with disabilities, Indigenous, brown and black people of colour — let alone examples that include stories or characters from South West Asia, North Africa (SWANA), where my ancestors are from. At best, SWANA folks are featured momentarily (and usually in the background) as part of news coverage during apocalyptic moments: picture extraterrestrial spaceships looming over the Pyramids of Giza, or ethnically ambiguous brown men in uniform receiving news from the US president that everything is under control thanks to some white guy in a space-suit who is about to blow some shit up.

That said… the tides have been changing (for a while now). My heart is beaming as I reflect on the profound shift I have witnessed over the last few years — of the rise of popular creative works that dare to venture beyond the white-astronaut-will-save-us-all fallacy (seriously Matt Damon, we got this). More pointedly, works that tell stories of dystopian, utopian or alternate futures and worlds in which queers and people of color (their communities, their histories, their movements) are surviving and thriving on their own terms, by drawing from their own ancestral and cultural lineages, front and center.

So, when I saw the call for submissions for In Another World, I decided to pitch an overview of my favorite current or upcoming creative works by queers of color, alongside Ensouled (my latest project). I had the honor of chatting with Levon Kafafian, Autumn Brown, Jess X Snow, and Junauda Petrus. Their work is brilliant and draws on diasporic futurisms, speculative and visionary fiction, and/or the radical imaginaries of queer of color. The general framework I used to introduce my own project as well as my discussions with others looked at how fiction has inspired our work, how we conceive of our work as visionary fiction, how we are informed by our respective ancestral and cultural lineages, and who we are making this work for.

![]()

SHOUTOUTS & INCITING REALITIES

Before moving any further, it feels important to credit those who provoked and aroused this piece, and so much of my current work. My own understanding and hope for QPOC imaginaries is most recently informed by adrienne maree brown’s writing on radical imagination in Pleasure Activism. brown describes radical imagination as “a tool for decolonization, for reclaiming our right to shape our lived reality.” Now, if we’re talking about shaping our lived realities, we are also talking about visionary fiction work. The co-editors of Octavia’s Brood, brown and Walidah Imarisha, prefer the term visionary fiction over radical science fiction “because it pulls from real life experience, inequalities and movement building to create innovative ways of understanding the world around us, paint visions of new worlds that could be, and teach us new ways of interacting with one another”. I remember reading Octavia’s Brood around the time that I started working on World of Q (the storyworld in which Ensouled lives) with my creative partner lee williams boudakian. Knowing that there were other QPOCs out there dreaming into new and alternative worlds by drawing from their own lineages was a beacon of hope and encouragement to push forward on our work.

Beacons of all kinds are needed to do this work. lee is queer, trans, and mixed race. I’m queer, non-binary and Armenian. Both our families came to Canada by way of Lebanon and Syria through forced migration, and before that our ancestors were survivors of the Armenian Genocide in Ottoman Turkey at the turn of the 20th century. Now we’re here, living as uninvited guests on land that has been painfully colonized through the genocide of Indigenous peoples, while finding ways to live queerly on the fringes of our own cultural community. Now we’re here, trying to imagine ourselves into the future, together and on the shoulders of all those who came before us. I’m not just talking about our ancestors, I’m also talking about queer, POC, and indigenous science fiction artists and writers (especially Octavia Butler, perhaps the brightest beacon of all) who carved the way for the rest of us.

On that note, I’d like to introduce World of Q and Ensouled.

![]()

WORLD OF Q & ENSOULED

World of Q is an interdisciplinary, constantly-evolving creative project featuring distinct iterations that revolve around a central storyworld. In this world, hackers, healers, and cultural workers have formed an underground movement to resist totalitarian erasure of cultural and ancestral practices and memory. World of Q visions into the futures of those who have survived and thrived since time immemorial, by drawing from the stories, relationships, skills, and ontologies of their communities and peoples. The most recent work we created as part of World of Q is a short film called Transmission, which was a collaboration between Kalik Arts (an arts company that lee and I founded) and co-directors Emily Mkrtichian and Anahid Yahjian.

