Like many a suburban white girl looking to rebel, I celebrated my eighteenth birthday with a tattoo. Not as a middle finger to my parents—who both came along to watch—but a disruption of expectations. Tattoos belong on cooler people than me. (It bothers me, for example, that the grammar in that sentence was wrong, and that I have to leave it because “cooler people than I” is a bridge too far.) But I liked the idea of wearing something I love permanently. It felt bold and surprising, unfamiliar sensations for the risk averse. And if nothing else, I’d have proof that I once survived an experience not everyone can handle. I hadn’t realized that cerebral palsy means I do that every day.

I chose a treble clef on my right hip with the rationale of a lifelong choir kid: “I’ll always like music.” I’m happy to report that is still, as of this writing, true. But the landscape shifted between tattoos one and two. I experienced my first full-scale bodily betrayal, an out-of-nowhere spinal fusion surgery, and was riding out a ripple effect that would take years to settle. I could sense that my body would not be denied and that I should probably start getting to know it. That maybe it was time to explore its dark corners.

I wanted a design that spoke to disability without hitting it on the nose. I’m just not the kind of person who can pull off the International Symbol of Access (you know it from parking spaces), the wheelchair heart, or this little guy as body art. Not a chance. Maybe it’s that I’m not a wheelchair user, but those images don’t do it for me. They feel too generic and easy. They’d get the point across as tattoos, but say nothing about my actual experience in this body. I needed something more individual and complicated, like CP itself.

Jillian Weise’s The Amputee’s Guide To Sex is one of the few books I remember receiving for the first time. A college friend put it in my hands the summer before senior year because she could tell I needed it. I was so fragile then. The surgery still felt too real and like it might not stick. I’d been kicked out of my body and not yet moved back in. So I honed my mind while staying physically adrift. It was kind of like living in a museum—look, but don’t touch.

I think that’s why I found Weise kind of brutal at first. She was so honest; all the fear, pain, rage, and doubt I swallowed without acknowledgment, she just put right out there. She wasn’t hiding. She had no shame, or no shame about her shame. I’ve never been much for poetry, but hers punched me square in the stomach. It was everything I felt but wasn’t ready for.

I barely noticed “Erase,” the forty-second poem in Amputee’s Guide, when I devoured the book in one night. It’s easy to miss amidst the pieces about sex or a suicide from being “always in pain.” Those have the shock value to linger; they’re visceral and unapologetic, and I wasn’t prepared. I didn’t get “Erase” yet because I couldn’t. This is back when words like “despite cerebral palsy” still felt natural for me to think and say and hear. But when I cracked open Amputee’s Guide on the tattoo hunt, there it was:

It is not you who keeps me

in hiding while you walk

nude through the house.

This will not change,

in the thick of things we are.

If I am to explain, then

I must go back to the family

dinner when I am nine,

when I meet Otis for the first

time, an uncle who wants

to know about me, but not

how I’m doing in school.

He wants to see the body

up close, unfamiliar.

I am told to unbutton

so everyone can see where

they stuck ribs in and stitched.

Otis recommends Vitamin E

for erasing parts of the body

that bother other people.

The suggestion that you manicure your disability (like you’re plucking your eyebrows or fixing your hair), the hungry curiosity, the gut reaction to stay “in hiding” while everyone else “walks nude through the house”—I’ve felt all of that, deeply. Sometimes I do it to myself. That’s the ableism I know: benevolent, well-meaning, even familial. The kind that everyone understands is wrong almost never happens to me. No one yells at me on the street, I’m not being denied social services or lifesaving care, and walking means that I can access most spaces (if not always on the first try). Instead, I get pity dressed as compassion. I get “I forget you’re disabled!”, glares for not giving up my seat on the train, and congratulations on being “so close to normal” (yes, that’s an actual thing somebody said). Able-bodied strangers ask “what happened?” not as an accusation, but in a way that invites sympathy. As if I’m going to say “yeah, it sucks, doesn’t it?”. They expect common ground. I look and behave and sound and succeed so much like them that I get an honorary spot on the team. That’s what ableism looks like filtered through privilege: an invitation to distance. Vitamin E for erasing parts of the body that bother other people.

