0. 1/28/2012 – Art Attack Call for Submissions, by Riese

1. 2/1/2012 – Art Attack Gallery: 100 Queer Woman Artists In Your Face, by The Team

2. 2/3/2012 – Judy Chicago, by Lindsay

3. 2/7/2012 – Gran Fury, by Rachel

4. 2/7/2012 – Diane Arbus, by MJ

5. 2/8/2012 – Laurel Nakadate, by Lemon

6. 2/9/2012 – 10 Websites For Looking At Pictures All Day, by Riese

7. 2/10/2012 – LTTR, by Jessica G.

8. 2/13/2012 – Hide/Seek, by Danielle

9. 2/15/2012 – Spotlight: Simone Meltesen, by Laneia

10. 2/15/2012 – Ivana, by Crystal

11. 2/15/2012 – Gluck, by Jennifer Thompson

12. 2/16/2012 – Jean-Michel Basquiat, by Gabrielle

13. 2/20/2012 – Yoko Ono, by Carmen

14. 2/20/2012 – Zanele Muholi, by Jamie

15. 2/20/2012 – The Malaya Project, by Whitney

16. 2/21/2012 – Feminist Fan Tees, by Ani Iti

17. 2/22/2012 – 12 Great Movies About Art, by Riese

18. 2/22/2012 – Kara Walker, by Liz

19. 2/22/2012 – Dese’Rae L. Stage, by Laneia

20. 2/22/2012 – Maya Deren, by Celia David

21. 2/22/2012 – Spotlight: Bex Freund, by Rachel

22. 2/24/2012 – All the Cunning Stunts, by Krista Burton

23. 2/26/2012 – An Introductory Guide to Comics for Ladygays, by Ash

24. 2/27/2012 – Jenny Holzer, by Kolleen

25. 2/27/2012 – Tamara de Lempicka by Amanda Catharine

25. 2/27/2012 – 10 Contemporary Lesbian Photographers You Should Know About, by Lemon/Carrie/Riese

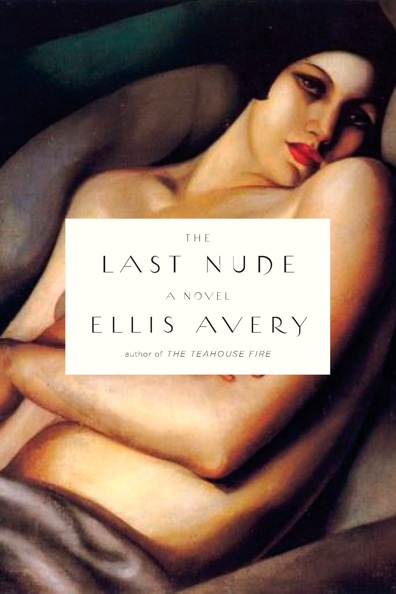

26. 2/27/2012 – Read a F*cking Book: ‘The Last Nude,’ by Amanda Catharine

![]()

How do you write a novel about a real person? How do you decide what to keep or dismiss, embellish or invent? The challenge is compounded when there are still people alive to remember the subject — when those who were there, or whose parents were there, are in a position to maintain the official story or offer their own inevitable fictions? After all, unlike the biographer, the novelist doesn’t need to parse the legend created by her subject. In fact, she’s at liberty to pick and choose the most interesting, titillating, or salacious aspects and expand on them at will, all under the safe umbrella of fiction. Ellis Avery approaches such a legend in her book The Last Nude, which centers on the painter Tamara de Lempicka, perhaps best known for iconic, frequently reproduced paintings: “Auto Portrait” and “La Belle Rafaela.” (Read Art Attack!: Tamara de Lempicka Didn’t Care Who Knew)

I’m always hesitant to read historical fiction about real people because, while I love the genre, I can’t help but wonder if what I’m reading is true. I’m distracted by the intersection of fact and fiction and, if I’m perfectly honest, I usually wind up reading a biography after the novel. Avery elegantly avoids this problem – for I suspect there are a lot of would-be detectives like me! – by structuring her narrative in two parts. The first, comprising the bulk of the book, recounts the events of just under a year in the life of Rafaela, the model for de Lempicka’s famous painting. In giving Rafaela a surname, Fano, and a voice, Avery brings to life the woman who has so long be known only by a face on a canvas that has enthralled, seduced; been studied and psychoanalyzed. Rafaela’s narration is vibrant and believable as a seventeen-year-old American making her way in Paris without, of course, the permission of her parents. Avery strikes the right balance between youthful naïveté and hardened woman of the world, which surviving in Paris has made her. Rafaela entertains dreams of becoming a designer in between entertaining the men whose money and gifts pay for her apartment until her association with de Lempicka affords her a paycheck and independence.