Kamee in Transmission (2019) by lee williams boudakian, Kamee Abrahamian, Emily Mkrtichian & Anahid Yahjian

My current project, Ensouled, grew out of this co-created storyworld. It’s an intergenerational narrative that weaves magical realism and speculative fiction with histories of resistance movements and elements of SWANA culture. The characters and landscapes draws from my experiences as a queer, diasporic mother. The story follows a solitary hacker and botanist (Badaskhan) who translates frequencies from the plant-life growing in their greenhouse and lab. The story is set in a near future where a totalitarian regime has nearly wiped out an entire generation of resistors, elders, and keepers-of-ancestral knowledge. As pressure mounts to join a growing underground resistance movement carried forward from the last generation’s efforts, Badaskhan buries further into their work as they become obsessed with recording and decoding unusual frequencies from a newly sprouted plant. The frequencies slowly reveal themselves to be secret correspondences between Badaskhan’s ancestors, a group of women resistors and practitioners of magic who survive on their own terms in Ottoman Turkey at the turn of the 20th century. Badaskhan, who has long denied their family history and Armenian ancestry, is now forced to contend with a resurfacing of painful childhood memories.

For me, Ensouled is an interdisciplinary and iterative in both form and intention. In terms of form, I’m currently developing it as an illustrated storybook (drawn by Lorik Khodaverdian), which is on track to completion by Spring 2020. In August 2020, I’ll shoot a series of short videos that pull scenes from the book, and build towards creating an immersive installation as well. My long-term intention is to make a feature film, and possibly a digital storytelling platform. In terms of intention, at the forefront of it all, I’m trying to push back against mainstream damage-centered narratives of my people whilst imagining the magic that I know my ancestors practiced but never wrote about. Throughout my childhood and until now, I am inundated with tragic stories about the Armenian Genocide and from the SWANA region in general. I will be the first to acknowledge that a good old staring contest with my own experienced and inherited trauma is the first step towards healing. That said, my concern (always) is with the who’s, why’s, and the how’s of the stories we’re telling. The stories of women from my own lineage are often times brutal and graphically-violent. I’m also (always) cautious of the nationalist rhetoric that is heavily present in my ancestral stories. Without denying that these were brutal times, I’m allowing myself to be curious about how the women and queers that came before me survived and thrived, and how they supported each other across borders and ethnicity. At the same time, I’m giving myself permission to imagine what it could look like to combine all this with an element of magic, through and alongside all the heteropatriarchal religious rhetoric of our communities and histories.

So… I think it goes without saying that I was over the moon (the whole solar system, really) when I found out that World of Q wasn’t the only project that manifested a queer, SWANA speculative fiction storyworld. Especially one that was telling multi-iterational, interdisciplinary stories that drew from our cultural lineage while also bending time and place.

![]()

PORTAL FIRE

Levon Kafafian came to a World of Q workshop that we facilitated at the Detroit Allied Media Conference in 2016, and I’ve been following their work since. Kafafian is a Detroit-based interdisciplinary artist who blends their weaving craft into a visual, performative and social practice. Their practice is primarily interested in queering ancestral reclamation and speculative discourse and storytelling. Kafafian is also the co-creative director of Fringe Society, “an artist collective that creates hybrid, experimental works toward a more just and equitable future.”

Photo by Christian Najjar

Kafafian’s latest project, Portal Fire, is a tale of blurred boundaries, false borders, and questions of cross-cultural coexistence. It takes form as an immersive narrative experience supplementing a graphic novel with handcrafted objects, audio, film and performance. Hospitality, craft, music, divination and storytelling are made tangible as they are essential components in SWANA cultural heritage and therefore play a prominent role in this narrative. The first iteration of the project is called “Once There Was and There Was Not” (fun SWANA fact: the title of this project is a reference to how classic Armenian stories usually begin!), which premiered during Kafafian’s residency at the Arab American National Museum this year. They have a couple upcoming shows/installations that further build on the Portal Fire project and storyworld, and the graphic novel is currently in development.