I am not the one who’s bothered. Inconvenienced? All the time. Exhausted? I need a nap pretty much every day. But having cerebral palsy, and the body it built, does not bother me the way people seem to think it should. It would be easier for them if I was ashamed or wished for “better.” But I’m not myself without this body, and you know what? I like myself. I’m not supposed to, and getting here was scary and took a long time but now that I am, I don’t plan on leaving. I don’t need the Vitamin E; they do. So I put it where they can see it and I can remind myself.

I figured that would be enough; when someone asked for my tattoo story, I could tell them about Jillian Weise and not erasing me and yes, for sure, it lets me do that. It sneaks up on people who don’t know they offered me a soapbox until I’m already on it. I love watching them realize what they’ve gotten into. But for as much as the design says on its own, it means even more as a part of my body that everyone can see.

Being looked at is tricky for a lot of disabled people. Because one of the first lessons anyone learns about us is “don’t stare.” It’s rude and invasive. And yes, sometimes the blatant gawkers just get you on the wrong day and hit you in that spot that makes you feel inferior. It’s draining (and sometimes even dangerous) to be out there when your body isn’t supposed to exist in public. So “don’t stare” is simpler for us too. But here’s the thing: if you don’t stare, you also get to keep ignoring. And ignoring us, I think, is the bigger disservice. It keeps us unknowable and absolves you of the work of seeing us. Not just the parts you like—the ones you find “inspirational” or that “teach you so much”—but the uncomfortable ones. The body up close, unfamiliar. And I love having art on my body that forces people to look at all that again. Makes a body they’d rather avoid into a visible one. Turns something that happens to me (because yes, I know you’re looking) into something I make happen.

The other big issue is choice. I made a choice about how I would look, and didn’t realize until I’d done it how unprecedented that was. Because disability is really good at eliminating choices. It dictates where you can (realistically) live, how much you can get done in a day, how people think about you, and what you look like. You don’t get to decide how it shows up. Doesn’t mean you have to hate it, but you do have to work with it. The tattoo gave me some of that visual autonomy that disability can so easily take away. And, most unexpectedly, it helped me recognize and redefine my body as queer.

I had been out for years by this time. I knew I was part of the “queer community.” But I’d always felt a certain aversion to the word. I prided myself on a pretty cut and dry sexuality; having come out relatively young (in high school), it kept me safe and and mitigated a lot of fear and uncertainty. Plus, disability already made my body strange and unwieldy. I didn’t have the energy for anything more complicated. So when queer started to happen, I kind of wrote it off, assuming that I must have already done the required homework. I preferred to ignore inconvenient ideas that challenged me any further. Pick and choose what I liked and leave the rest. Sound familiar?

Putting this art on my body, setting it apart even further from others, made me realize that disability is nothing if not queer. Think broadly: curious, odd, different, outside of our norms. Disability will do that to your body, orientation be damned. And that understanding gives mine the room to be everything it is. Top to bottom, excluding nothing, messy and fantastic and tenacious. Illustrating that fact on my skin, celebrating and being intentional about it, makes me feel like my body and I know each other now. Not because “I’ll always like this,” but the harder truth: “I’ll always be this.”

That this will not change, in the thick of things we are.

Carrie, I have enjoyed this series immensely, and this one is my absolute favorite so far. You are a brilliant writer and thinker. I feel so lucky that you’re sharing yourself and your work with us.

I won’t lie, reading this made me tear up. Thank you–that feedback means the world coming from someone whose work I’ve admired for so long. We’re all the luckiest to have you around, too.

Every time. Your work is consistently great, and remains my favourite column on this website.

