feature image via Manifesta Magazine.

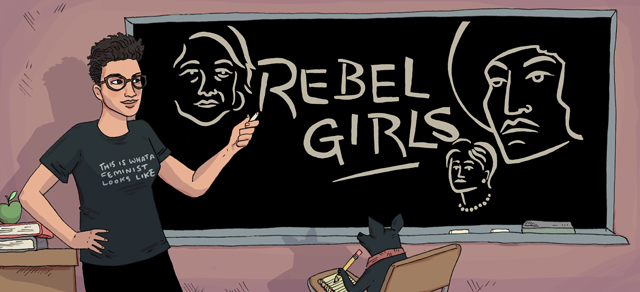

Header by Rory Midhani

Our lessons on privilege and oppression (this is part one, this is part two) might be helpful to glimpse over before / after / alongside your reading of this here post on intersectionality because it’s about how those, um, intersect! Isn’t that exciting! You’ve got so much to learn.

The term “intersectionality” is thrown around a lot these days, but I’m not sure if we’re all tapping into its actual power. The concept of intersectionality is so incredibly big, so Earth-shattering, so real and true and important. It’s about dismantling the movement and putting it back together again. It’s about rebuilding spaces so that they’re big enough for all of us and all of who we are.

In today’s lesson, I want to provide y’all with a quick historical overview of where intersectionality theory comes from — as well as a breakdown of what it demands of us as feminists.

The (Quick) History of the Term

The term intersectionality theory was famously coined by Black feminist scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw.

In a 1989 article, Crenshaw argued that Black women’s experiences were informed by not only their race or gender, but by both all the time. She argued famously that it wasn’t possible for Black women to pinpoint whether their race or gender were the root of any of their experiences, and that instead those two components of their identities interacted with each other.

Although Crenshaw claimed the term, and has gone on to speak extensively about how movements across issues can come to truly adopt and understand it, her work was an outgrowth of the writings and activism of Black feminist thought before her. The Combahee River Collective addressed “interlocking oppressi0ns” and “simultaneity” in their work, and Crenshaw herself locates its roots as far back as the 19th century and the works of Maria Stewart and Anna J. Cooper.

These ideas harken back to the matrices of power we discussed in this lesson, although intersectionality is both an individual and cultural phenomena. We all have intersecting identities and oppressions and privileges playing into our experiences and identities — but intersectionality doesn’t just address those individually complex identities. It also sets a foundation for cultural change in which people see other people as more nuanced and complex, and less defined by just one aspect of their experience. And in that way, intersectionality theory also demands more of feminism and other social movements based around components of identity. It demands that we carve out bigger spaces and make room for broader experiences, and that we stand in solidarity with people in our community who have different experiences than we do.

We have all likely felt the impact of siloed identities. Before the introduction of intersectionality theory, activists and academics alike interpreted the world and the experiences of people in it through very tiny lenses. There were Black experiences, female experiences, queer experiences. But for folks who belonged to all of those groups, for example, there was something else: the queer Black female experience. That meant that people who weren’t just Black, or just female, or just queer felt alien in every movement that was supposedly supposed to serve them.

This is something many of us still experience: being queer and a person of color can mean people feel out of place in both the LGBT rights movement and spaces for communities of color; women who are gay might feel excluded from feminist discourse as well as dominant gay discourse. Before intersectionality theory, though, those divides were even greater — because before feminists and other social justice writers, thinkers, and activists began contemplating the overlapping components of their own identities, they failed largely to devise strategies and mechanisms for achieving equality and justice that encompassed more than one of anyone’s.

What Intersectional Feminism Looks Like

And thus, we’ve arrived at the dawn of a new era in feminism: one in which intersectionality theory is part of the bread-and-butter of our movement. This isn’t to say that our movement no longer grapples with issues of race, class, gender, ability, sex, class, or any other categorization. It’s just to acknowledge that newer — and, often, the more prominent — voices in the movement put a priority of harnessing an intersectional lens, and applying intersectional theory to their work. For those of us who came of age in the movement in the nineties or later, we may not have even recognized that theory at work. It’s a relative privilege to have grown into a movement that had already begun tackling issues of difference and division — and it’s up to us to recognize how to finally eliminate and solve those once and for all.

Intersectionality theory will give us a stronger, better, faster feminist movement. One that is more united, more fierce, more all-encompassing, and more powerful than ever. And that’s because of what it stands for.