Portal Fire was born out of Kafafian’s two simultaneous obsessions and deep loves: the realms of anthropological, archaeological, scientific and linguistic knowledges, and the world of young adult graphic novels, science fiction and fantasy, and anime. Funny enough, I was sitting between the science fiction and graphic novel sections of the library when I called Kafafian. During our conversation, Kafafian told me about how all the data they consume tends to organically synthesize in their work, and how so much of what they produce as a queer-SWANA storyteller requires a deep, embodied excavation of sorts. “When I think of our ancestry, I think of how we have had to reverse-engineer or reverse-figure-out our current practices as descendants,” Kafafian explained. This really resonated with me, of course. They went on, “I was initially inspired by the fact that I could not find graphic novels that were in the sci-fi or fantasy genre produced outside the orientalist lens and about SWANA stories. Lots of SWANA-produced magical realism and autobiographies and personal/collective histories, but the future-facing stuff was missing.”

“Once There Was and There Was Not” – Courtesy of Arab American National Museum

I wasn’t surprised to hear the response to my question of who they were making this work for. “For myself!” they laughed. “And for young queer people in and from the SWANA region… I just want kids to see that they aren’t alone and that they don’t have to be one particular way.” That’s why the main character of Portal Fire’s first chapter is non-binary. They intentionally wrote the character that way, so audiences wouldn’t be able to pin the tail on the gender-donkey. Kafafian also referred to how this project, and their work in general, is one of many ways that they are actively undoing misogyny and hyper-masochism in the Armenian community. “There are so many expectations… your family, your community, your gender. I’m doing all I can to show readers that other things are possible… and valuable.”

This idea of QPOCs creating the work that they wish was available to them when they were young makes a lot of sense to me, and it is something that came up in all my conversations with the other artist and writers I spoke to.

![]()

THE STARS AND THE BLACKNESS BETWEEN THEM

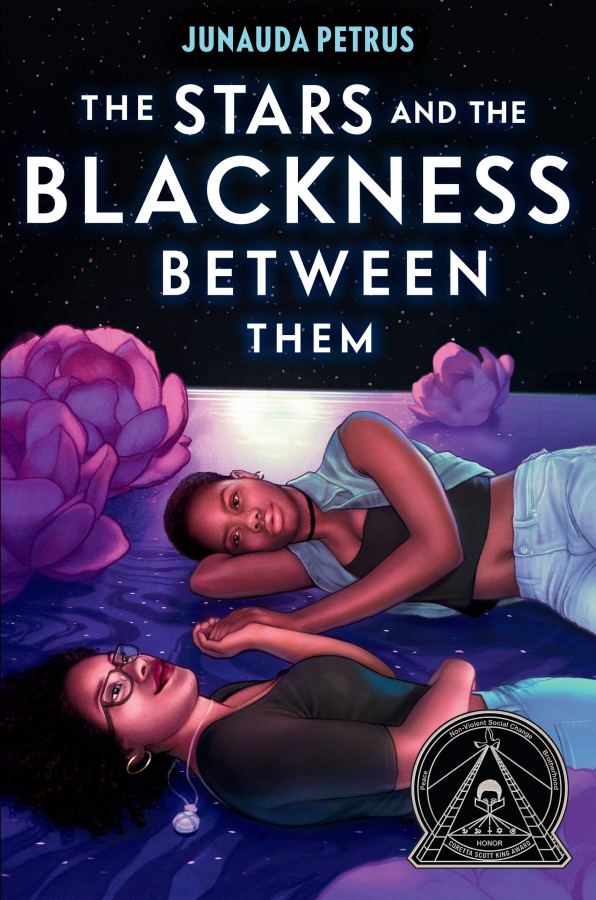

Junauda Petrus is a black, queer creative activist, writer, playwright, and multi-dimensional performance artist who was raised in the Midwest on Dakota land. She recently wrote a young-adult fiction book called The Stars and the Blackness Between Them. It’s described as a “bold and lyrical debut is the story of two black girls from very different backgrounds finding love and happiness in a world that seems determined to deny them both.” Through her writing of young adult fiction, Junauda is committed to affirming and healing the importance of pleasure and sweetness for BIPOC and LGTQIA+ youth.