Throughout Rafaela’s portion we meet several of the Parisian literati of the time, including Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier, who cameo as Rafaela’s helpful lesbian godmothers. The minor characters flit around Rafaela and Tamara in varying degrees of complexity, and some prior knowledge of the characters – Romaine Brooks, Natalie Barney, etc. – is helpful, but not necessary. They stand alone as characters, but those interested in early 20th century LGBT culture will appreciate seeing them brought to life.

Rafaela’s idea of romance, tarnished by a string of boyfriends who certainly weren’t there for love, is rekindled when she meets a beautifully appointed woman perched on a car at the Bois de Boulogne. The woman is Tamara de Lempicka, and for this first part of the book, we see Tamara through Rafaela’s eyes, colored as they are by admiration, seduction, and a tragic inability to see Tamara’s betrayal until it blindsides her. Tamara is at first an apparition of elegance and aristocratic manner, but as the story progresses, the reader readily perceives cracks in the façade: where Rafaela falls in love with Tamara, it’s apparent from the first page that Tamara is more in love with the idea of Rafaela than she could ever be with the girl herself. Nevertheless, Tamara takes Rafaela home to her apartment to model, and ultimately to her bed. Their love affair is masterfully woven with the story of Tamara’s painting, the sweetness and passion of it all rendered with a literary echo of the sensual brushstrokes and vibrant color that characterizes the real “Belle Rafaela.”

There’s likely a temptation to fictionalize real people into characters who bear but a passing resemblance to their models so as to tell a better story, to make them more saintly or more horrific according to the plot. Tamara de Lempicka, to be sure, led a life that didn’t require much embellishment to seduce and enthrall the reader. If anything, Avery needed to humanize her, to dissociate her however minutely from the wealth, the jet-setting, the marriages, the fabulous parties and scandalous affairs, to turn her into a person worth caring about – which is not the same thing as caring about or respecting her artwork. Rafaela – who is wholly fictional, since not much is known about the model – is drawn to Tamara first by her accoutrements, before she knows anything about her: by her fancy car, her exclusive address, exotic profession, even the crispness of her gloves.

The last sixty pages are narrated in Tamara’s voice as an old woman. The device makes for a poetic but rushed ending as Avery must use Tamara to make up the time between the end of Rafaela’s story and Tamara’s old age. Avery is a writer of great subtlety, and it is particularly evident in the last few pages as Tamara considers the Rafaela she first painted and the ones she has worked on since, using artwork, appropriately, as a lens to examine aging. But it’s a one-sided and ultimately unsatisfying ending that is full of lovely phrases but unfulfilling in terms of the plot.

The Last Nude, like Avery’s first novel, The Teahouse Fire, is a deliciously ambiguous novel in its assessment of the characters, appropriate for a book that deals with real people who can’t be neatly pigeonholed for an ending. Rafaela may be the one betrayed, but she’s far from an innocent angel, and while Tamara is ruthless in her pursuit of art, money, and patronage, she’s ultimately not an unconscionable manipulator. It’s a story about the confluence of love and art, of sensual romance and pure eroticism, but also about the realities of life, particularly one lived at a time when one’s opportunities were limited by gender, money, and language – not so different, then, from our own.

And in the end, it’s a measured consideration of what kind of people might have provided the context in which to create art: the interpersonal relationships that foster the creativity behind it, the city that grounds it, the exchange of money and services that facilitate it, and what the people involved in its creation are obligated to sacrifice for its sake. The Last Nude provides a compellingly written backstory for a woman whose arresting, penetrating stare has captivated art aficionados for years. Ultimately, it’s still fiction peppered with appearances from well-known figures – but I rather like thinking of Rafaela as more than a footnote to the title of a painting.

for some reason i have never been interested in paintings/painters… until now.

i would read the hell out of this book.

My dad who sells books for a living got me an advanced readers copy and I was skeptical at first since I don’t give a fruit about art, but really enjoyed the book. http://lucyhallowell.blogspot.com/2012/01/booked.html