An End to Identity Silos

At its core, intersectionality is about recognizing the sum of our parts, and how different aspects of our identity inform our experience. These can be things we inherit from our being born into communities — of color, of queer people, of women — or things we acquire or have more control over, like education and class status. We cannot parse out the pieces of who we are and intersectionality theory demands a world in which we never have to. Honoring an end to those identity silos forces us not only to expand our understanding of the experiences of people in our own communities, but also to recognize how our experiences overlap with those of people who may not be in our communities at all.

For example, intersectionality theory reminds us that Black women cannot separate their blackness from their womanhood. Honoring their experiences as both part of the Black experience and the experiences of women broadens our ideas of what those communities face, and then connects them.

A New Vocabulary, A New Visualization

True intersectionality requires a new language. It gives us new names. It redefined the feminist movement. A movement that, historically, was concerned only with male supremacy and ending sexism has become a movement fighting for equality in a much broader sense. Intersectional feminism is about fighting for more than “women’s liberation.” It’s about fighting for an end to colonialism, racism, homophobia, transphobia, classism, poverty, ableism and all of the other social forces that hold people back and keep people down. And that’s because intersectionality tells us that no woman is free until all women are free, and no women can be free until all of the societal forces that oppress them are destroyed.

For differently-abled women, a feminism that doesn’t address ableism is bullshit. Ending sexism doesn’t create equality for them. For trans women, a feminism that doesn’t address transphobia and especially transmisogyny is bullshit. Ending sexism doesn’t create equality for them.

If feminism wants to liberate all women, it needs to fuck up a lot more than male dominance. It needs to rebuild the entire world.

Self-Examination and Purposeful Inclusion

Intersectionality also requires that we examine our own experiences. It demands that we be aware of how privilege informs our worldview. Truly intersectional feminism is about locating ourselves in the kyriarchy and recognizing how our privileges and our marginalization feed into each other and live alongside one another. And doing so also forces us not to center our experiences, not to build an entire movement around our unique places in the world — because examining our own relative privilege should remind us that privilege and oppression are complex, and manifest differently across identities.

That point at which we stop centering our experiences is the point at which truly intersectional work begins to happen, most notably through purposeful inclusion. Intersectionality theory questions how any movement can successfully liberate those who live at the intersections of oppression. Our answer to that question has to be to build a more inclusive, all-encompassing movement that seeks to do so.

Bottom-Up Politics

But what intersectionality ultimately demands of us — no, what it compels us to do — is examine our own privilege, observe the interlocking experiences of other people, and do the best we can to serve not only those in our position, but those who are even more marginalized and oppressed. The true manifestation of intersectionality is bottom-up politics, in which the needs and experiences of the most marginalized members of any given community are prioritized — and in which other members of the community recognize that doing so lifts them up as well.

All oppression is connected, even our own. All privilege is, too. Intersectionality theory reminds us all that until we are truly liberated — until all of the pieces of our identities are honored and respected — we will never be free. I’m a queer woman of color with a working-class background. I will not be free until all women are free, until all people of color are free, until all poor people are free, until all queer people are free.

Our liberation is tied to the liberation of people who are both like us and unlike us. That’s what intersectionality reminds us of, and that’s why it’s had such an impact on bringing different social justice movements together and creating spaces for people who live at the intersections of oppression. And only when we advocate for policies and social changes that tackle the experiences of those who face the most marginalization and oppression will we find ourselves identifying solutions to inequity and injustice that truly change the world — for everyone.

Readings and Resources for This Unit

- “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics.” Kimberle Crenshaw, 1989.

- How to Practice Intersectional Feminism Every Day, by Franchesca Ramsey and Laci Green (VIDEO)

- “Intersectionality 101.” Olena Hankivsky, The Institute for Intersectionality Research & Policy, SFU. 2014.

Rebel Girls is a column about women’s studies, the feminist movement, and the historical intersections of both of them. It’s kind of like taking a class, but better – because you don’t have to wear pants. To contact your professor privately, email carmen at autostraddle dot com. Ask questions about the lesson in the comments!

I love this so much.thank you!!

my pleasure <3

This is so useful! Thank you!

It has been a long time since I read Crenshaw’s work in college and it is nice to get an accessible, high-quality reminder on what this is all aobut. Thanks for this & for the further reading/resources suggestions!

This is perfect–and perfectly timed! Just had a conversation about this this morning and I’m so glad to have this information here as a refresher and resource.

Flavia Dzodan deserves a hat tip for originating “my feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit.”

a million hat tips, that is.

Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza deserves a hat tip for creating and defining kyriarchy (1992).

Thank you so much for writing this!

Thank you. <3

In an article aiming to define, praise, and encourage greater intersectionality in feminism, I find a glaring omission in that it ignores speciesism as one of the biggest oppressive ideologies that feminist, queer, and antiracist activists need to integrate into our work. While this was a great read, I have to take the opportunity to share a concern that has come up for me so many times on this website.