My conversation with Junauda was weaved with a profound sense of her own growth and blossoming as a diasporic futurist and pleasure activist. When I asked how her ancestry is present in her work, she said “A lot of my writing came from having to re-imagine my histories, and also reclaim spaces of queerness in my legacy as a carribean and person of African descent.” Junauda also continuously honored those who made her work possible as well as the descendants for whom she is largely doing this work for. “I read Zora Neale Hurston, Alice Walker, Rosa Guy in high school and they were so powerful for me to stumble upon… I give thanks to my lineage of writers who did this before me who gave me permission to live and not die.”

Junauda’s history of working with youth came up a few times as well. “How can I give myself permission to write this work, to make others feel that who they are is okay…” It became so clear to me how so much of her work is interested in healing traumatic legacies around the body and sensuality, and giving people “the opportunity to love themselves and to love life… to feel entitled to pleasure, to be in relationships with themselves and each other.” According to Junauda, this is exactly why she turned to speculative fiction and black diasporic futurism, because it allowed her to lean into what is possible. She also told me how salient it was for her to learn about the multidimensionality of blackness, especially as a queer person. “Oppressed bodies are often forced to conform to this greater mainstream construct, so many ways people need to be given permission to be curious about themselves and be visionary about the things that are tethering us.”

One of the main questions that guided Junauda in writing The Stars and the Blackness Between Them was how to write a book that was needed, one that envisioned and imagined into possible worlds and futures that told a queer, black story in way that honored all its complexities. Or, in Junauda’s words, “what is it like to have two black girls falling in love in this limitless cosmic diasporic way, that is also humourous and sexual and sensual and consensual?… All of these things I had to find out in complicated and sometimes painful ways.” As part of this process, Junauda learned to push back against the idea that “whiteness is deemed as the origin story” and then to look “more deeply at my own legacy, before my parents and ancestors, beyond what was forced onto me as my story.”

Cover of ‘The Stars and the Blackness Between Them’

Towards the end of our talk, Junauda generously reminded me that we all need to be understanding each other’s stories, especially because mainstream media is so inundated with white-cis-het culture. “It becomes difficult to understand and access other people’s experiences, you never know who it will touch.” Junauda’s final thoughts to me called on a recent shift in people’s perceptions of how important it is that we speak through our own experience and lineages (she referred to the #ownvoices movement here). She went on, “…at the same time, these stories aren’t just for people in that particular demographic or culture. Lots of different kinds of people connect to my work.” This brought me back to the feedback loop I mentioned earlier — QPOC visionary fiction work isn’t just by us and for us. It is also contributing to a shift in the overall dominant ideologies of what should be considered mainstream in the first place.

![]()

SMALL AND BRIGHT

At the mention of origin stories and ideologies, I can’t help but think of Autumn Brown’s novel-in-progress, Small and Bright. Autumn is a queer, mixed-race mother, organizer, theologian, artist, and facilitator. I have been listening to her and her sister on their How to Survive the End of the World podcast since the beginning of its inception. I kindly gave the fan-girl inside me something cute and fluffy to play with as a distraction so I could focus on my conversation with Autumn. We talked a lot about her book, and we also got into how visionary fiction and mothering-as-practice sits at the center of her political and movement work.