Thank you for such high praise! Wow. I’ll do my best to keep up the standard! It’s been such an adventure writing these so I’m really glad you’re enjoying.

Thank you so much for sharing this. I got visible tattoos a few years ago as a reminder for myself when I am dealing with my clinical depression. When I was finally really dealing with the fact that this doesn’t go away, it is something I will always deal with (but I can and will because living is worth it). People of course always ask about them (a pair of lyrics in Japanese on my wrists), demanding to know why I would do such a thing to my body. When I translate you can tell by their reaction what ‘opinions’ they might have about depression.

I know it isn’t exactly the same situation as yours, but I definitely identify with the idea of choosing something for a body/mind that seems to have turned on you, that the world tells you to hide or cover up. This is so important.

“Choosing something for a body/mind that seems to have turned on you, that the world tells you to hide or cover up.”

So well-said! Thank you for distilling my many paragraphs into such a concise statement. I’m glad you enjoyed and, more importantly, that you’ve found ways to connect with your body and mind too.

An intriguing read to start the week!

This made me cry a little bit.

I was in an accident a little over two years ago, an accident that’s left me with chronic pain and any number of potential future health problems.

I decided to get a tattoo on the anniversary last year in part as a symbol of what I’ve overcome – I lost a fight to a dragon and survived, and now that dragon lingers on my back.

But it’s also a control thing. When I felt so robbed of choice about my body, about my appearance, as nurses bathed me and I wake up with new scars from surgeries, I needed to feel like I could make a permanent mark on my body that was mine. Disability limits my choices in so many ways, but in that year it limited every choice I made about my body and I needed to take that back.

Thank you for writing this.

And thank YOU for sharing that with me (and everyone else here). I know exactly what it feels like to wake up from surgeries with new scars, unfamiliar hands on you, and no idea what to do from here. Bodily autonomy is so crucial, especially when your body’s been through some things, and I’m so happy to hear you’ve been able to take some of yours back.

This is brilliant <3

Thank you for saying so!

I was about to write “I will be so mad if you don’t ever write a book!” but like hey, entitlement, so what I actually meant was, I would gladly read a book-length compilation of essays like this, it would be super rad.

Ha! Well, that’s the master plan, so no need to feel entitled. I’LL be so mad if I never write a book (or at least never try). Thank you for saying so!!

I was hoping you will be writing a book! You are truly an amazing writer.

I have a tattoo that references chronic illness. One of the other powers it gives me is the power to *not* talk about my health if I don’t want to. When someone asks, I decide whether to tell them it’s a reference to a poem or to go into what it means.

this is so good, i cried a bit too. thank you for writing these texts and for sharing your perspective and insight. i can’t wait to read more.

especially this part hit my core: “The surgery still felt too real and like it might not stick. I’d been kicked out of my body and not yet moved back in. So I honed my mind while staying physically adrift. It was kind of like living in a museum—look, but don’t touch.”

i had some surgery last year as well (for a bone tumor), and this is exactly what it felt like. in the end i got a tattoo that really helped me come to terms with my body again, partly also because of the choice and intentionality, like emma said above.

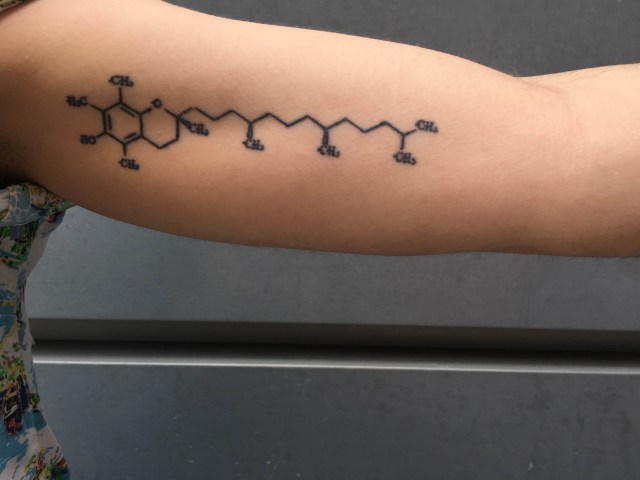

i’ll try to embed a picture of this (hopefully it’ll work, i haven’t done this before):

I love it!! Thank you so much for sharing.