The ways that sex, sexuality, racism, poverty, misogyny, and animal exploitation overlap and support each other have been clearly documented and argued for (Carol J. Adams’ Sexual Politics of Meat is a good primer), but taking this fact seriously has been conspicuously absent from mainstream feminist discourse. The dairy industry in particular relies on the constant and near-exclusive exploitation of female bodies for (primarily white, straight, male) profit. The industry itself embraces its own misogynist degradation by using terms like “rape racks” to describe the confining apparatus used to forcibly impregnate cows for the ninth, tenth, thirteenth time.

How much evidence is enough to convince my fellow queer radicals that we simply MUST expand our *INTERSECTIONAL* fight for justice to include nonhuman animals? Women, animals, and female animals are caught in the mutually reinforcing cycles of violence that rely on and were systematically devised by patriarchal systems that devalue the feminine and the “other.” I know many people feel that it’s “too much” to include in their personal fight for justice or “not the same” and “not as pressing” as the deeply important and supremely valid social justice movements that this article highlights as being so intertwined. I just have to ask anyone who calls themselves a feminist to really search themselves and see if they can make room for the truth of nonhuman animal exploitation in their hearts and realize that their freedom is just as tied to our own. Research the ways animals are abused and why, the scale at which it occurs, who suffers from resultant environmental degradation, standard labor practices and the targeting of vulnerable populations, and see if it is really in line with your values.

Likewise, vegan and animal rights activists need to drastically improve our own practice of intersectionality. The key to intersectional practice to me lies in allied movements for justice recognizing their stake in each other’s work. It means not actively detracting from an ally’s work– not employing sexist or fat phobic campaigns for animal rights, not letting white feminism speak louder than anyone else in the room, and not promoting animal exploitation in queer fashion or food culture. It means listening and learning from queer vegans of color who are smashing down siloed identity myths and doing incredible, magical work for universal liberation.

It’s like an old, lazy arrow in my back every time I see a food post featuring dead animals that have been systemically abused on a QUEER, FEMINIST website. It’s incongruous, it’s unwelcoming, and it’s sure as hell not intersectional.

Not looking for a fight here at all, and I appreciate the ways that Autostraddle has improved its coverage of and relationship to intersectional issues that they sometimes struggled with. But the lack of awareness surrounding the very allied struggle of animal liberation has kept me from connecting with the site, and that’s sad. I’m just putting my queer vegan femme witch voice out there to let you know that there are members of this community that are asking for more from you, and from the larger queer community. I hope that there are others who see the same discontinuity here and that we are able to speak up as allies for justice for ALL beings, knowing that you are another myself and all our struggles are inextricably linked.

Thanks for listening <3

My first comment ever on this site and I 100 percent agree with you.

I think the National Lawyers Guild is an example of a radical, activist org that has taken real steps towards including animal exploitation among the social ills it’s fighting against.

See here:

https://www.nlg.org/news/announcements/nlg-food-justice-guidelines

Thank you for making this your inaugural comment! Those food justice guidelines are a perfect model for intersectional activism. A++++ thank you for sharing. #queerveganpower

Interested in reading more about this, but I’ve heard that Carol Adams is a product of her times and that (particularly her early writing) is a bit terfy. Any more recent reading recs that avoid that?

Defiant Daughters is a 2013 anthology that extends and diversifies Adams’ original thesis that the exploitation of women and animals buttress each other in myriad ways. I especially recommend Jasmin Singer’s chapter, where she describes the painful connection she made between the dairy industry’s rape racks and her own sexual assault. (Witnessing her personal truth in that essay was one of the last catalysts for me moving from vegetarian to vegan). I can also recommend Sistah Vegan as another great anthology of personal essays by vegans of color. It brings up all kinds of intersectional goodness to munch on from women of all ages. I would add that reading anything about the reality of animal agriculture will likely bring up other feminist and anti-racist connections that are personal to you. The best book I can recommend for the current state of animal exploitation is Eating Animals by Jonathan Safran Foer. There is unfortunately still a dearth of literature on intersectional veganism, but I hope this is helpful!

My writing is on autostraddle! Well sort of – I made the intersectionality banner used in the featured image. It’s from an Occupy camp in Nottingham, UK in 2012.

oh this is a fucking amazing turn of events!

\o/

Nice article!

What Intersectional Feminism Looks Like

stupid

next.

Carmen, I’m using a quote from this article for my sign at the march.

I love everything you write. You are extremely intelligent. And i hope one day you run for something. I will vote for you.