Science fiction has always been Autumn’s preferred genre to read, long before she started identifying as a science/visionary fiction writer. “Octavia Butler and other women, femme, and queer writers — they’re writing the kinds of narratives that I want to read.” She continued, “…particularly narratives that feature the voices and stories and bodies of people who aren’t represented in mainstream science fiction and fantasy. Authors who are also drawing on and writing in their lineage.” Autumn’s book is doing precisely that, not only in the stories she is choosing to tell, but also in how she’s following in a long line of writers who just get the damn thing done (meaning, they take it upon themselves to write themselves into the works they felt absent from). From my own point of view as a parent, I see this act of ‘getting things done’ as an act of care — akin to the work of parenting, of caring for the future well-being of an-other, of picking up the slack, of taking on the labour that is often so invisible. In this case and much like the other creators and writers in this piece, Autumn is doing the work of making-visible and making-possible.

I had previously read Small and Bright as part of the Octavia’s Brood anthology, which happens to be the first chapter of her current novel. It tells the story of a community that lives underground due to an apocalyptic happening. They also believe themselves to have moved beyond ideology as a construct. The narrative follows a character named Orion is being forced onto the surface of the planet (it’s called being surfaced) as part of being punished for a crime she committed. She is separated from her infant son as a result. Just before she leaves, Orion’s parents tell her about a community that found a different way to survive on the surface, and that part of her survival depends on her connecting with this community.

“When I started working on it, I didn’t understand it to be a book about grief and loss.” Autumn was intending to write a book that explored origin stories and looked at how communities understood their origins in terms of what are considered to be legitimate stories to pass on. “When I lead visionary fiction writing workshops, I share with participants that we are in an imagination battle… the onus is upon us to be visionary as a part of our process of liberation.”

Autumn told me that this process is contingent upon aligning our imagination with our values. It became clear to me that visionary fiction was not only part of her writing process, but her political practice as well. “When I’m working with social movement organizations, I’m also trying to create a sense of shared responsibility to be as imaginative and visionary as possible… because right now we’re operating under political conditions that we absolutely have a lot of influence over.”

The inclusion of children and the role of parenting in society is also a major part of Autumn’s writing and visionary work. When I asked her who she’s writing her book for, she flipped the question on its head and said, “I’m trying to audience the work of parenting.” Beyond challenging herself to write narratives that reflect her own life, identity, and her beloved family and community, Autumn said her intention is to highlight the role of parents in society, and to influence her readers to really look at the centrality of parenting in how we reproduce the society that we want.

![]()

LITTLE SKY

Last up is none other than Jess X Snow, a queer immigrant asian-canadian artist, filmmaker, and poet who wrote and directed a short musical drama called Little Sky. The film follows a non-binary Chinese-American drag queen who returns to their home town to confront their estranged father about the childhood memories that continues to haunt them. It was executive produced by queer Korean filmmaker, Andrew Ahn, and it’ll be released in 2021.

Film Still from Little Sky

Jess has a formidable interdisciplinary creative body of work that includes film, large-scale murals, poetry and community art education. They describe themselves as “working to build a future where LGBTQ+ migrant people of color may see themselves heroic on the big screen and city walls & discover in their own bodies, a sanctuary for healing and collective liberation.” I was introduced to Jess through their work with Justseeds. My heart skipped a beat when I learned about their arts activism and trauma-informed healing practices, and how “they bring together diasporic communities of color and allies to create inter-generational stories spanning genres of speculative fiction, fantasy, and musical.” My heart nearly stopped entirely when I read the logline for their last film, Safe Among Stars, a story about a queer chinese-american woman who “struggles to tell her immigrant mother and partner the truth of what happened to her. As her trauma causes her to develop teleportation abilities, she must learn how to control her powers.”