This is fucking beautiful.

Yes- it is Fucking beautiful.

Fully agree.

Shucks. Thank you both!!

I have pretty bad chronic pain, among other things, as a remnant from a spinal cord tumor I had at 14. This really spoke to me. I wish I had more to say but I’m feeling a lot of things and I just wanted to thank you for writing this, with all my heart.

Thank you for reading, with all MY heart! And, of course, for sharing that part of yourself with us here, in whatever small way.

Every one of your columns hits so close to home – both so like my own experiences and yet completely different. Beautiful and painful all at once, just like getting a tattoo. Mine is less directly symbollic of my disability, but was still such a huge moment in reclaiming and inhabiting my body. I can’t wait for your next column, thank you for writing!

Thank you for reading! And “beautiful and painful all at once” is a pretty spot on description of life with a disability, so thank you for that too. Well said.

This is an interesting way of dealing with disability – tattoo art would not have occurred to me as a reminder and morale builder. The molecule looks good! There is a book out there about scientists/mathematicians’ tattoos.

In each article you are unfurling a new part of yourself. Your writing is a carefully crafted invitation to see you up close, and as you are. Piece by piece you are revealing yourself to be complex, intentional, crystalline, beautiful, vigorous, and so thoughtful. A Virgo in bloom. Your writing is brilliant, elegant, and clear. Exactly like a Hildegard song. I knew something about it was brightly familiar.

You know the way straight to my heart.

(Hint: it’s via Hildegard.) <3

There aren’t words for how much I appreciate this article.

I have a lot of trouble being in my body, and it’s hard for me to even imagine what having a healthy relationship with my body would feel like. But the way you write about your body helps me start to imagine some different ways I might relate to mine.

“I’m not myself without this body” – I love this.

Thank you! I woke up from a dream that made me wish I was a different version of myself – the one who could look like anything or anyone with a change of outfits and a couple easy choices about how to move;, the old pre-disabled me. So this rings on my frequency…

Wow another great piece. This has been a really eye-opening series. Thank you.

Thank you so much for this beautiful and well-written piece.

I was abused as a child for seven years and have been dealing with the resultant PTSD and depression and anxiety for almost a decade now (and I’m only 20), so I understand at least parts of what you’re saying.

A tattoo is something that’s been on my mind too. For me, it would be a line from one of my favorite books (A Tree Grows in Brooklyn) in some sort of readable but handwritten script down my left forearm. In the context of the book, the line describes how the women of a particular family (the Nolans) suffer and can appear frail, but ultimately “they were made out of thin invisible steel.” The image of a thread of thin, invisible steel running up through my body has kept me going through some dark nights.

Thank you again for sharing this part of you with us.

Great piece. Really reminds me of some of the, for lack of a better term, body expression work of Petra Kuppers.

(Pedantic ed. note: “Cooler than me” is correct; “Cooler than I” is incorrect in standard American English.)

Carrie and Autostraddle, this was a terrific read. But it’s unfortunate that you neither alt-tagged nor captioned the picture of your tattoo for screenreader users, given that ir’s the centerpiece of the article. Lots of blind people have tattoos for similar reasons; please don’t reinforce the message that our bodies are okay to ignore.

This part: “That’s what ableism looks like filtered through privilege: an invitation to distance.” is so spot on in every way, and i’ve just never heard it articulated so clearly. Many thanks from this long time gimp upstart.

fun fact! i have not only tattooed like, my entire body covering scars, but did my (art therapy) grad school thesis on tattoos.

During my search for information on pain relief and minimizing spasticity during a tattoo for people with CP, I came across this article and I’m glad I read it. Very well done.