Talking with Jess reminded me how much of ourselves we draw from when we do visionary fiction work. “Since I was a kid, I had a stutter and moved across borders and states multiple times, and to cope with the transitions, I would imagine worlds beyond this one, where I could find joy and sense of belonging.” As a survivor of domestic violence and intergenerational trauma, Jess always used poetry and art to create realities in which QTPOC main characters coming from broken families confront their trauma and ultimately find the belonging they so yearn for in themselves. This carried over into their work and films very pointedly. Jess described a scene from Little Sky, which takes place just after the main character, Sky (played by poet and drag performer Wo Chan) confronts their father about domestic violence. They are comforted through song by another non-binary, Asian friend, Miyo (played by actor/singer Kyoko Takenaka.) “This moment encapsulates the unspoken understanding and compassion that people in the queer community exchange to each other after witnessing difficult and traumatic events.” Jess admitted that although this scene was inspired by the idea of queering the parking lot scene from A Star is Born, their biggest influences for Little Sky were Spa Night (by Andrew Ahn), Moonlight (by Barry Jenkins), and Farewell My Concubine (by Chen Kaige). “I wanted to combine the grandiosity of a musical with strong visual elements, powerful non-binary characters, time travel between memory and the present, and emotionally-driven acting to make something that Asian American cinema has never seen before.” Little Sky was created with a diverse crew that had many queer and non-binary people of color on screen and in key crew positions.

Little Sky BTS with Jess X Snow and Sueann Leung

The costumes in Little Sky were designed and built with meticulous attention to detail by queer non-binary Asian American costume designer, Sueann Leung. Their concept for the final scene was to simultaneously pay homage to and to actively queer traditional Peking Opera and Kabuki costumes. The design is driven by the desire to reclaim access to our histories while creating a narrative future reflecting our Queer Asian American diasporic experience.

Jess’s work specifically asks what speculative fiction and fantasy looks like for Asians and diasporic Asians. “I think for a long time I didn’t feel proud about being Chinese,” Jess admitted. But since Jess has been building community across the asian diaspora, they’ve been drawing from their ancestry and looking more deeply at their own histories. “In western colonial thought, it’s all about conquering and discovering externally… whereas in Buddhist philosophies, driven my mediations, there is this anti-colonial idea that all you need is to look inside yourself, and accept what you find, and you will find all the answers. Decolonizing how western philosophy and capitalism has shaped my creative process, and letting in inspiration from ancient Chinese art and poetry has reshaped my approach to filmmaking.”

Film still from Little Sky

I asked Jess how this was reflected in Asian cinema, specifically with speculative fiction films. “Lots of anime films show these cold, dystopian futures. My hope for the future of Asian science fiction and fantasy is to show decolonized futures where people are learning how to love and reclaim their relationships to land and family. I also hope to see more indigenous people’s voices centered, and in leadership positions. I believe it’s the responsibility of all people across the asian diaspora the uplift the pacific islander and indigenous people across this Earth.” Jess also mentioned how important it was for QTPOC youth to see themselves on screen, and added that they’d like to see more queer elders represented in film as well. I thought this was an important point to make, because it is just as important for QTPOC’s to hear queer elder’s voices, and to imagine themselves into eldership as well.

![]()

Writing this piece has brought up all the feels for me. I jumped through a Portal Fire to float through The Stars and the Blackness Between Them, and though I was able to encounter only a select handful from the infinite, each one of them Small and Bright, in the end I completed this leg of an ongoing journey feeling assured that I am ultimately Safe Among Stars. The imagining and visioning of potential/inevitable/already-here worlds and futures is crucial and necessary, it is the work of making-possible. Immersing myself into the brilliant storyworlds that Levon, Junauda, Autumn and Jess have brought to life has helped me hone in on how my own creative work is also making-possible. Learning about who they are and why they do their work has reminded me of the magical potential and plurality of the many worlds I belong to and hold within my own self.

The work of visionary fiction is also as powerful as it is relational. We are always in relationship with the stories we are told, the stories we tell and who we tell them to. I wish I had more time to include other projects (because there are more). I encourage you to follow the folks I had the honor to include here, and above all to continue supporting artists and writers who are doing this kind of work.🔮

Edited by Rachel

This work sounds so beautiful and exciting, I’m salivating!

I cannot wait to read/view/explore this stories/films/works! As a queer half-Armenian-raised-white who has a hard time imagining a future where I get to bring my Armenian heritage with me and pass it on to future generations, I am cherishing this article.